Key questions

Was the scale of Australia's response appropriate?

What were the triggers for the crisis and were they appropriate?

What were the contextual and other constraints, and were these dealt with effectively?

What were the strategic priorities and were they appropriate?

Was the response to the crisis timely?

Did the breakdown of Australian assistance to countries and sectors align with strategic priorities?

3.1 Scale of funding

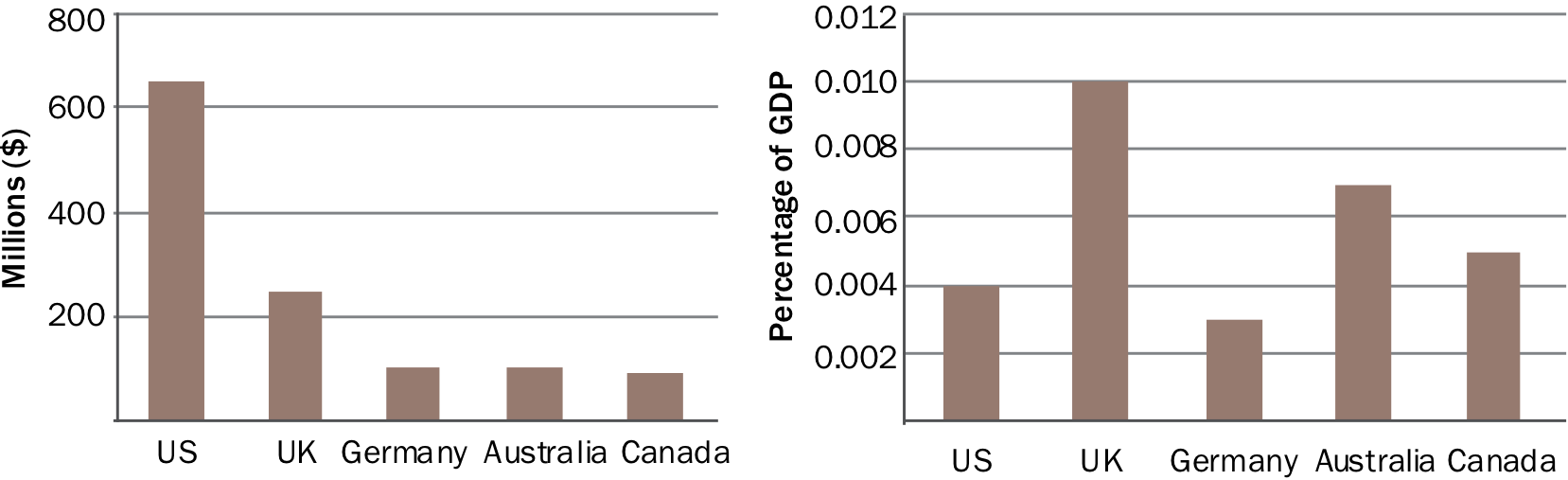

Australia contributed a total of $112 million to the Horn of Africa (HoA) crisis in 2011, which put Australia in the top five country donors, both in absolute terms and relative to gross domestic product (Figure 2). Australia does not have strong historic links to the HoA, nor is East Africa a region of primary geopolitical and commercial interests. It is to the credit of Australia that it responded to the HoA crisisÂand Somalia in particularÂat a level in keeping with the magnitude of the crisis, one of the worst this century has seen.

Figure 2 Financial allocations to the HoA crisis made by country donors in 2011 in actual amounts (left) and as a percentage of gross domestic product (right)

Conclusion

- Australia's response was in keeping with the scale of needs in the crisis.

3.2 Triggers and constraints

The failure of the international humanitarian community to take early action in response to the crisis in the HoA is well documented in academic and policy literature.15 When the United Nations (UN) declared famine in Somalia in July 2011, the crisis was already severe.16 Many people died before funding was significantly increased in response to the declaration, with implementation of large-scale relief programs coming even later.

Australia, like the vast majority of donors, responded to scale when famine was declared in Somalia in July. Nevertheless, documentation and interviews showed that the Nairobi Post and the Africa Section in Canberra identified early in 2011 that the situation was deteriorating and tried, with some success, to secure funding. In March 2011, $3 million was granted to the United Nations Common Humanitarian Fund for Somalia (CHF), run by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Other grants made in the run-up to the declaration of famine are listed in Table 4. A question for this evaluation is whether Australia should have made major funding commitments before the declaration of famine.

The lateness of the international response is seen by many as an unacceptable failure of major donors and the UN, given they had clear and compelling evidence of how bad things were at the beginning of 2011.17 As a result of Somalia's long civil war and its history of food insecurity, the international humanitarian system has developed a sophisticated monitoring and early warning system for famine. The two key components of this system are the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET), backed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU) hosted by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for Somalia. These monitor meteorological data, crop production, nutritional status, movement of people due to conflict or hunger, and other pertinent indicators.

Table 4 Grants made in advance of the famine declaration

|

Agency |

Amount |

Purpose |

Date provided |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kenya |

|||

|

United Nations (UN) World Food Programme |

$4 000 000 |

To improve food security in the semi-arid areas of Kenya, and provide assistance to Somali and Sudanese refugees |

May 2011 |

|

UN World Food Programme |

$1 000 000 |

To improve food security in the semi-arid areas of Kenya, and provide assistance to Somali and Sudanese refugees |

July 2011 |

|

Somalia |

|||

|

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

$3 000 000 |

To support high-priority humanitarian activities in Somalia |

March 2011 |

|

Save the Children |

$1 163 000 |

To develop and implement disaster risk-reduction activities in the drought-stricken region of Hiran in south-central Somalia, and to extend disaster risk reduction work with secondary school children and communities in Kenya |

June 2011 |

By early 2011, reports being produced by both FEWS NET and FSNAU warned of an impending crisis in Somalia.d Although these reports are technical and deal in probabilities rather than certainties, they made it clear that food shortages were severe. These warnings were recognised but not acted on for a number of reasons. Somalia had been 'bad' before and never tipped over into famine. Rains were seldom consistent. Warnings were often dire yet somehow ordinary Somali people have survived from year to year. The poor harvest towards the end of 2010 was expected to have been partly mitigated by the good one earlier in the year and Somalia's extensive remittances. Additionally, agencies may have developed a habit of betting on the next rains.18 Donors were also wary of significant investment, since without a declaration of famine, it is hard to justify the prioritisation of scarce resources to one crisis over another.

However, relying on a declaration of famine or pressure from the media before acting leads to unnecessary death and suffering. For famine to be declared, many people have already died and many others would be about to die. It is also inefficient in terms of resources. Once famine is declared, it takes time to mobilise resources and then implement humanitarian programs.19 It costs a lot more to feed people on the edge of starvation than it does to pre-empt it.20 There needs to be a solution to this challenge. It also needs to be a collective solution to ensure that donors like Australia invest in it.

In hindsight it is clear that the critical issue in the worsening famine was the war and the sanctions strategies. International counterterrorism policies and Al-Shabaab restrictions and expulsions dramatically reduced humanitarian resources and reach. These sanctions, along with the remoteness of the operation in Somalia and its very high dependency on interpersonal trust, shaped a culture of uncertainty that seriously compromised the possibility of taking action in 2010 and early 2011.

These limitations do not excuse the lack of early action, as the interagency evaluation makes clear.21 However, it did mean that donors like Australia that did not have a long history in the region looked to donors that had been in the region longer and had greater resources to provide some of this analysis. The partial failure of the United Kingdom22 and the United States of America to act early, for instance, meant it was less likely that Australia, and donors like Australia, would act early.23

The Australian aid program had an additional set of constraints as they were in the early stages of establishing a regional East Africa office. This meant that although they had an experienced and capable head of office, only about a quarter of the 20 or so staff they intended to recruit was in place. The Australian High Commission was also being expanded to accommodate the growth plan, meaning that the Australian aid program was in temporary accommodation, making official communication and access to corporate documentation difficult.

Conclusions

- Australia, like other donors, did not respond at scale in time for many of those who died during the famine.

- The Australian aid program was constrained in its ability to respond due to limited information, being new to the region, and being in scale-up mode.

- The Australian aid program recognised there was an impending crisis in Somalia early and secured some funding before famine was declared.

- In future responses to slow-onset crises, signals other than the declaration of famine need to be identified and prioritised to facilitate early action.

3.3 Strategic approach

The Australian aid program's strategy for this crisis was never formally written down. The evolving nature of the funding envelope and the fast pace of events in the early days of the response made developing a strategy challenging. A formal written strategy would have helped the team better articulate their need for support. A clear strategy would also have helped to shift thinking from a reactive to a proactive mind-setÂone that was trying to effect and monitor specific outcomes. Nevertheless, a number of sound key strategic decisions were made:

- Geographic focus: A key decision was to focus funding on Somalia despite the risks and inherent difficulties. This was appropriate because the epicentre of the crisis, and therefore the needs for humanitarian assistance, were greatest there. In recognition of the massive displacement of people, funding was also provided to support Somali refugees in Kenya and in Ethiopia. The geographic areas where non-government organisations (NGOs) provided assistance were primarily determined by their existing operations and were not strongly influenced by the Australian aid program.

- Sectoral focus: In funding UN agencies, a limited number of sectorsÂfood assistance and support for displaced peopleÂwere prioritised. The intention behind these decisions was clear and appropriate: to provide the assistance needed most urgently to stop people dying. The Australian aid program had little influence on the sectors where NGOs provided assistance.

- Partner focus: The overall strategy was to limit funding to a small number of agencies, including some that had already navigated access constraints. A key decision was to focus funding on UN agencies with most funding going to the World Food Programme (WFP) (see Section 4.6). In hindsight, it may have been better to allocate proportionally more funding to UN agencies and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which were already fully operational and able to access critical areas in Somalia. More funding should have been directed to partners that were using, or were willing to increase their use of, cash transfers.

- Flexible funding: The Australian aid program worked with partners to identify broad objectives, but gave them the flexibility to decide what they funded within sectors and modalities. Ensuring flexibility for partners in a complex changing environment with lots of donor demands was an important well-founded decision. This was also done to recognise that the aid program had limited capacity to determine the most appropriate earmarking and that this was best done by implementing partners.

- Management: Nairobi Post worked to make the overall system deliver results, which was a relevant and appropriate strategy. It saw them looking at the big picture rather than trying to micromanage every grant. Realistically, it was also the only strategy available given the human resource levels.

The strategy was carried out in three main ways in Somalia. The Australian aid program closely supported the Humanitarian Coordinator and OCHA, promoted and led donor coordination, and engaged robustly with WFP to ensure it delivered where they were operational.

Management of assistance in Ethiopia and Kenya was more hands off. The light touch in Ethiopia and Kenya raises the question as to whether Australia should have responded at all in these countries, especially Ethiopia. Ethiopia certainly deserved assistanceÂthe need was real and the response well executed (in the main)Âbut the Australian aid program was already stretched managing its response in Somalia. In the future, it may be sensible to focus more geographically, with a potentially clearer impact.

Conclusions

- There was no formal written strategy to guide the response or articulate priorities.

- The strategic decision to focus the bulk of funding on food assistance and Somalia was appropriate given the famine was most acute in Somalia.

- Supporting the refugee response, providing flexible funding and investing effort in making the response work overall were appropriate strategic decisions.

- In hindsight, proportionally more funding should have been directed to agencies with access to worst-affected areas and agencies that used cash transfers as a form of assistance.

3.4 Funding by partner

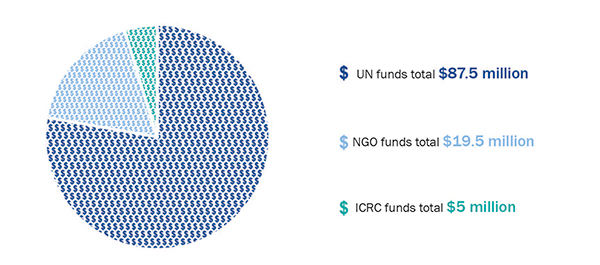

In 2011, the bulk of Australian assistance, about 80 per cent, went to UN agencies with a heavy focus on WFP (Figure 3, Table 5). The focus on WFP indicates that the Australian Government prioritised strong returns in the reduction of malnutrition and the eradication of famine. Further support for food security came from allocations to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and to FAO. The prioritisation of refugee support was evidenced by the allocations to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). The UN Department for Safety and Security was also funded.

Figure 3 Australian financial assistance by type of agency

ICRC = International Committee of the Red Cross; NGO = non-government organisation; UN = United Nations

Note: NGO funding includes all funding allocated through the Dollar for Dollar Initiative as well as through other means. Some of the organisations funded through the Dollar for Dollar Initiative directed funding to UN agencies. Some of the funding provided to UN agencies was used to support other organisations.

Funding was also given to the United Nations Common Humanitarian Fund (CHF)Âa pool of emergency funding administered by OCHA. In Somalia, the CHF funded international and local (Somali) NGOs, which provided the majority of the implementing capacity. This was one of the few sources of funding for Somali NGOs beyond partnering with UN agencies or international NGOs.

Internally displaced peopled in the Sigale Camp, Mogadishu, Somalia. Photo: Graham Mathieson, Save the Children

The ICRC was allocated about 5 per cent of the total budget. This funding rightly recognised ICRC's frontline responsibility within the Red Cross/Crescent movement for delivering assistance in conflict-affected areas.

Most of the remaining funding (about 15 per cent) was allocated to NGOs and the Australian Red Cross Society through two separate mechanisms: the Humanitarian Partnership Agreement (HPA) and the Dollar for Dollar Initiative (Table 5). In this diversification, Australia sought added value beyond UN programming. These investments also demonstrate a long-term interest in sustaining the reach and credibility of Australian NGOs.

The HPA is an agreement between the Australian aid program and a preselected group of six Australian NGOs with significant global reach and capacity. The Dollar for Dollar Initiative was developed through discussions between Australian NGOs and the Australian aid program. In this initiative, the Australian Government matched the funds donated by the public to 19 NGOs and the Australian Red Cross Society over a specified period. The initiative aimed to raise funds for the crisis and to build public support.

Conclusions

- Australian funding was heavily focused on UN agencies (about 80 per cent), particularly WFP, which received about half the total funds. Other UN agencies funded included CHF, FAO, UNICEF and UNHCR.

- Funds were also allocated to ICRC (5 per cent) and NGOs (15 per cent).

Table 5 Financial allocations to partners, 2011

|

Agency |

HPA funding ($) |

Dollar for Dollar Initiative funding ($) |

Total ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

UN World Food Programme |

57 000 000 |

||

|

UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) |

15 000 000 |

||

|

UN Common Humanitarian Fund |

3 000 000 |

||

|

UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) |

10 000 000 |

||

|

UN Food and Agriculture Organization |

2 000 000 |

||

|

International Committee of the Red Cross |

5 000 000 |

||

|

Australian Red Cross Society |

636 624 |

636 624 |

|

|

Save the Children Australia |

1 500 000 |

1 500 859 |

4 163 859 |

|

World Vision Australia |

455 000 |

1 715 338 |

2 170 338 |

|

Oxfam Australia |

800 000 |

1 143 770 |

1 943 770 |

|

Caritas Australia |

455 000 |

1 386 107 |

1 841 107 |

|

CARE Australia |

990 000 |

487 915 |

1 477 915 |

|

Adventist Development and Relief Agency |

1 130 984 |

1 130 984 |

|

|

PLAN Australia |

800 000 |

258 750 |

1 058 750 |

|

Australian Committee for UNICEF |

1 046 872 |

1 046 872 |

|

|

UN Department for Safety and Security |

500 000 |

||

|

Australian Lutheran World Service |

810 875 |

810 875 |

|

|

Australia for UNHCR |

704 248 |

704 248 |

|

|

Tear Australia |

670 551 |

670 551 |

|

|

Archbishop of Sydney's Overseas Relief and Aid Fund |

520 341 |

520 341 |

|

|

ChildFund Australia |

417 490 |

417 490 |

|

|

CBM Australia |

353 989 |

353 989 |

|

|

National Council of Churches Australia Ltd |

229 090 |

229 090 |

|

|

Baptist World Aid Australia |

222 539 |

222 539 |

|

|

Uniting Church Overseas Aid (Uniting World) |

171 333 |

171 333 |

|

|

Anglican Board of Mission Australia |

91 333 |

91 333 |

|

|

Anglicord |

84 183 |

84 183 |

|

|

Total |

5 000 000 |

13 583 191 |

112 246 191 |

HPA = Humanitarian Partnership Agreement; UN = United Nations

3.5 Timeliness of funding for United Nations agencies and the International Committee of the Red Cross

Following the declaration of famine, Australia was one of the first donors to commit funding. A series of announcements of funding packages were made:

- $8 million on 13 July 2011: this includes grants made before the declaration (Table 4) and an additional $2 million for FAO

- $25 million on 20 July 2011 (coinciding with the famine declaration): $15 million for the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) regionally, $10 million for WFP Ethiopia

- $42 million on 25 July 2011 (coinciding with the Foreign Minister's trip to Somalia): for WFP with $33 million for Somalia and $9 million for Kenya (with $22 million of this coming from an annual contribution to WFP centrally, which was allocated by WFP themselves)

- $15.5 million in August and September 2011: $10 million for the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), $5 million for the ICRC and $0.5 million for the UN Department for Safety and Security.

This timing was similar to other, much bigger donors in the region such as the United Kingdom.24

Several agencies interviewed stated that Australia was among the fastest to pay, with funds arriving within two weeks of pledges being made.25 This is faster than the European Community Humanitarian Office and CHF, which took 92 and 107 days, respectively, on average to disburse their allocations.26

Conclusions

- After the declaration of famine, Australia responded quickly and was among the first donors to commit significant levels of funding.

- Once funds were committed, Australia disbursed funding quickly.

3.6 Timeliness of funding for non-government organisations

Funds were allocated to Australian NGOs through the HPA and Dollar for Dollar Initiative. The HPA was designed as a mechanism to facilitate speedy disbursal of funds in response to rapid-onset crises. When a disaster strikes, an envelope of funding is allocated, and the NGOs included in the agreement rapidly meet, decide who is best placed to respond and submit a proposal. The agreement specifies that funds are to be approved within 48Â72 hours and released within seven days. At the time of the HoA crisis, the HPA had only recently been established. The first activation of the HPA was an allocation of $5 million to the HoA crisis on 20 July. This allocation was split between the agencies according to internal agreement.

The Dollar for Dollar Initiative began in November 2011 and raised $13.5 million from the public, which was matched by the same amount by the Australian Government. Funds from this initiative went to HPA agencies and many other NGOs. The timing of the appeal meant that much of the funding went to 'early recovery' work.

Conclusions

- Funding of NGOs through the HPA was efficient and timely.

- Funding from the Dollar for Dollar Initiative was not available to NGOs until many months after the declaration of famine.

3.7 Country allocations

Somalia received the bulk of Australian assistance. Of total Australian support for the crisis, some $61 million went to Somalia, with lesser amounts of $14 million going to Ethiopia and $37 million to Kenya including the $15 million regional refugee contribution provided to UNHCR (as it all went to Dadaab). Funding to UN agencies followed this pattern (Figure 4). All funding to ICRC was used for Somalia. In contrast, proportionally more funding to NGOs was used in in both Kenya and Ethiopia.

Conclusions

- Australian assistance and allocations to UN agencies were appropriately concentrated on Somalia.

- Funding to NGOs was used in all three countries.

Figure 4 Australian financial assistance, by type of agency and country

ICRC= International Red Crescent Society; NGO = non-government organisation; UN = United Nations

3.8 Funding by sector and form of assistance

Australian assistance was focused on food and nutrition (60 per cent) and refugee support (12 per cent) as intended, but funding also went to many other sectors (Figure 5). Other sectors that were well funded included livelihoods, and water, sanitation and hygiene. Smaller amounts of funding were used for education, health, shelter and non-food items, and protection.

The sectors and type of assistance funded by UN and ICRC investments follow this general pattern, while NGO support was somewhat different (Figure 5). Proportionately, significantly less NGO funding was used for food (12 per cent) and displaced people, and much more for water, sanitation and hygiene (33 per cent), and livelihoods (24 per cent). Many of the sectors, including health and education, which received a low level of support from UN agencies, received proportionately more funding from NGOs funded by the Dollar for Dollar Initiative. Consequently, the sectoral spread of Australian assistance stems from NGO funding.

While Australia funded some cash transfer programs, they were only about 2 per cent of the overall budget. These were funded through grants to UNICEF, the OCHA-managed CHF, the HPA and later through the Dollar for Dollar Initiative. In comparison with UN agencies, NGOs allocated proportionally more funding to cash transfers. Notably, about 13 per cent of the HPA allocation was used for cash transfers.

Conclusions

- Australian assistance and allocations to UN agencies and ICRC were mostly focused on food and nutrition, and refugees, with less funding allocated to other sectors.

- Most funding allocated to NGOs were allocated to water, sanitation and hygiene, and livelihoods.

- Funding to NGOs increased the spread of funds across sectors.

- Only a small proportion of funding was used for cash transfers.

Figure 5 Funding allocations to sectors and forms of assistance

NFI = non-food items; WASH = water, sanitation and hygiene

Footnotes

d The September 2010 'special brief' issue of the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit bulletin makes it abundantly clear there is a crisis in south-central Somalia. Subsequent issues document the worsening situation.

References

15 See, for instance, S Levine et al., 2011.

16 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine & John Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2013.

17 See, for instance, Save the Children & Oxfam, A dangerous delayÂthe cost of late response to early warnings in the 2011 drought in the Horn of Africa, Joint Agency Briefing Paper, Boston, 2012.

18 Interviews for this evaluation.

19 J Darcy et al., 2012.

20 See, for instance, C Cabot-Venton, C Fitzgibbon, T Shitarek, L Coulter and O Dooley, The economics of early response and disaster resilience: lessons from Kenya and Ethiopia, Department for International Development, London, 2012.

21 J Darcy, et al., 2012.

22 UK Department for International Development, Humanitarian emergency response in the Horn of Africa, Report 14, Independent Commission for Aid Impact, London, 2012.

23 Interviews for this evaluation.

24 UK Department for International Development, 2012.

25 Evaluation interviews with HPA agencies and WFP.

26 G Taylor, B Willets-King & K Barber, Process review of the Somalia common humanitarian fund, Humanitarian Outcomes, New York, 2012.