A Joint Australia–China Report on Strengthening Investment and Technological Cooperation in Agriculture to Enhance Food Security

Imprint information

ISBN 978-1-74322-042-9 (print)

ISBN 978-1-74322-043-6 (PDF format)

ISBN 978-1-74322-045-0 (online)

Contact

Inquiries regarding the report are welcome at:

Assistant Secretary

East Asia Branch

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

R G Casey Building

John McEwen Crescent

Barton ACT 0221 Australia

Phone: +61 2 6261 1111

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author: Australia. Dept. of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Title: Feeding the future : a joint Australia–China study on strengthening agricultural investment and technological cooperation to improve food security / Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

(Australia) and Ministry of Commerce (China).

ISBN: 9781743220429 (pbk.)

Subjects: Agriculture–Australia.

Agriculture–China.

Food security–Australia.

Food security–China.

Food industry and trade–Australia.

Food industry and trade–China.

Corporations, Foreign–Australia.

Corporations, Foreign–China.

Photographs copyright © Commonwealth of Australia

Joint Ministerial Foreword

It is a pleasure to present this joint study between Australia and China on how to strengthen investment and technological cooperation in agriculture to enhance food security. We–Australia's Ministers for Trade and Competitiveness and for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and China's Ministers of Commerce and of Agriculture–began discussing this important global issue last year.

Continuing population growth and limited land and water resources, particularly in the Asia–Pacific region, have made food security a priority for many governments. As the economies in our region grow, and per capita incomes rise, consumers will increasingly demand safe, high-quality, high-protein food.

Australia has earned a global reputation for its expertise in agriculture and the high quality of its produce. It still has large tracts of unused or under-utilised areas in its northern regions. Some of this land could, with investment in new productive capacity and the appropriate application of technologies, produce more food for sale on world markets.

China has its own expertise in agriculture as well as a surplus of investible capital, and has developed great plans for the further development of modern agriculture. After decades of progress and growth, China has developed advanced agricultural technology in areas such as crop breeding; plant disease and insect pest prevention and control technologies; and animal disease prevention and control. Firms also spread these leading technologies internationally, and so make an important contribution to improving food production and enhancing global food security.

In our discussions, we agreed that our two countries could work together to ease growing pressure on global food supplies. In the follow-up, Australia hosted two delegations of Chinese government, business and banking representatives in the agricultural sector. A reciprocal visit to China by Australian business representatives and officials provided further input to the study.

This paper is, first and foremost, about cooperation to raise rural productivity to supply global markets. By bringing land, capital and know-how together our two countries can make a difference. Additionally, both countries hope to develop technological cooperation and investment opportunities to improve the production of agrifood.

At the same time, we recognise that this study makes a limited contribution to the challenge of global food security. But it helps to establish a best-practice approach to Australia–China cooperation on this issue, which could provide a model for improved international cooperation. The principles it identifies are central to long-term success in our bilateral cooperation on agribusiness. Governments need to provide the right policy and regulatory environment so that companies can make sound decisions.

Strengthening agricultural investment and deepening technological cooperation is a focus of international cooperation to address food security, and is also an important measure to promote bilateral cooperation. This is the first time that our two governments have worked together on such a project. It is an excellent example of what can be achieved through cooperation, a model we may wish to emulate in the future. We sincerely thank all those who have contributed to this report.

Craig Emerson

Minister for Trade and Competitiveness

Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on Asian Century Policy

Australia

Joe Ludwig

Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

Australia

Chen Deming

Minister of Commerce

People's Republic of China

Han Changfu

Minister of Agriculture

People's Republic of China

Contents

- Joint Ministerial Foreword

- Glossary

- Technical notes

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- List of figures and maps

- Executive Summary

- Recommendations

- Chapter 1: Overview

- Chapter 2: Agriculture in Australia and China

- Chapter 3: Investment and technological cooperation in agriculture

- Chapter 4: Challenges in Australia–China investment and technological cooperation in agriculture

- Chapter 5: Priorities for Australia–China investment and technological cooperation in agriculture

- Chapter 6: Conclusions and recommendations to ministers

- Statistical annex

- Appendix 1: Official visits associated with the joint study

- Appendix 2: Websites

- Appendix 3: China's foreign investment policy for the agricultural sector

- Appendix 4: Australian Policy Statement: Foreign Investment in Agriculture

- Acknowledgements

- References

Glossary

- agrifood

- In this report, "agrifood" is defined as any food or beverage, or food or beverage material from unprocessed through semi-processed to fully processed (e.g. from wheat grain through flour to bread, biscuits and pasta); and this includes fish and seafood products; it does not include inedible agricultural materials and products like fibre (e.g. wool, cotton and hides) or forestry products.

- food security

- There are many concepts and definitions of food security, the most widely accepted internationally is that developed by the 191 member states of the Food and Agriculture Organization: "Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life" (FAO, 2009a). Each country has its own detailed perspective on food security. In China, food security means all people, at all times, have access to affordable basic foodstuffs. In this definition, basic foodstuffs refers to the most important grains for maintaining human existence. The internationally accepted definition of food covers grains and other agricultural products including meats, vegetables, fruits and aquatic products. Australia's perspective is that most countries will produce some part of their nation's food supplies; but that it is important for countries to recognise that maximising one's national food security will usually mean the most efficient mix of domestic food production, exports and imports.

- grains

- The Chinese definition of grains includes cereals, legumes and tubers. In most countries, including Australia, grains generally refers only to cereals.

- ha

- Hectare; equivalent to 15 mu.

- mu

- Chinese unit of area measurement; equivalent to 1/15 of a hectare, or 667 square metres.

Technical notes

Unless otherwise specified, all value data are in Australian dollars.

Unless otherwise specified, all data are for calendar years.

Some data are only available for Australian financial years, which run from 1 July to 30 June.

Where applicable, the following conversion rates have been used:

| Year | Australian dollar (AUD) -> US dollars (USD) | Australian dollar (AUD) -> Chinese Yuan (CNY) |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 0.8525 | 5.9303 |

| 2009 | 0.7927 | 5.4148 |

| 2010 | 0.9197 | 6.2224 |

| 2011 | 1.0320 | 6.6696 |

| 2012 | 1.0343 | 6.5495 |

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Note that the 2012 figure is the average for the period 1 January–31 August.

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- ABARES

- Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences

- ABS

- Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ACACA

- Australia–China Agricultural Cooperation Agreement

- ACBC

- Australia–China Business Council

- ACIAR

- Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research

- ACSRF

- Australia–China Science and Research Fund

- ANZ

- Australian and New Zealand Banking Corporation

- AusAID

- Australian Agency for International Development

- Austrade

- Australian Trade Commission

- CAS

- Chinese Academy of Sciences

- CSIRO

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

- DAFF

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

- DFAT

- Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- DIISTRE

- Australian Government Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education

- FAO

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- FDI

- foreign direct investment

- FIRB

- Australian Foreign Investment Review Board

- JAC

- Australia–China Joint Agricultural Commission

- JMEC

- Australia–China Joint Ministerial Economic Commission

- MOA

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China

- MOFCOM

- Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China

- NFF

- National Farmers' Federation

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

- PMSEIC

- Australian Prime Minister's Science, Engineering and Innovation Council

- PRC

- People's Republic of China

- R&D

- research and development

- RIRDC

- Australian Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation

- UN

- United Nations

- WTO

- World Trade Organization

List of figures and maps

- Figure 1

- Global arable land and grain yields, 1978–2010

- Figure 2

- China's agriculture value-added in GDP and its composition in 2010

- Figure 3

- China's grain production, 1978–2011

- Figure 4

- Australian agrifood exports by main category, 2001–11

- Figure 5

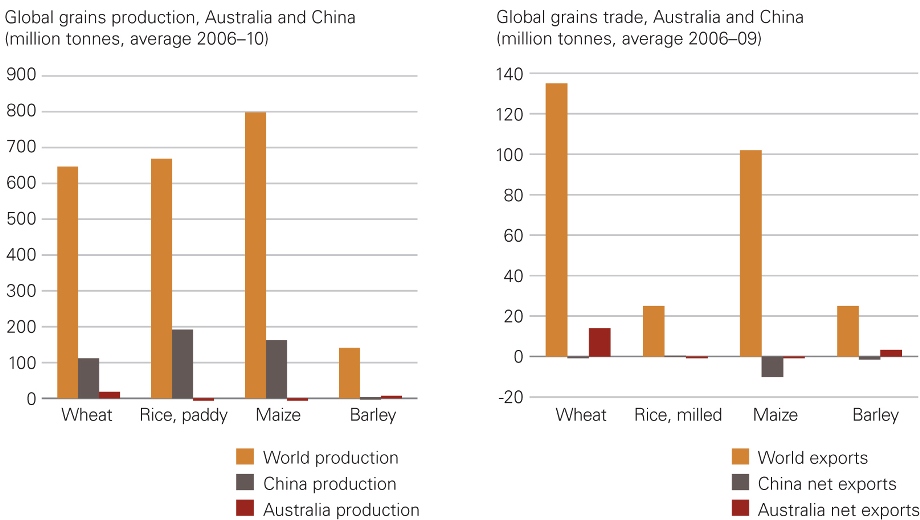

- Global grains production and trade–Australia's and China's shares

- Figure 6

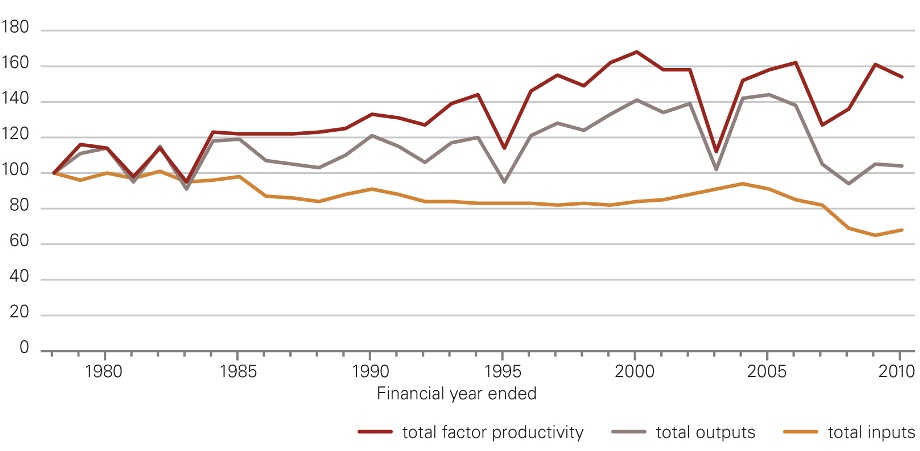

- Trends in Australian broadacre total factor productivity, total inputs and total outputs, 1977–78 to 2009–10

- Figure 7

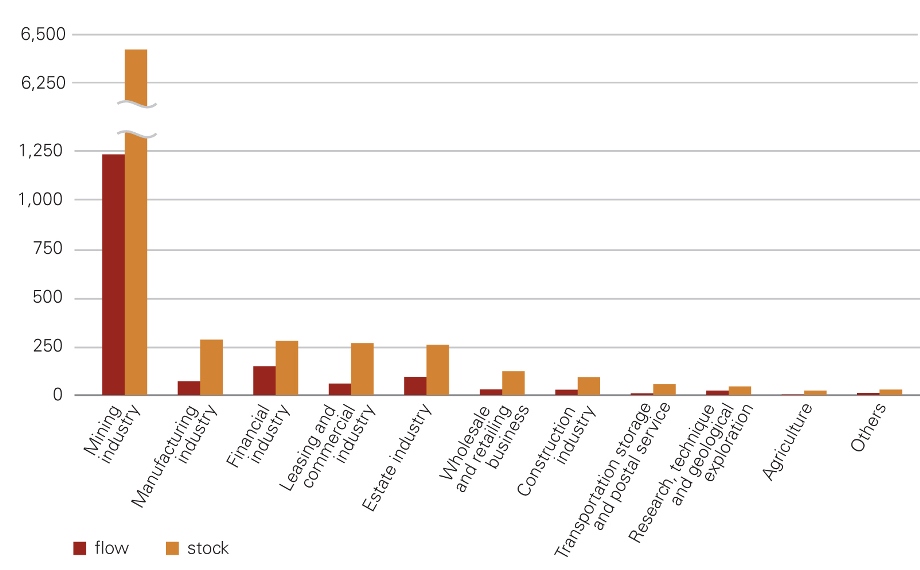

- Chinese direct investment in Australia by sector, 2010

- Figure 8

- Chinese foreign direct investment in agriculture, all countries, 2008–2011

- Figure 9

- Sectoral distribution of Chinese direct investment in Australian agriculture

- Map 1

- Land use in Australia, 2005–06

- Map 2

- Australia's average annual rainfall

- Map 3

- The Ord, Flinders and Gilbert Rivers of northern Australia

Executive Summary

Food security will remain a global concern for decades to come as demand increases and pressures grow on supply. Australia and China share a common interest in ensuring food security nationally, regionally and globally. Further cooperation between Australia and China can make a significant contribution to improving food security, as well as providing opportunities for commercial benefits to people who farm or fish and to agrifood businesses in both countries.

Australia and China are natural partners for collaboration. Both are major agricultural producers. Both face challenges to maintain and expand food production. Both are at the forefront of agricultural innovation, research and development. Both have expertise in sectors such as dryland agriculture that can be shared with other countries facing similar problems.

China is one of the world's largest producers of grains, most of which is consumed domestically. Improving productive capacity and achieving self-sufficiency of grains for a large population of 1.35 billion is one of the priorities for China's government. China faces challenges of limited water and land resources, and the increasing frequency of natural disasters associated with climate change. The Chinese Government has developed the 12th Five-Year Plan on National Agriculture and Rural Economic Development (2011–2015) to guide China's agricultural production and development. Foreign investment in agrifood is permitted under an approval system. There is a detailed catalogue which specifies the sectors in which investment is encouraged, permitted and, in some areas, restricted or prohibited (see Appendix 3).

Australia produces much less food than many other countries, including China, but is able to export well over half of its agrifood production. It is a leading supplier to world markets of beef, sheepmeat, wheat, barley, sugar and dairy products. Australia is expected to remain a substantial surplus producer but agricultural production faces challenges including limited land and water resources, adapting to climate change, the need for improved infrastructure and a slowing in the rate of productivity growth. A framework for the Australian Government's response is the forthcoming National Food Plan.

Australia welcomes foreign investment, including in the agrifood sector. Foreign capital has long supplemented domestic savings to help finance the development, improvement and operation of agricultural and food businesses–so making Australians more prosperous. Australia is an attractive destination for foreign investment because of the low level of sovereign risk. The Australian Government's 18 January 2012 "Policy Statement: Foreign Investment in Agriculture" (see Appendix 4) reaffirms the Australian Government's policy framework and provides detailed guidance specific to the sector. The Australian Government is taking steps to ensure the policy is well understood and to strengthen the transparency of foreign ownership of rural land and agrifood production.

Chinese investment in Australia's agrifood sector is in its infancy with investment projects small in number and size. But it is increasing and diversifying in scope, type of investor, mode of investment, and area of investment.

Australia's agrifood investment in China is even smaller. A small number of Australian firms have invested in China, primarily to help sell their products there. A number of firms are providing logistical and rural banking services.

Bilateral investment cooperation should focus on improving productivity and expanding productive capacity sustainably in both countries, with any increase in production in Australia available for sale on world markets. Areas with high potential include: developing water and soil resources in northern Australia; commercialising new technology and new plant and animal varieties; and improvements in food processing and logistics.

China's government has invested much effort and money in improving its level of agricultural and related technology, driven by the domestic demand for food. After decades of progress and growth, China has developed advanced agricultural technology in areas such as crop breeding, and prevention and control technologies for plant diseases, insect pests and animal diseases. It is starting to focus more on issues such as monitoring the environmental effects of food production, raising food safety standards and improving quality assurance systems.

Agricultural innovation has been a necessary response to Australia's particular climatic and environmental conditions. As a result, Australian governments have invested significantly in agricultural research and innovation. Australian researchers have a record of world-class scientific results in fields such as low-carbon farming, sustainable agriculture, genetic resources, and plant and animal health.

Australia and China have a history of productive cooperation in agricultural research and development. Much of this was funded initially by Australia's aid program. Cooperation between the two countries now is increasingly moving towards a commercial basis and is growing deeper.

While Chinese firms' investment in Australia's agrifood sector is growing, some perceive challenges including: risks in obtaining government approval; delayed returns on investment and risks of excessive "green tape"; labour shortages; and difficulties in obtaining all the necessary information. Chinese researchers and farmers also have concerns about the difficulty of achieving good results in China with imported technology, and the absence of an effective platform for technological exchange, cooperation and exhibition.

Some Australian firms also see challenges to investing in China, including: perceived risks associated with the policy environment and regulatory oversight; land ownership and security of tenure; the development of agribusiness logistics; the need for strengthened enforcement of food-quality regulations; and the market for transferring rural land-use rights. Australian researchers generally view collaboration with China favourably but perceive concerns about intellectual property rights; identifying suitable Chinese counterparts; and insufficient language and inter-cultural skills among some Australian researchers.

Notwithstanding these perceived challenges there are opportunities for mutually beneficial investment, especially where this will expand productive capacity. Chinese firms are interested in investing in new irrigation developments in northern Australia (such as the Ord-East Kimberley Expansion Project); in the raising and processing of animals and their output (such as dairy products); tropical agriculture; offshore mariculture; the commercialisation of agrifood-related research; and food processing. There are opportunities for Australian firms to provide specialised services such as distribution, logistics and supply-chain management, land remediation–a growing need in China–and rural banking. There are also opportunities for Australian researchers and firms to develop demonstration farms in China to showcase their expertise and accomplishments.

Furthermore, there are opportunities for cooperation in innovation and technology that can improve productivity and be commercialised. Priority areas include: sustainable agriculture; animal and plant genetic resources; animal disease health; plant biotechnology; agricultural processing; environmental remediation; and remote sensing technologies for agriculture.

Australia and China have concluded that cooperation in the agrifood sector can contribute to improving global food security. This can be achieved through investment that lifts productivity and expands productive capacity, and focused cooperation in innovation, technology and services. As this cooperation between Australia and China begins in earnest, the objective is to establish a best-practice approach based on these guiding principles:

- Australia and China see the development of long-term, mutually beneficial cooperation on agrifood for supply to world markets as an important next step in diversifying a high-quality, complementary economic relationship.

- Australia and China recognise the importance of developing long-term sustainable policy approaches by building cooperation in stages and at a pace suited to the particular national situations, institutions and relative economic advantages of both countries.

- Australia and China recognise the valuable role of joint commercialisation of agricultural technologies to ensure the uptake of food security-related innovation within a framework of protection and management of intellectual property.

- In Australia, the transparency of the scale and nature of investment intentions and a focus on developing large-scale projects on underdeveloped land, particularly in northern Australia, will be important in promoting public understanding of foreign investment in Australia and providing confidence to Chinese investors.

- The demonstration effect is a valuable tool in developing agribusiness, and so Australia and China should work to improve the coordination of agrifood-related research and development priorities between key research organisations.

- Both governments have an important role to play in improving investment certainty by supporting pilot projects and addressing regulatory concerns, but bilateral cooperation on agribusiness will only be successful in the long term if Australian and Chinese companies make sound commercial decisions.

- The initial geographic focus of investment cooperation will be, in Australia, northern Australia (Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory); and, in China, Shanghai Municipality, Shandong Province, Anhui Province and Shaanxi Province. However, cooperation will not be limited to these areas only.

- The initial focus of cooperative investment activities will be large-scale agricultural water and soil resources development in northern Australia; promotion and application of proprietary technologies and new varieties in agricultural product processing (including beef and sheepmeat); aquaculture (including tropical rock lobster farming); and building modern agricultural logistics systems.

- The initial focus of technological cooperation will be sustainable agriculture; plant genetic resources; plant biosecurity; animal disease control and health; plant biotechnology; agricultural processing technologies; animal genetic resources; environmental remediation; remote sensing technologies for agriculture; and supply-chain development and improvement.

Recommendations

(I) Investment

- Both countries should make relevant improvements in providing comprehensive information on the regulatory environment (including environment protection, land and water resource management, quarantine and food safety, tax policies and legal systems). This includes:

- tailoring the relevant government websites/portals to provide timely information on agribusiness investment opportunities, and detailed procedures on making investments in the two countries, including links to the relevant sections of state, territory and provincial websites of both countries as well as relevant regulators, industry associations and other important stakeholders.

- The Northern Australia Ministerial Forum should consider holding a joint meeting with counterpart Chinese provincial ministers to discuss and review initial results, and explore further opportunities for cooperation and investment.

- Both countries should support annual delegation visits by potential investors in both countries to learn from the results of cooperation on joint pilot projects and other activities in order to develop new investment opportunities.

- Both countries should encourage new entrants to the agribusiness markets to make use of the services provided by the Australia–China Business Council, the Australian National Farmers' Federation, the Australian Food and Grocery Council and equivalent Chinese business groups to assist them to understand better the requirements of good corporate citizenship.

- Australia's national, state and territory governments should strengthen cooperation to reduce regulatory duplication, particularly in environmental protection requirements as agreed by the Council of Australian Governments.

- The Australian Government should continue to make transparency in foreign investment in the agricultural sector a high priority, including through measures such as the refined and ongoing surveys by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the development of the national foreign ownership register for agricultural land announced by the Prime Minister on 23 October 2012.

- Prospective investors need first to consider the employment of suitably skilled Australian workers in new agricultural developments. If a sufficient number of suitably skilled Australian workers cannot be found, prospective investors should utilise existing migration arrangements to address any labour shortfall. The Australian Government will provide guidance on how the current policies can be used to achieve this outcome.

- Both countries should ensure quarantine and food safety systems are efficient and effective so that new–and existing–agriculture investors in Australia and China are able to sell their products in foreign markets.

- The Australian Government should identify, with relevant Australian state and territory governments, appropriate pilot projects to demonstrate the feasibility of joint development of irrigated broadacre cropping, including the feasibility of mosaic irrigation.

(II) Technological and services cooperation

- Australia and China should further clearly define the organisations undertaking technological cooperation and key research projects, and publish a joint audit of cooperative research in English and Chinese.

- Australia and China should explore the feasibility of establishing a joint research centre with a robust commercialisation capability in order to:

- fully explore the opportunities for commercialisation in the existing research cooperation between Australian and Chinese researchers;

- match capital, markets, technology and services;

- improve intellectual property protection; and

- coordinate dialogue on successful commercial adaptation of technology between Australian Government organisations such as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Commercialisation Australia and Austrade, and relevant Chinese counterparts.

- Australia and China should encourage the use of centres of excellence and demonstration projects in both Australia and China to showcase innovation, explore best-practice management and enhance prospects for commercialisation and licensing of technologies developed through those centres and projects.

- Australia and China should support annual business-focused technology and services delegation visits to learn from the results of cooperation on joint research projects and other activities in order to develop new joint commercialisation opportunities, and to explore opportunities for more effective delivery of services to enhance agrifood productivity, such as logistics and supply-chain management.

- Encourage Australian financial services providers to look at opportunities to expand their rural banking where this would strengthen investment and technological services in China.

- Australia and China should explore the possibility of holding a "China Day" at a future Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences conference.

(III) Joint consultative mechanisms

- Both countries should make maximum use of the existing economic, trade and agriculture official consultation mechanisms, including the Joint Ministerial Economic Commission and the Joint Agricultural Commission, to research and promote bilateral cooperation on food security, and hold regular high-level discussions about bilateral cooperation on food security

Chapter 1: Overview

I. Strengthening agricultural cooperation between Australia and China to deal with global food security challenges

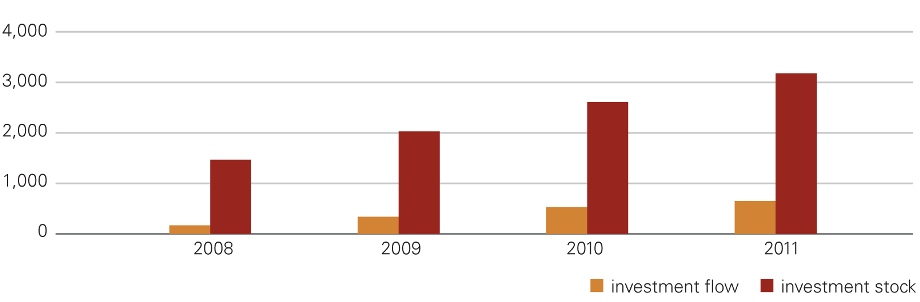

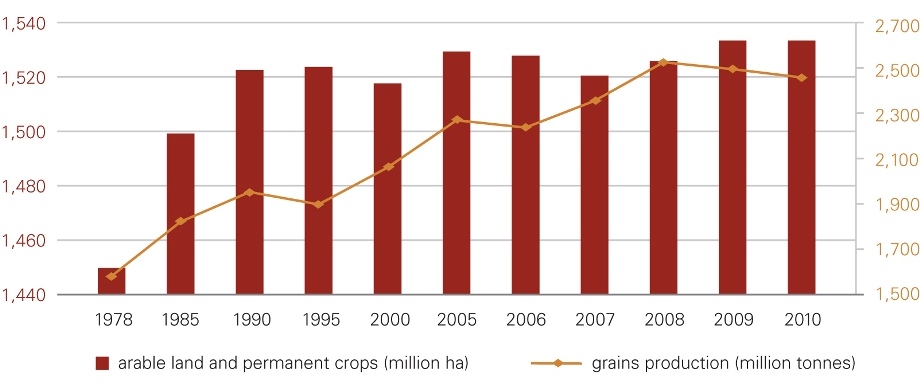

In the 21st century, with continuing global population growth and changes in food consumption patterns, the scale of global food demand will continue to grow significantly. However, the limited available arable land and water resources, and the slowdown in yield growth for grains are tightening the worldwide food supply and demand balance (see Figure 1). Since 2007, food prices and potential shortages, caused by a number of factors, have been of great concern among many countries. International attention has focused once again on global food security. According to World Bank statistics, 925 million people suffered from hunger in 2010.

Source: FAO database, November 2012

According to the Population Division of the United Nations, the world's population is projected to rise to 9.3 billion by 2050 from the current seven billion. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has estimated that global food demand will increase by around 70 per cent by 2050, and global grains demand could double from the current 2.5 billion tonnes by 2050. Food prices are expected to remain higher on average than pre-2006 levels for at least the coming decade. This will pose challenges for global food security. However, if markets work, higher prices can also act as incentives for farmers to produce more.

Food security is a complex and critical global issue, and there is much debate over its causes and solutions. Generally accepted causes include increasing consumption as a result of continued population growth, changing consumption patterns driven by rising incomes and accelerating urbanisation, and limited land and water resources. More controversially, some believe the continued effort to develop biofuels by the USA, European Union, Brazil and others has put strains on food production. Others have raised concerns about the possible contribution of financial speculation to the significant rise in agricultural commodity prices over the past half-decade, and the impact of severe price volatility on major agricultural commodity importers and exporters.

However, a study published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and FAO in May 2011 found that supply and demand remained the fundamental drivers of agricultural commodity prices, that speculation played an essential market role in providing liquidity to commodity trade, and that more open and extensive trade was a key way to reduce price volatility.

Improving food security is a major global challenge. Enhancing investment and technological cooperation in agriculture between Australia and China can make a significant contribution to improving global food security, as well as providing opportunities for commercial benefits to people who farm or fish, and agricultural and food businesses in both countries.

II. Cooperation based on common interests and respective advantages

Agriculture holds an important position in the national economy of both Australia and China. Both countries place a high priority on improving the productivity and output of their agriculture and fisheries sectors on an environmentally sustainable basis.

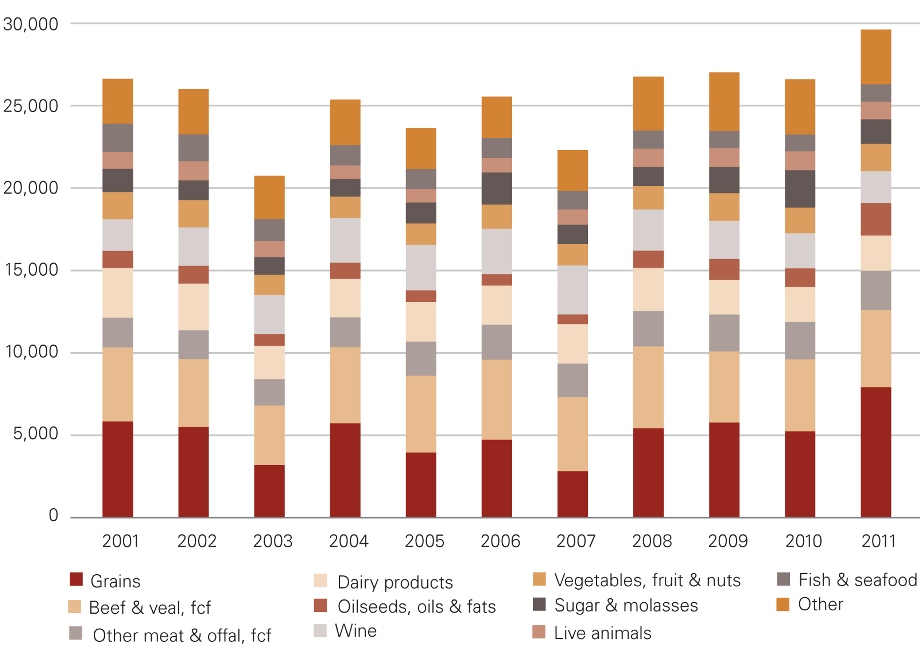

Australia and China are major food exporters and important agricultural trade partners–indeed, a significant trade in wheat began in 1960. In 2011, China's agrifood exports were US$60.1 billion and Australia's $29.6 billion. In 2011, China was the fifth-largest market for Australian agrifood exports, and Australia was the eighth-largest source country for China's imports of agricultural products. China was the third-largest source of agrifood imports into Australia, and Australia was the 11th-largest market for Chinese agrifood exports. Australia's agrifood exports to China were worth $1.9 billion in 2011; the largest items were barley and malt, wheat, milk powder, seafood, sheepmeat, edible offal and wine. China's agrifood exports to Australia were worth $0.8 billion in 2011; the largest items were processed fish and seafood, confectionery, fruit juice, bakery products and other processed foods (see Statistical annex).

The bilateral relationship between Australia and China in relation to agricultural investment and technology has been steadily increasing over the past four decades, in part because of the links to the expanding bilateral agrifood trade. By 2011 over 100 agricultural technology cooperation projects in China had been supported or aided by Australia. China's direct investment in Australia's agriculture and food processing sector in 2011 (flow) was US$19.5 million, with cumulative Chinese investment in the sector (stock) standing at US$47.1 million (MOFCOM 2012). The stock of Chinese direct investment in all sectors in Australia by 2011 was US$11 billion, according to Chinese records (MOFCOM 2012). Australian investment in China's agrifood sector is understood to be much smaller, as the stock of Australian direct investment in China in all sectors was $6.4 billion by 2011 (ABS 2012).

Australia and China have a common interest in steadily improving their capacity to supply agricultural products to satisfy the world's ever-increasing demand for agrifood products. An important part of this will be strengthening bilateral investment in the agrifood sector to increase sustainable production, improve the efficiency of distribution channels and markets, promote employment and the profitability of agricultural enterprises, and contribute to broader economic growth.

III. Opportunities to work together in investment and technological cooperation in agriculture

Against the above background, Australia and China conducted joint research on strengthening investment and technological cooperation in agriculture in order to address the challenges of global food security. This study is committed to providing a clear direction for obtaining mutual benefits from bilateral agricultural cooperation, and working to eliminate impediments to such cooperation. Amid widespread uncertainty about the rapidly changing global agrifood context, strengthening cooperation between Australia and China in the agriculture sector by developing and demonstrating a best-practice model can send a positive signal to the international community.

This joint Australia–China report focuses on:

- the current situation, opportunities and constraints for agriculture in Australia and China;

- the current situation, shared interests and complementarities, and the potential for future cooperation between Australia and China in investment and technological cooperation in agriculture;

- identifying the key fields for this potential future cooperation between Australia and China, and encouraging Australian and Chinese enterprises to explore the opportunities for agricultural investment and for the commercial exchange of new agricultural technologies; and

- working to remove impediments to investment and technological cooperation and improving relevant policies.

Chapter 2: Agriculture in Australia and China

I. Agriculture in China

(I) Overview

1. Agriculture has an important position in China's economy

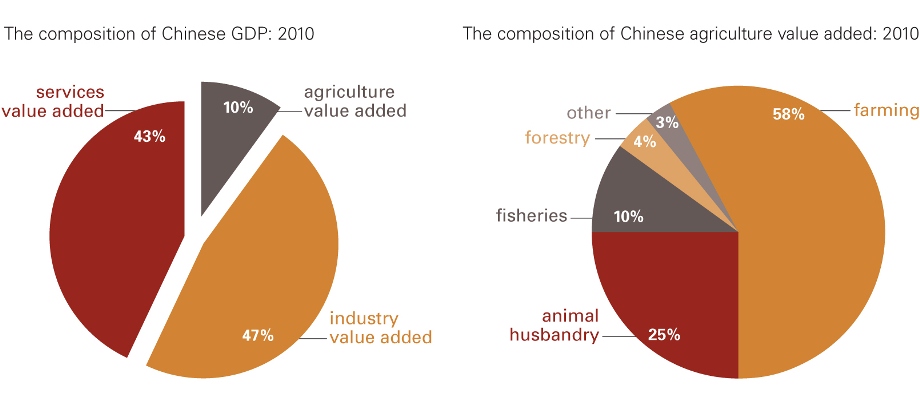

As a developing country with a population of 1.35 billion, China sees resolving its food security problem through its own efforts as a critical task. By the end of 2010, China's rural population was 670 million, just over 50 per cent of the total. In 2010 agricultural value-added reached 4.1 trillion yuan ($659 billion), accounting for 10.1 per cent of GDP, with crop farming comprising 58 per cent, animal husbandry 25 per cent, forestry 4 per cent, fisheries including aquaculture 10 per cent, and other 3 per cent (see Figure 2).

2. China maintains a high level of self-sufficiency for agricultural products

The Chinese Government successfully feeds 21 per cent of the world's population with just 9 per cent of the world's arable land (China's arable land area is 120 million hectares, equating to less than 0.1 hectares of arable land per capita). This makes an important contribution to global food security. Under the Chinese policy of using domestic resources to achieve self-sufficiency in the supply of grains and other agricultural products, a range of policy incentives have been introduced. Food production increased for eight consecutive years from 2003, with steady growth for major agricultural products. The supply of agricultural produce and products is adequate for China's needs, and the production of meat, dairy products and eggs is growing rapidly to largely meet domestic consumer demand.

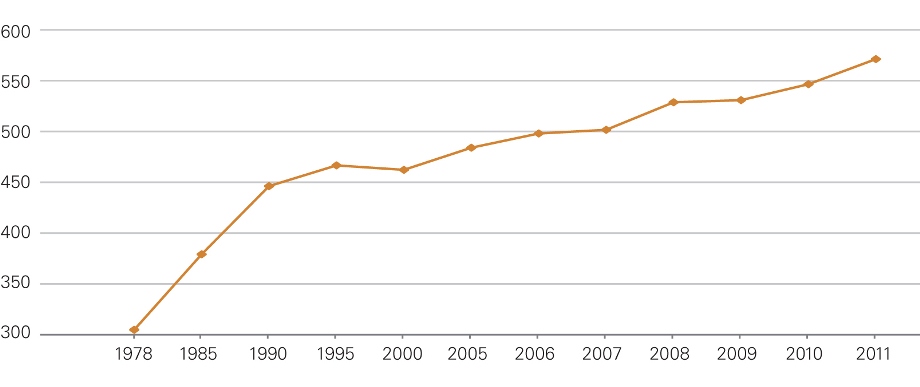

China's total grain output exceeded 500 million tonnes for five consecutive years, reaching a record 570 million tonnes in 2011. This was approximately 1.9 times production in 1978, the milestone year for China's economic and agricultural reform and opening-up (see Figure 3). This was equivalent to a per capita grain availability level of 408.7 kg. China maintains significant state grain reserves, and grain imports and exports are mainly for adjustments in bad or good harvest years and adjustments to the supply of different grain types.

(million tonnes)

3. Scientific and technological innovation in agriculture has become the major force to develop modern agriculture

Scientific and technological innovative capacity continues to grow. In the last five years, 2600 new varieties of staple crops have been developed. Up to 95 per cent of the area cultivated with these crops uses these improved varieties. As well, major animal diseases have been controlled by the research, manufacturing, promotion and application of livestock vaccines and medicines. Agricultural science and technology appropriate to China has been actively explored. As a result of improving its capacity for independent agricultural scientific and technological innovation, China has created a modern agriculture system, carried out new variety cultivation projects and scientific research projects in sectors for the public good (agriculture), which have effectively guided scientific and technological innovation in agriculture to concentrate on agricultural production. The contribution of agricultural scientific and technological progress to overall agricultural growth has reached 52 per cent.

(II) China's main agricultural development policies

To enhance China's agricultural development, the Chinese Government has implemented a suite of policies relating to agricultural production, the sale of resulting produce and foreign investment in agriculture.

1. Policies to improve domestic agricultural production capacity

- A strict arable land protection system to ensure the arable land area for agriculture is not less than 120 million hectares, and strengthening the arable land protection accountability system.

- Developing a range of policies and measures on increasing agricultural research and development (R&D) input, encouraging innovations in improved varieties and agricultural production technologies and strengthening the promotion of agricultural technology to continuously improve the contribution rate of scientific and technological progress in agriculture.

- Policies on increasing investment in agricultural and rural infrastructure to gradually improve agricultural production conditions through better infrastructure such as irrigation and water conservation, power supply and roads.

- Advancing the transferability of agricultural land and increased scale of production, developing specialised production organisations, and boosting large-scale production, standardisation, and modernisation of agricultural production.

- Encouraging sustainable agricultural resource utilisation and environmental protection, and developing a series of policies and measures on the rational utilisation and effective protection of agricultural resources, agricultural energy saving and emission reductions.

2. Policies on building a good market environment

- Reform of the agricultural product distribution system aimed at marketisation has been generally successful, and the prices for most agricultural products are generally determined by the market.

- China strictly complies with its World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments. In accordance with its Protocol of Accession to the WTO, China's tariff level has dropped significantly. China is committed to advancing fair and free trade in agricultural products, and is actively taking part in international agricultural cooperation.

3 Policies on foreign investment in agriculture

The Chinese Government attaches great importance to the use of foreign investment to promote the country's economic development. Agriculture is a key sector for utilising foreign investment and the use of foreign investment in agriculture maintains stable development. According to the 12th Five-Year Plan for International Agricultural Cooperation (MOA), during the "11th Five-Year Plan" period (2006–2010), total foreign investment in agriculture is about $4.6 billion, of which foreign direct investment is more than $4.1 billion.

- The Catalogue of Industrial Guidance for Foreign Investment is an important industrial policy for China to guide direct foreign investment. The revised Catalogue came into effect on January 30, 2012, which includes the relevant policies for farming, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery industries. (See Appendix 3 for the full list of encouraged, permitted, restricted and prohibited areas in agriculture.)

- China exercises an approval system for foreign investment (excluding for partnership/joint venture business1). The encouraged and permitted projects in the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries (production and infrastructure projects) with total investment exceeding US$300 million and the restricted projects with total investment of US$50 million and above must be ratified and approved by the central government of China. The projects with total investment lower than the approval threshold of the central government must be ratified by local government.

(III) Main agricultural planning and prioritised industries and fields

1. Main agricultural planning

The 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China (2011–2015) and the National Modern Agriculture Development Plan (2011–2015) define the overall arrangements and requirements of the Chinese Government on the development of agriculture and rural economy. In September 2011, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture issued The 12th Five-Year Plan for National Agricultural and Rural Economic Development. The Plan further clarified the overall goal of agriculture and rural economic development during the 12th Five-Year period: steadily and comprehensively improving productive capacity for grains and other major agricultural products, and making significant progress in modernising agriculture; substantially increasing farmers' income and quality of life; achieving remarkable results in new rural area construction, and coordinating the development of urban and rural areas. On this basis, China further developed specific plans for agriculture and related industries.

2. Prioritised industries and fields

The Chinese Government has prioritised the following areas of agricultural development:

- high yield and ultra-high-yield new varieties and supporting farming technology such as for cotton, rice and wheat;

- production and processing of vegetable, fruit, flowers and edible fungus;

- fresh water aquaculture and coastal aquaculture;

- animal vaccine production and immunisation;

- bio-pesticides and bio-fertilisers;

- molecular breeding technology of animals and plants; and

- deep sea fisheries and aquatic product processing.

(IV) Challenges facing agricultural development in China

1. Shortage of arable land and water resources

Currently the per capita arable land of China is less than 0.1 hectare, only about 40 per cent of the world's average. This number is declining due to continuing population growth, urbanisation and increased land usage by industry. The area of reserved arable land is insufficient; and the quality of much of the arable land is not very good, with moderate and lower yield land accounting for 67 per cent of the total. The Chinese level of per capita fresh water resource availability is about 2400 cubic metres, only one quarter of the world's average (for water availability, China is ranked 88th out of 153 countries in World Bank statistics2). The distribution of China's water resources is extremely uneven across the country, with severe water resource shortages in northern China.

2. Frequent natural disasters

China faces frequent drought and flood disasters. With the onset of climate change and frequent extreme weather events in recent years, the impact on agricultural production continues to deepen. Since 2004, grain losses caused by disasters exceeded 30 million tonnes per year and reached more than 55 million tonnes in 2009, accounting for 10 per cent of total grain production in that year.3

3. Weak agricultural infrastructure and support systems

Agricultural infrastructure is weak, particularly for irrigation and water conservation facilities, and about 60 per cent of cultivated land is affected by drought, salinity and other factors. The market trading system for agricultural products and the cold chain logistics system for fresh agricultural products are underdeveloped. Consequently, the capacity to respond to unexpected events and market fluctuations is limited.

4. Lower level of organisation in agricultural production and operation

China's agricultural production method is based on household units, and is characterised by its small scale and the less developed level of organisation in production and operation. Intermediary organisations such as farmer cooperatives and industrial associations face problems, like the small scale of operation, a limited capacity to drive change and less standardised internal management in some cooperatives.

5. Higher level of post-harvest losses

China's agricultural product storage, preservation, drying and other primary processing methods are simple and the facilities are underdeveloped. The corn post-harvest losses are as high as 8 per cent to 12 per cent. The potatoes post-harvest losses are as high as 15 per cent to 25 per cent. The fruits post-harvest losses are as high as 10 per cent to 15 per cent. The vegetables post-harvest losses are as high as 15 per cent to 20 per cent.4

II. Agriculture in Australia

(I) Overview

1. A major global agricultural producer

Australia is a reliable global agricultural producer, though farm and fisheries production accounts for around just 2.4 per cent of Australia's GDP, with a gross production value of $50.3 billion in Australia's financial year 2010–11 (ABARES 2012).

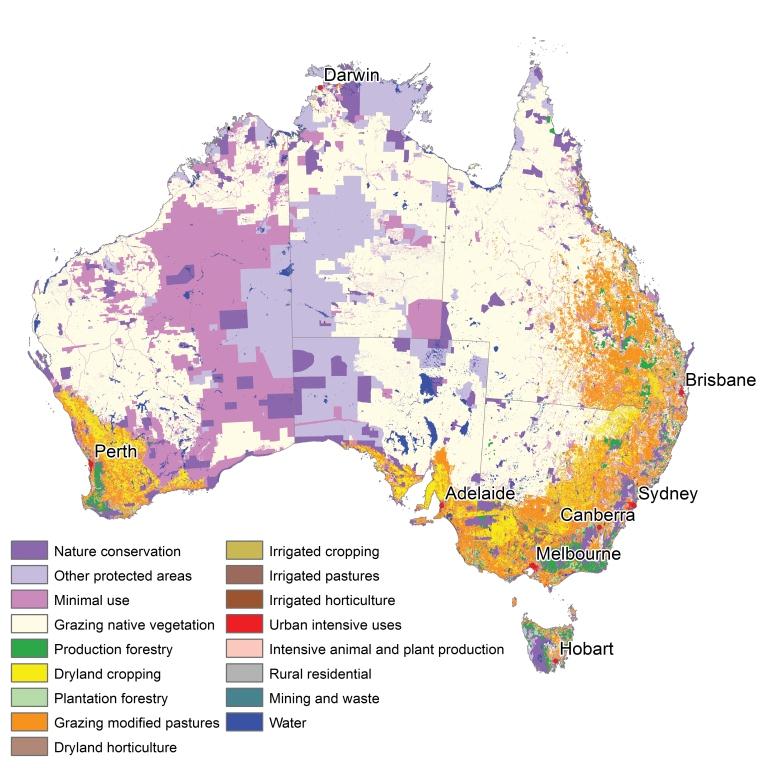

Agricultural production and yields vary widely across Australia, reflecting the different geographical and climatic conditions (see Map 1).

Australia is a major producer of broadacre crops (see the Statistical Annex). Between 2006 and 2010, Australia's sowing area for winter crops ranged between 20 and 23 million hectares, and for summer crops between 9 and 13 million hectares. Wheat production is highly dependent on rainfall between April and November. Under favourable seasonal conditions, production is generally between 24 and 25 million tonnes. An average of around 13 million hectares is planted annually. The main coarse grain grown in Australia is barley, used principally for livestock feed and malting. Production of barley was around 8.1 million tonnes in 2010–11. An average of around 4.5 million hectares is planted annually. Grain sorghum, which is used for livestock feed, is the second-highest produced coarse grain in Australia. Production of sorghum was around 2.1 million tonnes in 2010–11 (DAFF 2012b).

Around 95 per cent of Australia's sugar comes from Queensland and the remainder from northern New South Wales. Harvested areas of sugar cane in Australia have declined since 2002–03 because of a range of factors, including relatively low world prices, drought, cyclones, urban encroachment and higher returns from alternative land uses, particularly forestry. In 2010–11, 334,000 hectares was planted, producing 3.6 million tonnes of sugar (DAFF 2012b).

Australia is also a major livestock producer, notwithstanding the low rate of stocking in much of the country. Beef production is widespread across Australia, with an average of 27.5 million head of cattle and a production of 2.1 million tonnes of beef. Australia's dairy herd of 1.6 million cows produces 93.1 billion litres of milk, with a yield of over 5,650 litres per cow. The Australian pig herd was around 2.3 million head in 2010–11 and pork production was 342,000 tonnes. Australia's 73 million sheep are reared for both wool and meat, producing over 620,000 tonnes of meat (DAFF 2012b).

Key factors underlying Australian agrifood production are:

An open and competitive economy

Tariffs are low and agricultural producers receive government funding support for just 3 per cent of their income, the second-lowest in the OECD. These factors, along with competitive markets, have broadened the sources of food for Australians and expanded consumer choice. Australia's imports of food, beverages and fishery products have grown. In 2011 imports totalled $11.6 billion compared to exports of $29.6 billion.

An emphasis on food safety and biosecurity

Australia is free of many pests and diseases found in other countries, including major livestock diseases such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and foot and mouth disease (FMD). Maintaining this largely disease-free status is a priority. So too is maintaining high levels of food safety, both for exports and domestic consumption. According to the OECD, Australia ranked equal first with Denmark and the UK for food safety performance in 2010.

A strong R&D base

Australia's agrifood productivity growth is driven, in part, by the strong agricultural R&D base, including networks linking universities, government and specialist research centres. Sectoral R&D is funded equally by both government and producers.

Efficient supply management

Australia's agricultural supply-chain management functions well, though constant effort is needed to improve efficiency and cost-competitiveness. The expertise and infrastructure to transport agrifood products reliably, safely and in a timely manner helps to make Australia one of the world's leading agricultural exporters. It is also important in ensuring high levels of quality and safety for domestic and international consumers.

2. . . . with strengths in many fields . . .

Australia has developed many strengths, including:

- animal, plant and environment biosecurity;

- livestock genetics (cattle, sheep, goats) and live animal exports (cattle, sheep, goats);

- fodder and livestock management;

- broadacre cropping (wheat, canola, barley, sorghum);

- dry land farming and some areas of horticulture;

- sustainable management in both agriculture and fisheries (including aquaculture);

- high quality fish and seafood production, both wild and farmed;

- probiotics, nutraceuticals and other dairy product diversification;

- food and livestock traceability;

- agricultural inputs and services; and

- farm management and extension training.

3. . . . and a net contributor to global agrifood supplies

Australia currently produces sufficient food to feed up to 60 million people but has a population of less than 23 million. The export of surplus agricultural products increases global food supplies. This, when combined with accessible and efficient global agricultural and food markets and supply channels, helps reduce market and price volatility and thereby helps improve global food security.

Notwithstanding this considerable surplus, Australia's share of total global agrifood production is quite small overall (around 3 per cent), much less than China's. For some important agrifood products, however, particularly beef, sheepmeat, wheat, barley, sugar, dairy, canola and pulses, Australia is a significant global exporter. In 2011 Australia ranked 17th among food exporting countries, with 2 per cent of total global exports. (WTO 2012; see also Figures 7 and 8 below, and Appendix 1).

($ million)

Source: DFAT STARS database, based on ABS data

Australia is expected to continue to produce a surplus even as domestic demand grows (Linehan et al. 2012). This growth in Australian demand will flow primarily from an increase in population: the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates Australia's population will be more than 35 million by 2056, on current trends (ABS 2010). Current trends in Australia's consumption profile are expected to continue: consumers are likely to continue to favour high-protein, highly processed, convenience-oriented food, with an emphasis on quality, safety and traceability. As demand grows, Australia's imports of food–mainly out-of-season produce and highly processed foods and beverages–are also expected to increase (DAFF 2011). However, the increase in domestic food demand in Australia will be insignificant compared to the major expansion in food demand in other parts of the world, especially Asia.

(II) Foreign investment in Australia's agricultural sector

1. Foreign investment is beneficial

Australia welcomes foreign investment. Foreign capital has always supplemented domestic savings to drive employment and prosperity, including in agriculture. It can help farmers, agricultural enterprises and food processors and manufacturers diversify, become more competitive and boost incomes. It helps sustain Australia's agricultural productivity and economic prosperity more broadly.

Foreign investment has often been associated with the introduction of new technologies or improvements in existing technologies, and improved access to markets. Direct investment in cattle raising, the use of feed-lots and processing in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s onwards contributed to the significant expansion of Australia's beef exports to Japan and later the United States. Japanese and US companies' investments in the development and growth of Australia's cattle industry lifted its export competitiveness not only for the Japanese and US markets but also for other high-value markets. Similarly, significant international investment in the Australian wine industry helped improve wine production and distribution systems, and helped drive growth in wine exports to European and other markets.

The RIRDC/ABARES report Foreign Investment and Australian Agriculture (Moir 2011) concluded that foreign investment in the agricultural sector enhances Australia's food security by increasing efficiency and productive capacity. It adds to incomes, infrastructure and employment, often in regional areas.

2. Australia is an attractive destination for foreign investment

Australia is a globally competitive location in which to do business: home to rich and abundant natural resources, a highly skilled workforce, a culture of innovation, a robust legal system and political stability. The certainty provided by Australia's legal and political systems makes sovereign risk low. The Australian food industry enjoys a reputation as one of the world's best for food safety and food quality. This is attracting the world's leading food production companies to invest in the Australian market.

One factor that affects foreign investment in Australia is the barriers to imports that exist in foreign markets. These affect exports not only from Australian-owned companies, but also foreign companies that have invested in Australia. As Chinese investment in Australian agriculture increases, Chinese companies will similarly face barriers in export markets.

3. Australia's policy on foreign investment

The Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 and Australia's Foreign Investment Policy provide the framework for the Government to review foreign investment proposals. The Government, through the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), reviews foreign investment proposals against the national interest on a case-by-case basis. Elements of the national interest typically taken into account include: national security; competition; other Australian Government policies such as taxation; the impact on the economy and community; and the character of the investor. Generally, private sector investment above $244 million (as at 1 Jan 2012; indexed annually) is subject to review.

All proposals by foreign governments and their related entities for making a direct investment, starting a business or acquiring land are subject to review. In the case of proposals by foreign governments and their related entities, the Government also considers if the investment is commercial in nature or if the investor may be pursuing broader political or strategic objectives.

The Treasurer can block proposals that are contrary to the national interest or apply conditions to a proposal to address national interest concerns. Only two business cases have been blocked in the past ten years, one in the resources sector and one in the financial services sector. Between 2007–08 and 2010–11, no Chinese investment proposals were rejected, and around 270 were approved.

4. Foreign investment policy in the agricultural sector

The Australian Government recognises the benefits that foreign investment in the agricultural sector can bring, consistent with protecting Australia's national interest. The Government's 18 January 2012 Policy Statement on Foreign Investment in Agriculture provides detailed guidance on specific factors typically considered in relation to proposed acquisitions in the agricultural sector. These include the impact on:

- the quality and availability of Australia's agricultural resources (including water);

- land access and use;

- agricultural production and productivity;

- Australia's capacity to remain a reliable supplier of agricultural products to both the Australian community and trading partners;

- biodiversity; and

- employment and prosperity in Australia's local and regional communities.

There are concerns in some parts of the Australian community about the sale of rural land and agricultural businesses to foreign investors. Consequently, the Government has taken steps aimed at ensuring that its policy is well understood and to strengthen the transparency of foreign ownership of rural land and agricultural food production. These steps include funding the Australian Bureau of Statistics' ongoing Agricultural Land and Water Ownership Survey and establishing a register for foreign-owned agricultural land. Transparency in foreign investment in the agriculture sector is important in providing reassurance to Australian citizens and foreign investors alike.

(III) A policy framework

The Australian Government is finalising Australia's first-ever National Food Plan. This will be a framework that guides on-going activities within the Australian food system to ensure that Australia has a sustainable, globally competitive, resilient food supply which supports access to nutritious and affordable food. The Plan also seeks to ensure that Australia continues to be a reliable surplus food supplier to international markets as part of its contribution to global food security.

(IV) Challenges to Australia's food supply

1. Restricted land and water resources

Although a large country, Australia's agricultural productive base is limited and the often poor soil quality affects production. Compared with soils in the northern hemisphere, Australian soils have less organic matter, low levels of phosphorous and other nutrients, and poorer structure that results in reduced nutrient storage and water-holding capacity.

Excluding Antarctica, Australia is the driest continent, and agricultural productive capacity is affected by rainfall distribution. Long-term average annual rainfall varies from less than 300mm per year in central Australia to more than 3000mm in northern Queensland (see Map 2). Runoff into rivers is low–on average, only a tenth of this rainfall is captured in rivers or subterranean aquifers (National Water Commission 2012)–compared with a world average of 65 per cent. Substantial use of irrigation in parts of the country has placed pressure on ecosystems that also rely on the nation's water.

Source: Bureau of Meteorology

2. Adverse effects of climate change on agricultural production

Climate change has the potential to change agricultural productivity at a regional level. For example, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the Bureau of Meteorology estimate that southern Australia will experience a decline in average rainfall in coming decades. Significant weather events such as drought, fires, floods and cyclones may increase in frequency and/or strength, with effects on annual yields. This is a major policy focus for the Australian Government. Research and development programs which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural activity while increasing productivity and responding to the impacts of climate change are a priority.

3. Slower productivity growth

Similar to the problems experienced in other countries, a fundamental challenge for Australia is the need to respond to the recent slowing in the rate of growth of agricultural productivity.

Research by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES 2012) found that Australian farms achieved average total factor productivity growth of 1.2 per cent per annum between 1977–78 and 2009–10 (see Figure 6). This rate of productivity growth is higher than most other Australian industries. However, while the long-term trend is positive, the average growth rate has declined in the last 10 years. This decline can be partly attributed to reductions in R&D investment in the sector. Future increases in production will require positive productivity growth rates, which, in turn, will require ongoing investment in research and development (Linehan et al. 2012).

(index, 1977-78 = 100)

4. Further investment is required in logistics and other agricultural infrastructure

Transport costs are a significant proportion of total farming costs; up to 21 per cent of the value of grains produced in Australia is spent on transport (Tulloh and Pearce 2011). Many Australian farms are located considerable distances from ports or other transport hubs and from processing plants. Weather also imposes logistical constraints: monsoonal rains mean that some roads in northern Australia are inaccessible for months each year.

5. Younger, better-skilled workers are needed

Australia faces challenges with its agricultural workforce. The average age of workers in the sector is increasing. The current mining and resources boom has exacerbated agricultural workforce pressures. It is also estimated that the number of agricultural graduates produced every year in Australia may only be one-fifth of total demand (Office of the Chief Scientist 2012). This trend is partly countered by the increase in the average size of agricultural holdings, increasing mechanisation and other technological advances. For example, a farm of approximately 1000 hectares in the Ord region of Western Australia would only need between three and six permanent staff, depending on the crops produced and farming methods. The Australian Government is examining ways to address these challenges and to encourage younger Australians into agriculture.

6. Post-harvest losses

Estimates of post-harvest losses range from 10 to 40 per cent (Keating and Carberry, cited in Moir and Morris 2011), so even a small reduction in wastage would have a positive effect on productivity. Additional government and private investment in infrastructure will be required, especially if there are shifts in where food is grown or processed as a result of changes in climate or the introduction of new technology.

Chapter 3: Investment and technological cooperation in agriculture

I. Investment in agriculture in Australia and China: the current situation and future prospects

(I) Chinese agricultural investment in Australia

1. Chinese investment in Australian agriculture is in its infancy...

Chinese investment in Australian agriculture is in its infancy, with investment projects small in number and size. According to China's Ministry of Commerce, investment in Australian agriculture accounts for a small proportion of Chinese investment in Australia (see Figure 7). Chinese investment accounts for a small proportion of total foreign investment in Australian agriculture. According to Australian statistics, which do not provide a breakdown by sector for each country, China ranks 10th in terms of the stock of total foreign direct investment in Australia, and the stock of its investment constitutes 2.6 per cent of the total stock of foreign direct investment in Australia.

(US$ million)

State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People's Republic of China

2. ...but is growing...

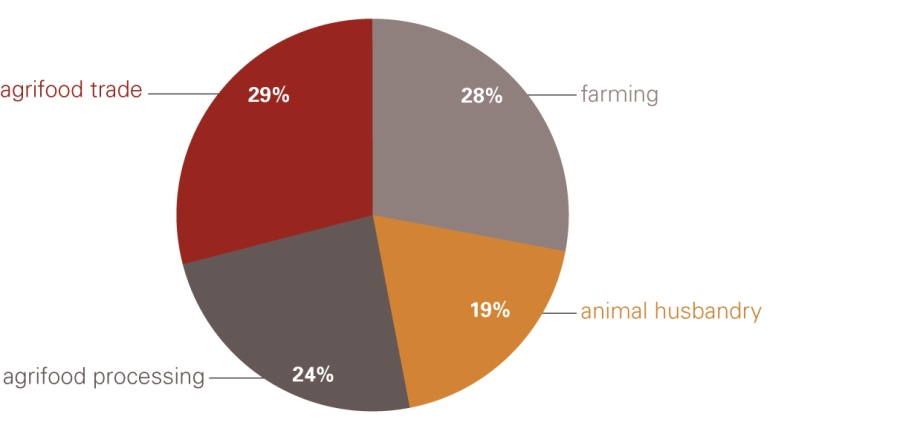

In recent years, Chinese enterprises have had increasing interest in investing in overseas agriculture, and China's outward investment flows to the agricultural sector have increased from US$170 million in 2008 to US$650 million in 2011 (see Figure 8).

(US$ million)

Source: 2008–2010 statistical bulletins of China's Outward Foreign Direct Investment, China's Ministry of Commerce, National Bureau of Statistics,

and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People's Republic of China

The scale of Chinese investment in Australian agriculture and food processing is increasing. Chinese direct investment in agrifood in Australia in 2010 was US$3.23 million, with cumulative FDI (stock) of US$22.5 million (MOFCOM 2011). This increased in 2011 to US$19.5 million, with a stock of US$47.1 million (MOFCOM 2012). According to an annual survey of investment intentions, existing or planned Chinese investment in Australia amounted to about US$700 million by the end of 2011, a relatively large increase compared with 2010.

3. ...and becoming more diverse

The scope of investment is expanding to cover planting, breeding, farming, and food processors and traders (see Figure 9). As well, the range of investors is more diverse. In addition to state-owned enterprises, publicly listed and private companies have gradually become the main Chinese investors in Australia. The mode of investment is also more diverse. In addition to greenfield investment, the level of Chinese involvement in agriculture-related commercial transactions including mergers and acquisitions has increased rapidly. Finally, the location of investments is gradually expanding. Promising new areas for investment include the relatively underdeveloped areas of northern and northwest Australia.

Source: Market research data provided to MOFCOM

(II) Australia's current agricultural investment in China

Australia's total stock of FDI across all sectors in China was $6.4 billion in 2011. Although neither Australian nor Chinese data record Australian agrifood investment in China, anecdotal evidence suggests it is growing, albeit from a very small base. Increasing food demand in China has given rise to significant commercial opportunities. Agrifood investment is believed to constitute only a small fraction of Australia's total FDI in China. Currently, Australian agrifood investment in China is developing around two main industry subsectors:

Sales of agrifood products

A number of Australian companies have invested in China in order to expand their sales of agrifood products in the Chinese market, including Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co. Ltd and Goodman Fielder.

Agribusiness services

Other companies such as Nufarm, Elders and Toll Group are providing logistical and other agribusiness services, all aimed at the Chinese market. As well, a number of Australian financial sector firms, including the Australian and New Zealand Banking Corporation (ANZ) and the National Australia Bank are providing banking services to Chinese agribusiness firms. As China's rural areas are currently underserviced in terms of financial services, ANZ established the Chongqing Liangping ANZ Rural Bank in September 2009. The rural bank, which focuses on agricultural-related business in the local area, is now profitable with a solid customer base, providing the company with experience in China's rural business sector and allowing it to tap into the many business opportunities arising from the region's rapid growth.

Australian investment in China is not limited to Australian-owned companies. Some Australian subsidiaries of foreign firms have already invested in different parts of China's agricultural and food sector.

There are many reasons for the relatively limited levels of investment by Australian firms in China's agrifood sector. In general, few Australian agrifood businesses invest offshore, reflecting the structure of the sector with its predominance of smaller, family-owned farms and the increasing prominence of foreign-owned food processors.

(III) Prospects for strengthening agricultural investment

The sustainability of agriculture is significant for Australia, China and the world. Both Australia and China have issues that need to be addressed in order to improve sustainability.

Cooperation between Australia and China will benefit both Australian and Chinese producers. Continued investment will help them remain competitive and sustainable food producers. Success in resolving these problems, especially in sectors such as dryland farming, can be shared with other countries, enabling Australia and China to contribute to global food security.

There are a number of areas where increased investment could deliver potential benefits by expanding production or improving productivity.

1. Developing water and soil resources in northern Australia

Australia's main traditional agricultural zone (the south-east of the continent) is relatively well-developed. Agricultural production here can be increased by improving efficiency. Northern Australia, with its tropical climate and significant land and water resources, has significant potential for productive large-scale development. It may become a new growth area in Australian agriculture, although considerable further research and commercial-scale demonstration is required.

2. Commercialising proprietary technology and new varieties

Successfully commercialising potential proprietary technologies and new varieties of crops and breeds of animals of both countries, with appropriate intellectual property protection, would deliver considerable economic benefits. Potential projects include the artificial propagation of aquaculture products like Australian lobsters, cultivation of quality embryos, and soil reclamation. China's equipment andagriculture technology also have good prospects for application in Australia.

3. Processing agrifood products

Many of Australia's agricultural products are exported with no or limited processing. With improved infrastructure in logistics and processing, there will be more opportunities for further processing of agricultural products. China's agricultural production mainly comes from small-scale operations, which have a lower level of business organisation, and are less able to process food. Considering the domestic requirements in both countries for processing, convenience, food safety and traceability, as well as international requirements, it is also necessary to increase investment and cooperation in agricultural processing and further promote the production and processing ability of both countries.

4. Modern supply-chain logistics

As the movement of agricultural products increases, both countries would benefit from increased investment in cold chain, warehouse and logistics infrastructure, including ports, related infrastructure, and transport and distribution networks. Increased bilateral trade would increase logistical efficiency and lower logistics costs for the movement of food between Australia and China.

II. Current cooperation between Australia and China in agricultural technology and future opportunities

(I) China's agricultural technology level

1. Recent achievements and current levels of agricultural technology

The continuing development of agricultural technology is fundamental to ensuring national food security. In terms of agricultural scientific and technological research, the Chinese Government has carried out a series of programs that adapt such research to China's mode of intensive cultivation. They aim to increase output, centering on the basic goal of meeting the food demand of a huge population with limited agricultural resources. Such programs include, for example, research projects on breeding various crops and associated agricultural skills and machinery; livestock and poultry breeding programs and associated animal nutrition; and environmental control of plant growth, disease control and research. This has produced some strong results, for example, lifting the yield per hectare of several of China's staple crops, namely wheat (4.7 tonnes per hectare), corn (5.5 tonnes per hectare), rice (6.6 tonnes per hectare) and seed cotton (2.1 tonnes per hectare), accounting for 158 per cent, 105 per cent, 150 per cent and 174 per cent of the world average.

China has made breakthroughs in many research fields, which have contributed to world food security. For example:

- China created the world's first ideal tool for wheat colony improvement: dwarf male-sterile wheat which can continuously cultivate new varieties of wheat in a large batch and improve the breeding efficiency manyfold.

- Hybrid rice research, led by Professor Yuan Longping, who was awarded the World Food Prize in 2004, changed the traditional understanding that rice is self-pollinating with no hybrid advantage, and created a new breeding method. In 2011, China's super hybrid rice target yield of 900 kg per mu was achieved successfully, and Chinese super high yield hybrid rice research continues to maintain a leading position in the world.

On the application of agricultural technologies, China closely follows world agricultural technological developments, and has made outstanding achievements in many fields:

- In crop breeding, China has adopted hybrid breeding, mutation breeding, polyploidy breeding, molecular marker breeding, transgenic breeding and other technologies, and China takes a leading role in the hybrid advantage utilisation and transgenic breeding of some crops in the field.

- In livestock and poultry breeding, the technologies of molecular marker-assisted breeding, transgenic animal breeding, artificial insemination, embryo transplantation, and gender control technology have been applied in production and practice, and China has reached an internationally advanced level especially in animal bioreactor and animal somatic cell cloning technology.

- China has taken a leading role in plant disease and insect pest prevention and control technologies, and made rapid progress especially in botanical pesticides, microbial pesticides, and the use of animal natural enemies for biological control.

- China has made significant achievements in animal disease prevention and control, especially in developing the attenuated disease (bacteria) vaccine, and has taken a leading role in bird flu vaccine development.

2. New requirements in agricultural technology development

Though China has rapidly developed agricultural technologies and made outstanding achievements in many fields, there are still some gaps, mainly reflected in the following aspects:

- China has carried out extensive research in staple crops such as rice, corn and wheat, but started late in the development of vegetable, fruit and flowers. Similarly, China has done extensive research in pig breeding but started late in dairy cow breeding and other fields. Generally speaking, research and development among different agricultural sectors has not been even.

- Though China has abundant animal and plant genetic resources, it has not done sufficient basic research on the genetic functions, and its advantage in genetic resources has not been transferred to production and practice.

- China has focused on breeding to increase yields, and placed insufficient emphasis on developing crop quality and stress-resistant varieties. The excessive dependence on chemical fertiliser and pesticide has led to less technical research in environmental improvement measures; and there has been insufficient research into measures and instruments to speed up quality inspection of food and disease diagnosis.

- China has focused its research on producing agricultural technologies, but neglected research on processing equipment, veterinary drugs, pesticides, and production-line equipment for agricultural processing, and is not yet able to satisfy production needs.

(II) Australia's agricultural technology level

Australian governments have long invested in agricultural research and innovation, and Australian researchers have a record of world-class scientific results. A recent report by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE) found that Australia's agricultural and biological sciences are its most specialised area of research relative to the rest of the world. Australian research in this field also has a citation rate above the world average (DIISRTE 2012).

Australia's agricultural expertise mainly includes the following areas:

Sustainable agriculture

This includes techniques and technology that improve soil condition, water quality and biodiversity outcomes and reduce the impacts of invasive species. The sustainable practices promoted include controlled traffic farming (confining the impact of machinery wheels to permanent intra-crop lanes), systems to increase perennial vegetation in pastures and conserving native vegetation. Precision agriculture technologies can be used in both dryland and irrigated agriculture.

Low-carbon farming

Australia's Carbon Farming Initiative (CFI) is the first federally legislated agriculture and forestry offset market in the world. It covers a broad range of eligible offset activities for sequestering carbon in vegetation and soils and reducing agricultural emissions of methane and nitrous oxide.

Plant genetic resources