Evaluation of Australia's response to the Horn of Africa humanitarian crisis, 2011

2.1 The 2011 Horn of Africa crisis

The 2011 Horn of Africa (HoA) crisis had devastating effects on Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya. Its impact was greatest in Somalia, where the catastrophic combination of drought and conflict took place against a backdrop of progressive deterioration in environmental and social conditions.

The crisis grew in the very heartland of modern international humanitarian action, around its oldest and most intense operational hubÂNairobi. Since the 1970s, humanitarian, political and military operations have responded to a succession of conflicts, droughts, famines and refugee crises across the HoA. The humanitarian community is probably more entrenched in this region than in any other part of the world. This density of humanitarian capacity across the region explains why the crisis in Ethiopia and Kenya was so effectively managed in most areas. Paradoxically, it may also explain why the tragic famine that took shape in Somalia was initially so hard to see amid the conflict, chronic uncertainty and remote management that has characterised humanitarian action in Somalia for many years.

The HoA crisis was not the only major international crisis in 2011Â12. The Libya crisis was in full swingÂinternational military intervention started in March 2011. The Syrian uprising also began in March 2011 and quickly deteriorated into civil war. More widely, the 'Arab spring' started in December 2010 and was continuing around the Middle East and North Africa. All these events demanded political, humanitarian and media attention that competed with the HoA crisis. However, in 2011, no other event would result in as many deaths as the HoA crisis.

2.2 Entrenched ecological and livelihood vulnerability

The HoA has a long history of drought and increasing livelihood vulnerability resulting in long-term aid dependency. From 2010, specific global weather effects (La Niña) resulted in a number of poor and intermittent rains.2,3 This weather effect severely impacted on livelihoods, particularly in pastoral areas and the delicate riverine agricultural area of south-central Somalia.

People in the affected areas have a mix of livelihoods including pastoralist, agro-pastoralist and farming. Pastoralist livelihoods had been under threat before the crisis, with increasing inequalities emerging within pastoralist groups. Some pastoralists adapted well, increasing their market linkages and trade with the Middle East. These pastoralist 'winners' stood in marked contrast to an increasing number of pastoralist 'drop-outs', forced out of a pastoralist livelihood by repeated shocks in recent years, and other pastoralist 'losers' who were just clinging on.4 Gender and socioeconomic inequality are also entrenched across the region. This mix of factors required any humanitarian response to be highly sensitive to the different livelihoods, coping mechanisms and vulnerabilities.a

When the crisis began, the international humanitarian community had developed a strong understanding of vulnerability and need in the region's sedentary agricultural populations, largely through the household food economy model pioneered in the 1990s.5 This knowledge and practice was generally widespread through the humanitarian system in the region and championed by mega-agencies like the United Nations (UN) World Food Programme (WFP) and UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Understanding of pastoralist livelihoods was largely confined to a niche group of international and local experts who had a sophisticated knowledge of pastoralist economies, adaptation and coping strategies. There were also strong ideas about what constituted timely and constructive aid to pastoralists.6 Several pastoralist experts were lobbying for increased and improved humanitarian response to pastoralist communities throughout 2011Â12. This knowledge was not common across the humanitarian sector and had no champion in a mega-agency or major donor that would lead large-scale innovative aid for pastoralist people. Much livelihood degradation could have been prevented by better and larger pastoralist programming.

2.3 Conflict and instability

Political control of the Somali state has been violently contested for decades. Political Islam emerged to play a major role in Somalia's conflict through the Islamic courts movement in the early 2000s and subsequently through Al-Shabaab and several other Islamist groups. Al-Shabaab is primarily a national movement, seeking to impose strict Sharia law and remove foreign influence. The movement has links to Al Qaeda,b which has given the conflict a strong 'war-on-terror' dynamic since 2001. Support for the Somali Transitional Federal Government (2007Â12) and Federal Government of Somalia (since 2012) in the conflict with Al-Shabaab has come from the United Nations (UN) Security Council and the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), the multicounty African union force. Endorsed and resourced by the UN, AMISOM also receives significant support from the United States, United Kingdom and European Union. These donors also invest considerable bilateral resources in attempts to limit Al-Shabaab.

Throughout the crisis, and the critical years beforehand, AMISOM and Al-Shabaab were in conflict. This made international aid organisations fearful of being militarily targeted by Al-Shabaab or prosecuted in the United States.7 Sanction strategies were pursued by both sides. Al-Shabaab took strong measures to limit the number of 'western' aid agencies entering their territory, regarding them as potential spies. Aid agencies withdrew from parts of Somalia because of security threats and being banned by Al-Shabaab. Sanctions were implemented by the United States Government's Office for Foreign Assets Control and the UN Security Council to stop Al-Shabaab gaining resources and increasing their political control. While an important element of counterterrorism activities and efforts to halt Al-Shabaab, the sanctions had a negative impact on food supply. The amount of food aid provided by the United States in 2011 was about one-tenth of that provided in 2009.

2.4 The need for humanitarian assistance

The crisis is rightly seen as a regional one, born of profound long-term livelihood vulnerability for millions of people and entrenched regional conflict. Conflicts within the region meant that an effective regional response was not possible and the need for humanitarian assistance was massive.

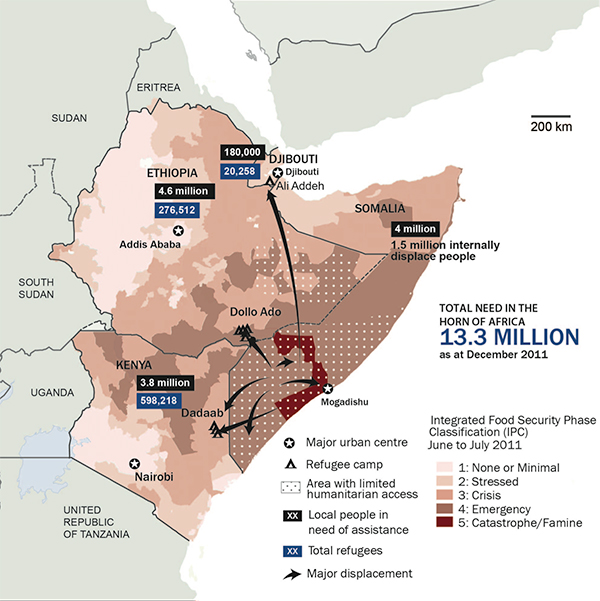

The level of humanitarian need was continually revised upwards as the crisis unfolded throughout 2011. The estimate grew to 13.3 million people in need of assistance across the region (Figure 1). Of the 4 million people in need of assistance in Somalia, 2.8 million were in the south. The epicentre of the crisis was the riverine areas of south-central Somalia, where the famine killed an estimated 257 500 people, about half of whom were under five years old.8

New arrivals making their way to the refugee camps in Dadaab, Kenya, August 2011. Photo: Katie Drew, Save the Children

As the famine worsened, there was large-scale movement of people fleeing the worst-affected areas of Somalia. Some 167 000 people became displaced around Mogadishu. Many Somalis sought asylum in neighbouring Ethiopia and Kenya. In Ethiopia, the crisis resulted in 4.6 million local people as well as 276 500 Somali refugees in need of assistance. In Kenya it was estimated that there were 3.8 million local people, plus 598 000 Somali refugees in need of assistance.

Food was clearly a priority area for humanitarian assistance but the severity of the crisis meant that affected people needed multiple forms of assistance. Water, shelter, protection, livelihood support and cash were all needed. Water shortages (for people and livestock) became extreme in the Somali region of Ethiopia, parts of northern Kenya and Somalia itself. As food prices rose and food aid access was blocked in Somalia, cash became an urgent priority (Box 1). Protection needs were high in Somalia, both for those in the worst-affected areas and for the large groups of displaced people, which were predominantly made up of women and children, who were forced to travelled long distances in search of assistance.

Figure 1 Food insecurity and numbers of people in need of assistance in the Horn of Africa, 2011

Source: Adapted from OCHA/FEWS NET East Africa: Drought Snapshots form July and December, 2011.

Note: The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is a measure of how bad food insecurity is. It uses a set of standard tools to classify the severity of food insecurity into five phases. The phases are determined from a broad range of measures which includes food consumption, livelihoods changes, nutritional status, and mortality. Context-specific and other factors such as food availability, vulnerability and hazards are also taken into account. The IPCs shown on the map are for July 2011 when mortality rates were highest. The numbers of people who needed assistance and refugees are from December 2011.

2.6 The context of humanitarian operations in Somalia

The nature and quality of existing humanitarian capacity in the region played a critical role in how the crisis was managed. Capacity differed between the three countries concerned, with capacity being very limited in Somalia.c In 2011, Somalia had no effective central government. What governance there was tended to be clan led, based on the limited reach of the Somalia Transitional Federal Government around Mogadishu or very strong control by Al-Shabaab and foreign jihadist fighters in their territories. Security concerns and inaccessibility made delivery of humanitarian assistance in Somalia extremely challenging.

As a result of security threats, the humanitarian response in the famine epicentre was mostly remotely managed. Humanitarian operations in Somalia rely on subcontracting implementation to local NGOs and business people, some of whom are former UN and NGO staff members. This informal network negotiates and delivers humanitarian aid on behalf of distant donors with little direct monitoring. Humanitarian operations in the crisis were led from Nairobi with occasional visits to meet implementing partners in Mogadishu, usually in the airport. This network is remarkable yet vulnerable. The situation was different in the Somali border regions of Puntland and Somaliland, where some direct management was possible.

Humanitarian operations in the worst-affected areas of Somalia were impaired by the inability of agencies to secure consistent access. In the lead up to and during the crisis, many humanitarian agencies, including the UN WFP, were expelled by Al-Shabaab from territories under its control. Eventually Al-Shabaab bans affected 22 aid agencies.

Aid agencies that did have access in Al-ShabaabÂcontrolled areas were subjected to a system of 'regulation, taxation and surveillance'.9 In late 2009, Al-Shabaab imposed 11 conditions on aid agencies in south-central Somalia, 'including payments of registration and security fees, the removal of all logos from agency vehicles and a ban on female employees'. The traditional approach of providing the bulk of assistance as food, shelter materials and other in-kind aid is always problematic in conflict-affected and highly insecure countries such as Somalia. Conditions imposed by Al-Shabaab made operations extremely difficult. Al-Shabaab tried to control the delivery of aid and in some cases insisted that 'food distributions be carried out directly by Al-Shabaab officials or their proxies'.10 This led humanitarian agencies to explore innovative and more efficient ways of delivering aid.

One such approach was the use of cash transfers (see Box 1). Cash transfers had been used in Somalia for many years before the 2011 crisis as a way to circumvent access and security challenges. At the time of the crisis, the use of cash transfers was highly politicised and there were concerns about security and corruption risks, including fear of diversion to Al-Shabaab or foreign jihadist fighters. Even though these concerns made some agencies reluctant to use cash transfers, other agencies felt that the conditions in Somalia were appropriate for the use of cash transfers. The 2011 HoA crisis was, at the time, the largest ever delivery of cash transfers, with more than US$100 million in cash provided to beneficiaries in Somalia.

Conclusion

- The HoA crisis took place in an incredibly difficult political and operational context, and this should be considered when attempting to evaluate outcomes.

Box 1 Cash-transfer programming

Providing cash relief in emergencies has a long history. Cash programming is usually delivered either through direct cash grants or by giving vouchers. It can be provided with or without conditions.11 Cash-transfer programming is increasingly used as an alternative to in-kind humanitarian aid (such as food, shelter, medicine, household items). A good practice review by the Overseas Development Institute points out that cash transfers are 'simply an instrument that can be usedÂwhen appropriateÂto meet particular objectives in particular contexts and sectors of response'.12

The advantages of cash transfers include:

- They offer freedom of choice for beneficiaries as they can choose the commodities they want to consume.

- They are generally less visible, have lower operational costs and are quicker to deploy than in-kind assistance.

- If markets are already functioning, cash transfers can stimulate markets rather than inflate prices.13

The possible disadvantages of cash transfers include:

- They may be used to pay off debts, rather than purchase commodities.

- Inflation of prices may occur when supply of food and items in markets is low. In these circumstances, food aid is more appropriate than cash.

- The implementation may take some time as aid agencies need to set up the delivery process if it is not already in place before a disaster.

- Delivery mechanisms require proof of identity to receive cash, which many poor and vulnerable people may not have or be able to obtain.

In humanitarian situations, cash transfers are usually unconditional and are typically used by beneficiaries to address food security and nutrition issues.14 The proven success of cash transfers in some contexts has led United Nations (UN) agencies to expand their use of cash transfers and vouchers. In 2010, the UN World Food Programme targeted 4.2 million beneficiaries with 35 programs valued at $140 million. Other UN agencies that had significant experience in the use of cash transfers at the time of the crisis included the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the United Nations Children's Fund, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. The challenge for UN agencies, non-government organisations, donors and governments is to determine when cash transfers are the most effective form of assistance.

Footnotes

a For an excellent distillation of evidence-based good practice in such emergencies, see Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action, Humanitarian action in drought-related emergencies, lessons paper, Overseas Development Institute, London, 2011.

b The Australian Government listed Al-Shabaab as a terrorist organisation on 22 August 2009 and 18 August 2012. The Government has noted the link between Al-Shabaab and Al Qaeda, as confirmed by both organisations in a public announcement on 9 February 2012, see: www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/Listedterroristorganisations/Pages/Al-Shabaab.aspx.

c For an overview of regional humanitarian response, see H Slim, IASC real-time evaluation of the humanitarian response to the Horn of Africa drought crisis in Somalia, Ethiopia and KenyaÂsynthesis report, UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee, Geneva, 2012.

References

2 FEWS NET, Executive brief: La Niña and food security in East Africa, August 2010, Famine Early Warning System Network, Washington, 2010.

3 Assessment Capacities Project, Overview of early warning information on FS in East Africa (August 2010ÂJune 2011), www.acaps.org/img/documents/annex-1---early-warning-and-information-systems-in-east-africa-acaps---annex-1---early-warning-and-information-systems-in-east-africa.pdf, 2011.

4 Regional Pastoral Livelihoods Advocacy Project, Pastoralism, demographics, settlement and service provision in the Horn of Africa: transformation and opportunities, Overseas Development Institute, London, 2010.

5 See, for instance, T Boudreau, The Food Economy Approach: a framework for understanding rural livelihoods. Relief and Rehabilitation Network, London, 1998.

6 S Levine, A Crosskey & M Abdinoor, System failure: revisiting the problems of timely response to crises in the Horn of Africa, HPN Paper 72, Overseas Development Institute, London, 2011.

7 J Darcy, P Bonard & S Dini, IASC real-time evaluation of the humanitarian response to the Horn of Africa drought crisis, Somalia 2011Â12, Inter-Agency Standing Committee and Valid International, Geneva, 2012.

8 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine & John Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2013.

9 A Jackson & A Aynte, Al-Shabaab engagement with aid agencies, Policy Brief 53, Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute, London, 2013.

10 A Jackson & A Aynte, 2013.

11 S Bailey & P Harvey, Cash transfer programming in emergencies, Good Practice Review, Humanitarian Practice Network at Overseas Development Institute, United Kingdom, 2011.

12 S Bailey & P Harvey, 2011.

13 Grosh, de Ninno, Tesliuc and Ouerghi, The design and implementation of effective safety nets: for protection and promotion, World Bank, Washington DC, 2008.

14 S Bailey & P Harvey, 2011.