Chapter 3

Sharing the Education Revolution

The Colombo Plan

Our formal education relationship began under Australia's Colombo Plan for Cooperative Economic Development in South and South East Asia. The Colombo Plan, as it became known, was established in 1951 as a cooperative venture for the economic and social advancement of people in the South and Southeast Asian regions. The venture included a program to sponsor students from the Commonwealth nations—later expanded to include 27 countries—to study in Australia. The newly-independent Federation of Malaya became a member in 1957 at a time of structural reorganisation of its own education system.

Local education authorities were being established, boards and management frameworks put in place, and teacher training programs were being developed across the country. Malaya was also making the transition from a British curriculum to one that instilled the Malay language and literacy and fostered 'a common Malayan outlook'.3 The tertiary sector was modest. The University of Malaya, incorporating the former Raffles College and King Edward VII College of Medicine, had been established in 1949. At independence this institution, together with the Technical College in Kuala Lumpur and the Serdang Agricultural College, made up Malaya's tertiary sector.

While Malaya's membership of the Colombo Plan marked the beginning of our formal education relationship in 1957, Australia was by then already an educational destination of choice for Malayan students. Like Australia, postwar Malaya was hungry for higher education and the Federation of Malaya's first Annual Report acknowledges that it 'is interesting to note the increasing tendency of students from Malaya to seek both university and the equivalent of VI Form education in Australia'.4 The 1957 report records that 1669 Malayan students were studying at overseas universities and colleges, half of whom had chosen Australia. Of these, 699 were privately funded and only 160 were Colombo Plan students.5 There were also 673 privately funded Malayan students at Australian technical colleges at this time. Recent research, however, highlights that the assistance of Colombo Plan scholarships in fact confirmed Australia's educational credentials, as recognition of the benefits of a Colombo Plan education in Australia to its recipients spread and 'opened the 6 and to a vibrant education industry.

Today, Malaysians no longer study in Australia under the Colombo Plan but many undertake postgraduate study and research with the assistance of the Australian Government's prestigious Endeavour Scholarships. In 2015, 17 high-achieving Malaysian graduates won Endeavour Awards, including the Endeavour Vocational Education and Training Scholarship, Endeavour Research Fellowship, Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship (Masters), Endeavour Executive Fellowships, and the Endeavour Australia Cheung Kong Research Fellowship. Also available are the Australia–Malaysia 'Towards 2020' Executive Awards for civil servants to undertake professional development in Australia, plus a Research Fellowship in Australia.

Fair Dinkum Malaysians

In Australia, the postwar educational revolution saw the demand for tertiary education soar. In 1946, adding to the six established 'sandstone universities',7 the Australian National University (ANU) was opened, followed by the New South Wales University of Technology in 1949 and University of New England in 1954. By 1967, six more Australian universities had been established8 and, by then, Malaysian and Australian tertiary education was firmly intertwined.

Students from Malaysia were part of life across Australia's mushrooming university campuses. In 1953, Samuel (Sam) Abraham, a Colombo Plan scholar from Kuala Lumpur studying medicine at the University of Adelaide, became the first Asian student to be elected President of the Student Representative Council at an Australian university.9 Malaysian students lodged with Australian families and worked during term holidays in post offices and department stores, or picked fruit in the country to earn 'that extra pocket money', The Straits Times reported.10

The cultural transition was not always easy, but as a Malaysian medical student wrote in one of the first editions of Monash University's student newspaper, Lot's Wife, in 1964, the 'Fair Dinkum Asian'

… not only gain[s] the benefits of an education, but also acquire[s] a clearer insight into the Australian way of life, and cultivate[s] friendship and good will which they can cherish and propagate for the rest of their lives.11

Many not only cultivated friendships, they found their life partners as a result of their Australian education. Professor Jamilah Ariffin, now Adjunct Professor in Global Health at Monash University, met her husband as a Colombo Plan student in Australia. And among Malaya's first Colombo Plan cohort was Hijjas Kasturi, now one of Malaysia's most celebrated architects. In 1971, Hijjas met his future wife, a young Australian in Kuala Lumpur with the Australian Volunteers Abroad program and, as we see later in Chapter 4, they have since built an inspiring artist's exchange program between their two countries.

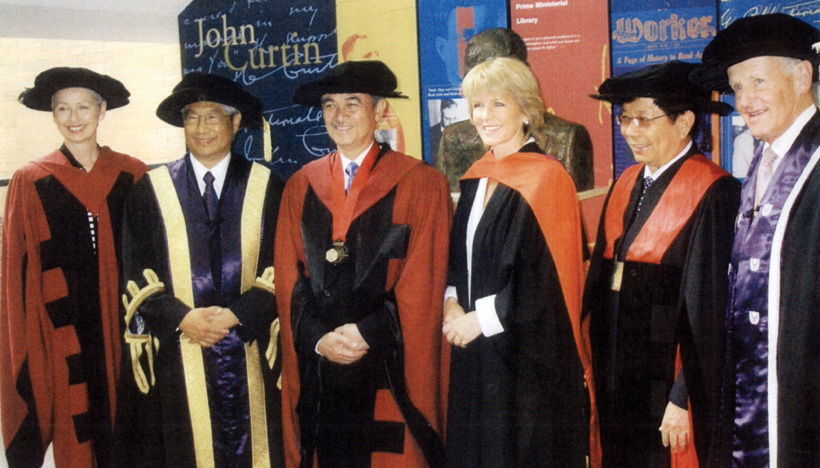

Malaysian Prime Minister, Tun Abdullah Badawi (third from left), was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Technology at Curtin University of Technology, Perth, 22 February 2006.

From left: Professor Jeanette Hacket, Deputy Vice- Chancellor; Eric Tan, former Chancellor; Julie Bishop, Australian Minister for Education, Science and Training; Datuk Patinggy Tan Sri Dr George Chan Hong Nam, Deputy Chief Minister of Sarawak; and Professor Lance Twomey, Vice-Chancellor.

Others such as Malaysia's Trade Minister Dato' Sri Mustapa Mohamed, who graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1974 with a first class Honours degree in Economics, have gone on to successful political careers. Australian universities in turn have recognised the contribution of Malaysian leaders. Dato' Sri Mustapa was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Commerce in 1997, with former Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi accepting an Honorary Doctorate from Curtin University in 2006 and Prime Minister Najib Razak receiving an Honorary Doctorate from Monash University in 2011. In celebrating the success of postwar Malaysian students, however, we should not forget the success of earlier students who sought further education in Australia. For example, Tun Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman—Malaysia's Deputy Prime Minister (1970–73)—who, in 1945, was the first Malaysian to graduate with a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) from the University of Melbourne.

My Story

Reminiscing about my years as a Colombo Plan scholar at La Trobe University, Melbourne, prompts funny, poignant, sad and even exhilarating memories.

Initially, I wanted to study at the University of Malaya where I could continue to play my favourite sport, hockey. But my elder siblings told me it would be unwise not to accept this golden opportunity to go overseas on a prestigious scholarship and then return to serve in the Malaysian Civil Service. So, reluctantly, I agreed to go to Australia.

Consequently, in March 1968, dressed in a proper Western suit and carrying a smart woollen coat, I boarded a small Fokker F27 Friendship and left behind my teary parents and several friends. In Melbourne we were whisked away to an etiquette class at the Victorian Department of Education and Science, to be schooled in the intricacies of Australian culture. We were aware that we were to become 'young ambassadors' of our country.

At La Trobe University in Bundoora, we were introduced to the earlier batch of Malaysian Colombo Plan students—the founding group, one of whom was Abdul Ghani Othman, my future husband! At a reunion with my former university mates of La Trobe University in December 2014, I found out that the Australian boys had been intrigued by this Asian girl with her flowing sarong kebaya, and they imagined she was a right royal Asian princess!

The first months of my new life in Australia were a tough adjustment, and while alone in my college room, I felt so desolate and could actually hear 'the sound of silence'. However, I am always grateful that the Australian Master of Glen College, Mr. Meredith, the kind and motherly college maid, Mrs. Smith, as well as the staff and all my Australian university mates and students, were always so hospitable, friendly and helpful towards me. Hence, even now, I have a very positive opinion of Australians and Australia.

Charting the way for Malaysians 'down under'

In 1976, 3139 private Malaysian students were in post-secondary and higher education in Australia and this more than doubled, to over 7000, in the next decade.12 In 1975, the Malaysian Government recognised the growth in demand for an Australian education and purchased a motel in Sydney for student accommodation. The following year, in May 1976, Malaysia Hall was opened by then High Commissioner Tun Dr Awang Hassan. This was followed by Malaysia Halls in Melbourne and Perth. Far from the sometimes apprehensive students of the 1950s and 1960s, Malaysians are today one of the most organised groups of international students in Australia, with student associations across 23 Australian university campuses, all of which are affiliated with a national body, the Malaysian Students' Council of Australia (MASCA).13 MASCA's motto 'Charting the way for Malaysians Down Under' manifests in a highly organised program of activities, including the Malaysian Summit of Australia, the Australian Network Leaders Summit, the Down Under Camp, and the Majlis Perwakilan Pelajar Luar Negara (MPPLN) Public Policy event which, with the support of the Malaysian Government, encourages debate on public policy in Malaysia.14

The Australia–Malaysia Institute (AMI) and MASCA also developed a strong interactive relationship which has centred around ensuring that Malaysian students not only enjoy their education while in Australia, but have opportunities to interact socially with Australians and to participate in the cultural and sporting activities that feature in Australian life. The Malaysian Student Council of Sydney also holds an annual Malaysian Festival—known as MFest—and 2015 marks its twenty-ninth year. In 2014, 28 000 Sydneysiders participated in MFest activities, which include music, dance, theatre and, of course, food. MFest organisers noted that 47 per cent of these visitors were Malaysians. That the remaining 53 per cent came from beyond the Malaysian community highlights the extent to which the Australia–Malaysia education relationship represents so much more than a mere transaction for education services.15

My Story

Chairperson MASCA Victoria (2014-15)

It all began in July 2013 during winter. I flew all the way from Kuala Lumpur to Melbourne on an eight hour journey. Heavy gushes of rain and blistering wind welcomed us upon our arrival. A sea of umbrellas was a familiar sight back then. It was pretty cold and gloomy.

Long story short, now I have been here for three years. Just like other aspiring students, I'm here to complete my undergraduate studies, a Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology to be exact. God willing, by mid-2016, I'm going to graduate from The University of Melbourne with hopefully a deserving scroll of honour.

Being a Malaysian student studying in Australia, I learnt to step out of my comfort zone. I still remember the moment I volunteered to be the host for orientation week in the university. It was an exciting yet a challenging responsibility to help a group of new students to discover the hidden gems of the prestigious institution. We had fun getting to know each other while at the same time preparing ourselves for university life. As the circle was comprised of different nationalities, I have come to realise the importance of embracing diversity–a significant similarity of celebrating the multicultural diversity that I love between Australia and Malaysia.

And this experience was only a snippet moment of my life here. I am humbled enough to travel around, to be a part of a student organisation and learning the history of this land both formally and informally. I believe there is a lot more knowledge to be sought, endless experiences to be gained and infinite adventures to be embarked on. And I am more grateful than ever to be in the land Down Under. With the hope of spreading love, I look forward to a more fulfilling journey ahead.