Introduction

Australia's relationship with Malaysia is a long and significant one. Even before 1955, when an Australian Commission was established in Kuala Lumpur, relations had grown around regional and bilateral trading networks, shared experiences of war, and people-to-people contacts. From the nineteenth century, Australians were involved in the economy of the Malay states and in the twentieth century tin and rubber were particularly important to Australia's economic and industrial development. In the post-war era, Malaya became a key Southeast Asian ally for Australia, central to its strategic planning in the region.1 Today Malaysia sits among Australia's top ten trading partners and it ranks second among Australia's trade with the 10 ASEAN nations.2 Our two nations share many common interests, in our parliamentary, legal and administrative systems and in the networks of multilateral cooperation that bind us in our region.

As our trade and security relationship has progressed, our friendship has deepened through connections between our people fostered by education, migration, tourism, business, sport and the arts. Our educational relationship is enduring, beginning with the Colombo Plan in the 1950s. It was reported in 1956 that of the 309 Colombo Plan students sitting for a Bachelor's degree in Australia, 'the most successful national group was Malayan, with a 93 per cent pass rate'.3 Now, on average, over 20 000 Malaysian students enrol to study in Australia each year, with another 20 000 studying on an Australian university campus in Malaysia.4 In 2015, we further demonstrated our joint commitment to education with the launch in Malaysia of the New Colombo Plan.

The tourism sector has also contributed significantly to our networks of people-to-people contact. In 1975, 28 270 Australians travelled to Malaysia, a number that increased tenfold over the next four decades to 571 328 in 2014.5 The number of Malaysians visiting Australia has increased even more significantly. In 1975, 9568 Malaysian visitors came to Australia; in 2014 this had swelled to 324 500.6 Over six decades Australians' familiarity with Malaysia has become more personal. For many, for example, the Sandakan Memorial Park in Sabah, where 2400 Australian and British prisoners of war died during the Pacific War, has become a site of pilgrimage on Anzac Day and Sandakan Memorial Day.

Well before the Commonwealth of Australia and the Federation of Malaysia were imagined, however, our people had been coming into contact. Four centuries ago, in 1606, the Spanish explorer, Luis Vaez de Torres, sighted Malay boats traversing the Gulf of Carpentaria. Possibly these carried early trepang fisherman from the eastern Indo-Malaysian Archipelago who were recorded in the 18th century as living and trading with Indigenous Australians.7 Today, imprints of the Malay language on Indigenous languages remain in Australia's far north.8 In the 19th century, Malays became part of Australia's burgeoning pearling industry, which attracted workers from across the region. By 1900, before Japanese pearl divers came to dominate the industry, Malay divers were the majority group, with almost 500 living and working in and around Broome.9

These contacts provide only a glimpse into the early foundations laid for today's Australia– Malaysia relationship. Other links were quietly forged in the colonial era and more recently, as the stories in this book will reveal, there have been many individual contributions to both countries' future prosperity and friendship. One example is the early association between George Town in Penang and Adelaide in South Australia, which led to a Sister City link being formalised in 1973. Well over a century earlier, Colonel William Light, the son of Captain Francis Light—who acquired Penang on behalf of the British East India Company in 1786—founded the city of Adelaide in 1836 as its Surveyor General.10 Adelaide has continued to feature as home to some of Australia's best known Malaysian–Australians—such as recording artist Kamahl and Australian Idol winner and Eurovision entrant Guy Sebastian, celebrity chefs Adam Liaw and Poh Ling Yeow, and Labor Senator for South Australia Penny Wong—and the Sister City heritage ties remain strong.

Commemorating 60 years of Australia's diplomatic presence in Kuala Lumpur returns us to the 1950s, a tumultuous decade for Southeast Asia. Much of the region decoupled from its colonial past in the immediate post-war years and as it did so, new alliances—and non-alliances—were formed. In September 1954, the South East Asia Treaty Organisation was formalised and, little more than six months later, in April 1955, the Asian– African Conference at Bandung in Indonesia signalled the birth of the Non-Aligned Movement. While the first Indochina War in Vietnam had come to its unresolved settlement, Communist insurgencies elsewhere in Southeast Asia continued to undermine stability in the region.

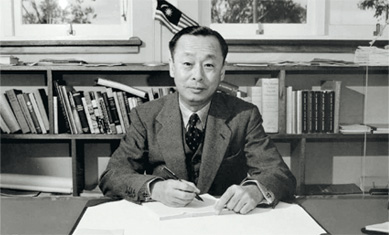

In November 1955, Australia's Minister for External Affairs Richard Casey declared that 'it was now appropriate and desirable for Australia to have a full-time Australian Representative at Kuala Lumpur' where constitutional developments were carrying the Federation of Malaya towards selfgovernment.11 Two months earlier, HM (Max) Loveday had been sent to Kuala Lumpur as Assistant Commissioner to the Australian Commissioner to Southeast Asia based in Singapore. Following Casey's statement, TK (Tom) Critchley was appointed as Australia's first Commissioner in Malaya, a post he took up on 7 December 1955.

Malaya, in turn, established its first Commission in Canberra on 20 November 1956. The first Commissioner was Dato' Nik Kamil Mahmood12 who was followed in August 1957 by Dato' Gunn Lay Teik,13 who remained in Canberra until May 1960. The Commissions in Kuala Lumpur and Canberra became High Commissions when the Federation of Malaya formally became independent on 31 August 1957.

Australia's relations with Malaya were close during these formative years, not least due to their shared outlook as members of the Commonwealth. In 1957, also, Sir William McKell, a former Governor-General of Australia, together with four other Commonwealth jurists, was involved in the Reid Commission that helped draft the Constitution of the Federation of Malaya. In the same year, Australia successfully sponsored Malaya's membership of the United Nations, granted on 17 September 1957. Four years later, in 1961, as the United Kingdom sought to decolonise the last of its Southeast Asian territories, negotiations began on a proposal to incorporate the Federation of Malaya, the Crown Colony of Singapore, and the North Borneo territories of Sabah (British North Borneo) and Sarawak into a wider federation. Australia supported the proposal, believing it offered the best chance for peace and stability in the region, and committed to seeking regional and international backing for the new federation. On 16 September 1963, the Federation of Malaysia was born. Australia continued to be a staunch friend to the new nation. Indonesia objected to the new arrangement and between 1963 and 1965 tensions were high between the two neighbours, prompting Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies to pledge Australian military assistance to defend Malaysia's territorial integrity and sovereignty.

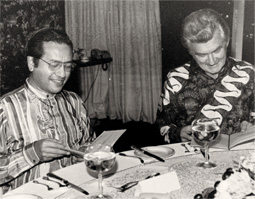

High Commissioner Tom Critchley, who represented Australia's interests in Malaya and Malaysia through this turbulent period, remains Australia's longest serving diplomatic representative to Malaysia, and his decade in Kuala Lumpur was one of personal warmth in the relationship. In August 1962, when Critchley was married at his home in Kuala Lumpur, guests included the Yang di-Pertuan Agong Tuanku Syed Harun Putra KCMG, the Sultan of Selangor, the Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak and several Cabinet Ministers.14 When the Critchleys' daughter was born in December 1964, she was named Karen Laurie, so her initials would be KL.15

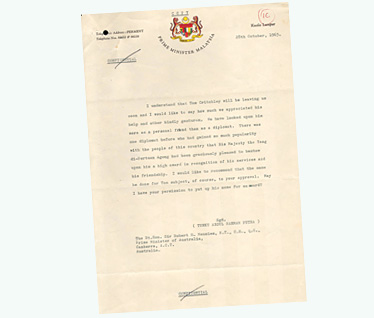

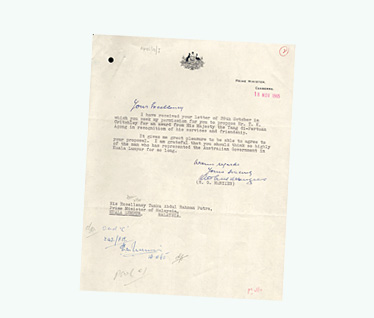

Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman regarded the High Commissioner 'more as a personal friend than a diplomat' to Malaya. The Tunku sought approval to bestow a title from the Yang di-Pertuan Agong upon Critchley 'in recognition of his services and his friendship'.16 Menzies replied that it would give him 'great pleasure to be able to agree' to the proposal,17 and so Dato' Tom Critchley became the first, and only, Australian diplomat to receive this honour. In The Straits Times, echoing the Tunku's recognition that friendship was the hallmark of the Australia–Malaysia relationship during his tenure, Dato' Critchley reflected, 'I have made many goodfriends' and he felt sure those friendships would endure.18 His departure was marked by 'an enormous two-day golf and feasting party'.19

This was also a time of major stresses and strains in international relations due to the superpower rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States. Maintaining security and stability in the region was a prime focus for both countries and the Australia–Malaya partnership worked closely together towards achieving this goal. As early as 1949, Australia, Britain and New Zealand had reached an agreement, known as ANZAM—Australia, New Zealand and Malaya—which provided for Commonwealth defence planning in the region. Australia played a pivotal role in ANZAM and, in 1955, its deployment of forces from all three services to the Malaya–Singapore region represented its first overseas military commitment in peacetime.20 Further defence measures were then put in place under the Anglo-Malayan Defence Agreement (AMDA) in 1957, which allowed for British troops to remain in Malaya after independence. Malaysia's first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman suggested Australian and New Zealand observers be invited to attend AMDA meetings and in April 1959, they both signed agreements formalising their AMDA membership.21 The AMDA and ANZAM agreements made way for the still current Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) between Australia, Britain, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore drawn up after Britain formally withdrew all its military capability east of Suez in 1971.

The British withdrawal signalled a shift, though not a diminution of importance, in Australia–Malaysia relations. During the 1960s and 1970s Malaysia focused increasingly on building regional linkages. In 1967, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand joined to form ASEAN. In 1971, it declared Southeast Asia a Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality. At that time, Malaysia also joined the Non-Aligned Movement. Australia welcomed the formation of the ASEAN regional grouping. Indeed, in the early 1960s External Affairs Minister Sir Garfield Barwick had seen the importance of a process of regional Southeast Asian dialogue22 and this sentiment has endured. In 1974, Australia became ASEAN's first Dialogue Partner.23

In the past 40 years Australia and Malaysia have deepened cooperation in the region through shared membership of key arrangements. Both have been at the forefront of some of these regional developments. In 1989, inspired by ideas of 'open regionalism', the Hawke Government initiated the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).24 In 2005, under the Abdullah Badawi Government, the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the East Asia Summit brought the East Asia Summit into being and it is now considered the key forum in the Asia–Pacific. Australia and Malaysia also share membership of the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meetings Plus and the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Australia's economic engagement with Malaya has also been evident from the 1950s. In 1956, about 10 per cent of Australia's Colombo Plan budget went to Malaya, and this increased to around 30 per cent in 1970.25 Our trade relationship was also formalised in the early years of diplomatic relations. In 1958, under the Menzies Government, Australia and Malaya signed their first trade agreement—the first such commitment by Australia in Southeast Asia—and this was revised by the Whitlam Government in 1974 to provide for greater flexibility on tariffs.26 Trade, across six decades, has continued in a steady upward trajectory. A bilateral Malaysia–Australia Free Trade Agreement (MAFTA) was signed in May 2012 and came into force in January 2013. This built on the plurilateral ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA), which came into effect in 2010, more deeply committing Australia and Malaysia to regional trade and investment.

Our investment partnership has grown more gradually but has nevertheless increased over the past few decades. In 1990, Malaysia–Australia two-way investment accounted for only 1 per cent of Australia's two-way investment relationships in Asia. This placed it behind Australia's investment relationships with all the major Asian economies. By 2012, however, this situation had improved considerably, and our two-way investment stood at 8 per cent of Australian investment in Asia.27 Between 2010 and 2013, two way investment more than doubled, to A$26 billion in 2013.28 It remained steady at that rate into 2014, and investment momentum is developing in several key areas.29

Over the 60 years since the establishment of a diplomatic presence in Kuala Lumpur, the Australia–Malaysia partnership has gone from strength to strength. When it was established in 2005, marking 50 years of relations, the Australia–Malaysia Institute (AMI) set its mission:

The AMI, together with a range of organisations, including the Malaysia–Australia Business Council (MABC) established in 1986 and the Australia– Malaysia Business Council (AMBC)—formed in 1987 to promote trade, investment, economic cooperation and tourism between the two countries—have helped make the Australia–Malaysia partnership a bilateral success story. It is remarkable to review what we have achieved since 1955.

In honour of this 60-year milestone, this publication returns to key moments in our relationship, reviews the progress we have made and the friendships that have formed, and considers the future for Australia–Malaysia relations. Across four chapters we focus on the principal areas of engagement—our history, political relations, defence and security ties, and trade and investment. We then look at the dynamic education ties, from the Colombo Plan of the 1950s, '60s and '70s, to the New Colombo Plan of the twenty-first century, that have added intellectual capital to our relationship, and cemented people-to-people connections. Finally, we delve further into those connections by looking at immigration, tourism, the arts and sport.

As we will discover, the richness of the relations that have evolved over six decades justifies optimism that we will share an equally dynamic future.

1959

1974

1977

1984

1996

2005

2008

2011

2014

2015