Last Updated: 12 December 2024

The Sanctions Compliance Toolkit is produced by the Australian Sanctions Office (ASO) within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). It provides a summary of relevant sanctions laws but does not cover all possible sanctions risks. Users should consider all applicable sanctions measures and seek independent legal advice when considering sanctions compliance risks. This document should only be used as a guide and should not be used as a substitute for legal advice. Users are responsible for ensuring compliance with sanctions laws.

Overview

The Sanctions Compliance Toolkit provides a comprehensive guide aimed at helping regulated entities and legal professionals navigate the complexities of Australian sanctions laws. It offers a structured approach to compliance by outlining key principles, risk management strategies, and best practices that regulated entities can adopt to help ensure they do not contravene sanctions.

The toolkit is divided into two parts. Part One provides a high-level overview of how to identify sanctions risks. This part explains the legal frameworks and the various activities which can be subject to sanctions prohibitions.

Part Two of the toolkit provides an overview of how regulated entities can manage sanctions risks. This part explores the core components of sanctions compliance at the organisational and activity-based levels, with a particular emphasis on how regulated entities can take reasonable precautions and exercise due diligence to avoid sanctions contraventions.

The toolkit is designed to be practical, offering actionable steps for identifying, assessing, and mitigating sanctions risks in various operational contexts. The document provides case studies and examples to illustrate common challenges and how they can be addressed.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Arms or related matériel | Arms or related matériel generally includes weapons, ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, spare parts and accessories for any of those things, and paramilitary equipment. |

| Australian Sanctions Office | The Australian Sanctions Office (ASO) is the Australian Government's sanctions regulator. The ASO sits within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). |

| Consolidated List | See Designated person or entity. |

| Controlled asset | Generally an asset owned or controlled by a designated person or entity. Some sanctions legislation also refers to these kinds of assets as 'freezable assets'. |

| Defence and Strategic Goods List | The Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL) is the list that specifies the goods, software and technology that are regulated under Australian export control legislation. |

| Defence Export Controls | Defence Export Controls (DEC) regulates the export and supply of military and dual-use goods and technologies. See DEC website for further information. |

| Designated person or entity | A person or entity listed under Australian sanctions laws. Listed persons and entities are subject to targeted financial sanctions. Listed persons may also be subject to travel bans. See DFAT website for further information. Some sanctions legislation also refers to these persons or entities as 'proscribed persons or entities'. DFAT keeps a Consolidated List of designated persons and entities, available on the Department's website. |

| Import sanctioned good | A good designated as an 'import sanctioned good' for a specific country or region. |

| Export sanctioned good | A good designated as an 'export sanctioned good' for a specific country or region. |

| Pax | Pax is the Australian sanctions platform. You can make general enquiries or submit sanctions permit applications to the ASO in Pax. |

| Reasonable precautions and due diligence | In the sanctions context, reasonable precautions and due diligence are not defined terms but generally refer to the steps and measures a regulated entity must take to ensure it is not engaging in sanctioned activities. This includes implementing robust internal controls, screening transactions and parties against the Consolidated List, and ensuring staff are adequately trained to recognise and respond to potential sanctions risks. This is a relative standard, as what constitutes 'reasonable' can vary based on a range of factors, including the size and nature of the business, the complexity of transactions, the geographic areas involved, and the specific sanctions regulations in place. Consequently, what is deemed sufficient for one entity may not be for another, making the concept inherently flexible and context dependent. |

| Regulated entity | A government agency, individual, business or other organisation whose activities are subject to Australian sanctions laws. |

| Risk assessment | A sanctions compliance risk assessment is a systematic evaluation of an organisation's exposure to potential sanctions contraventions. This process identifies and analyses the risks associated with a particular activity to determine where sanctions risks may arise. |

| Sanctions permit | A sanctions permit is authorisation from the Minister for Foreign Affairs (or the Minister's delegate) to undertake an activity that would otherwise be prohibited by an Australian sanctions law. |

Part one - Identifying sanctions risks

Australian sanctions

What are sanctions?

Sanctions are measures not involving the use of armed force that are imposed in response to a situation of international concern. They aim to bring a situation of international concern to an end, influence or penalise those responsible, mitigate adverse effects, or resolve international issues.

Australia implements two types of sanctions frameworks under Australian sanctions laws:

- United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions frameworks, which Australia must impose as a member of the United Nations

- Australian autonomous sanctions frameworks, which are imposed as a matter of Australian foreign policy.

In response to a situation of international concern, Australia and/or the UNSC may impose what is referred to as a sanctions 'framework', named after the affected country or group (e.g. 'Iran sanctions') or thematic concern. Each sanctions framework imposes specific sanctions measures, depending on the individual circumstances and objectives of the framework. Australia regularly updates and implements these frameworks shown below.

Sanctions prohibitions

Different sanctions frameworks impose different sanctions measures.

The Charter of the United Nations Act 1945 (Cth), the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 (Cth) and their regulations use common terms to describe sanctions measures.

These sanctions measures generally prohibit two categories of activity:

- Activities associated with designated persons and entities (Targeted Financial Sanctions)

- Activities associated with sanctioned countries, regions or terrorist groups.

Sanctions measures on designated persons or entities are often referred to as Targeted Financial Sanctions (TFS). TFS generally prohibit directly or indirectly making assets available to, or for the benefit of, designated persons or entities. They may also generally prohibit using or dealing with certain assets owned or controlled by them, effectively freezing these assets. Broader restrictions on dealing with assets may apply under certain frameworks. Individuals who are subject to TFS may also be subject to travel bans.

Sanctions measures on sanctioned countries, regions or terrorist groups restrict trade in certain goods, services and commercial activities with those countries, regions or terrorist groups. These measures generally prohibit the export and/or import of certain goods, the provision of certain services, and engaging in certain commercial activities in connection with specific countries, regions or terrorist groups (or certain persons or entities in those places in some cases).

The above two categories are not exhaustive, as some frameworks have other measures that are highly tailored to the framework. These include restrictions regarding vessels under the Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) and Libya sanctions, dealing with assets of Saddam Hussein's regime, and handling cultural property illegally removed from Iraq and Syria.

Penalties for sanctions offences

Sanctions offences are punishable by:

- For an individual - up to 10 years in prison and/or a fine of 2500 penalty units ($825,000 as of 7 November 2024) or three times the value of the transaction(s) (whichever is the greater).

- For a body corporate – a fine of up to 10,000 penalty units ($3.3 million as of 7 November 2024 or three times the value of the transaction(s) (whichever is the greater).

Australian sanctions laws apply broadly, including to activities in Australia, and to activities by Australian citizens and Australian-registered body corporates overseas.

Activities associated with designated persons and entities (Targeted Financial Sanctions)

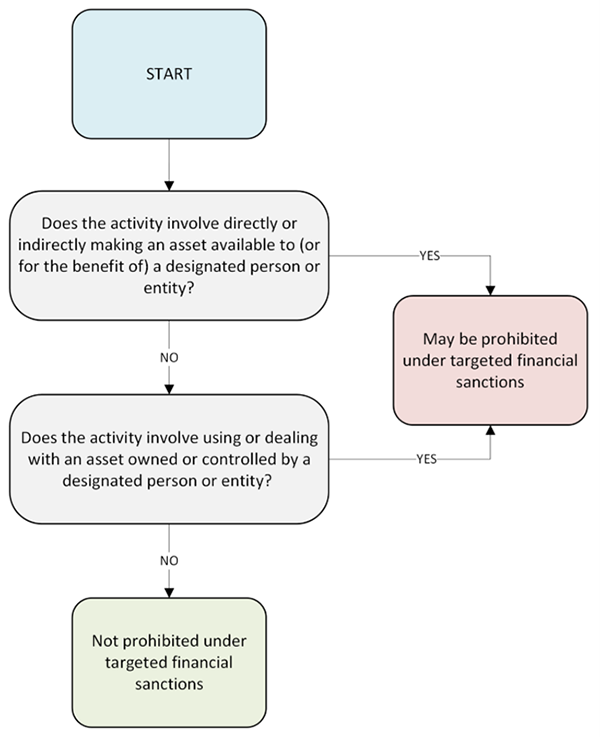

Targeted financial sanctions generally prohibit:

- directly or indirectly making an asset available to (or for the benefit of) a designated person or entity;

- an asset-holder using or dealing (or allowing or facilitating the use or dealing) with an asset that is owned or controlled by a designated person or entity. As these assets cannot be used or dealt with, they are referred to by the ASO as 'frozen'.

Unlike trade restrictions which usually apply to specific goods and services, targeted financial sanctions prohibit the supply of any asset whatsoever to designated persons or entities. An 'asset' includes an asset or property of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable.

The designated persons and entities on which targeted financial sanctions have been imposed are identified on the Consolidated List.

Beneficial ownership

Beneficial ownership refers to the individuals or entities that ultimately own, control, or benefit from assets or transactions, despite being hidden behind layers of corporate structures or intermediaries.

A person can mitigate the risk of indirectly providing funds to a designated person or entity by conducting thorough due diligence and implementing robust know-your-customer procedures to verify the ultimate beneficial owners of their counterparties. These procedures are critical to ensure that a transaction does not indirectly benefit a designated person or entity through a beneficial ownership arrangement.

Case Study: Making an asset directly or indirectly available to (or for the benefit of) a designated person or entity

An Australian import-export company plans to send a payment to a new supplier. The company conducts an initial screening of the supplier against the Consolidated List. While no immediate matches are identified, the company has robust sanctions compliance procedures in place which require due diligence on investigating and verifying the background of its suppliers.

The Australian company further investigates the ownership structure of the supplier and discovers it is wholly owned by a holding company, which in turn is owned by a designated person. Further due diligence confirms that the person has beneficial ownership of the supplier. This indicates that any payment made to the supplier is likely to benefit the designated person. The company concludes that proceeding with the payment would contravene the prohibition on directly or indirectly making an asset available to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity.

Case Study: Using or dealing with an asset that is owned or controlled by a designated person or entity

An Australian brokerage firm manages shares in a company on behalf of a designated person. The designated person retains ownership and control over the shares, including the right to sell them or receive dividends, but the brokerage firm continues to hold the shares on behalf of the designated person. As the shares are owned or controlled by the designated person the brokerage firm may not use or deal with the shares (or any dividends received in respect of them) or allow or facilitate any use or dealing with the shares. The shares and any dividends are, in effect, frozen.

Activities associated with sanctioned countries, regions or terrorist groups

Sanctions on activities associated with sanctioned countries, regions or terrorist groups generally include restrictions on the export and/or import of certain goods, the provision of certain services, and engaging in certain commercial activities. The restrictions typically apply to the country or region subject to the sanctions measure. However, trade restrictions may also apply to specific individuals, groups or entities. For example, counter-terrorism sanctions prohibit the export of goods or the provision of services to members of designated (named) terrorist groups, wherever they may be. These individual, groups or entities are also designated and therefore also captured under TFS restrictions.

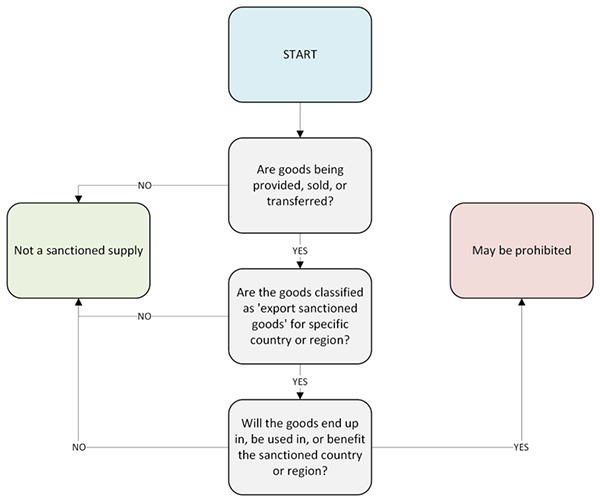

Sanctioned supply

A person generally makes a sanctioned supply if they supply, sell, or transfer goods to another person, and those goods are designated as 'export sanctioned goods' for a specific country, region or terrorist group. If, as a direct or indirect result of the supply, sale or transfer, the goods are transferred to that country, region or terrorist group, for use there or by, or for the benefit of that country, region or terrorist group, the supply is likely to be considered sanctioned.

What constitutes an 'export sanctioned good' varies by sanctions framework, as each framework has specific regulations that define which goods are prohibited from being supplied to that particular country, region or terrorist group.

It is important to understand that supplying, selling, or transferring 'export sanctioned goods' to the relevant country, region or terrorist group is still prohibited, even if those goods were not manufactured in or did not otherwise originate from Australia. Furthermore, the prohibition on making a sanctioned supply applies even when no payment or other financial gain is derived from the provision or transfer of the goods.

Case Study: Sanctioned supply

An Australian company plans to sell goods to a customer in Country X. The company confirms that the customer is not a designated or proscribed entity and is not linked to any such entities. However, the company is aware that Country X is subject to Australian sanctions. The company confirms that the goods are classified as an 'export sanctioned good' for Country X under relevant regulations. It also confirms that the goods would be shipped to the customer in Country X. Therefore, exporting the goods to the customer in Country X would contravene the prohibition on making a 'sanctioned supply'.

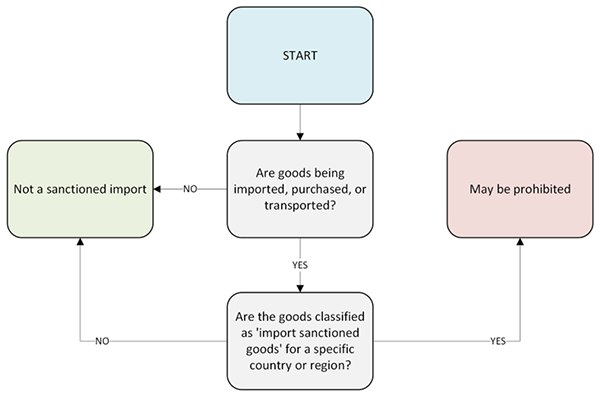

Sanctioned import

A person generally makes a sanctioned import if they import or purchase goods from another person, or transport goods that are designated as 'import sanctioned goods' for a specific country, region or terrorist group, and these goods have been exported from or originate in or from the relevant sanctioned country, region or terrorist group. What constitutes an 'import sanctioned good' varies between frameworks.

It is important to understand that the prohibition on making a 'sanctioned import' can apply to the import or purchase or transport of 'import sanctioned goods' in jurisdictions outside of Australia. Hence, the prohibition does not only apply to the physical import of 'import sanctioned goods' into Australia.

Case Study: Sanctioned import

An Australian company plans to purchase and transport goods from a supplier in Country X. The company confirms that the supplier is not a designated or proscribed entity and is not linked to any such entities. Although Country X is not subject to Australian sanctions, the Australian company is aware that the goods were previously imported by the supplier from Country Y, a country subject to Australian sanctions. The goods are classified as 'import sanctioned goods' for Country Y under relevant regulations. Therefore, purchasing and transporting the goods from the supplier in Country X would contravene the prohibition on making a 'sanctioned import'.

Sanctioned commercial activities

Restrictions are imposed on certain commercial activities involving a sanctioned country or region. There is no general definition of a sanctioned commercial activity. Instead, sanctioned commercial activities tend to be bespoke and context-dependent, relating to specific activities described in the regulations for the relevant sanctions framework. For example, a sanctioned commercial activity for the DPRK includes a person concluding an agreement on behalf of a DPRK domiciled financial institution related to that entity opening an office, branch or subsidiary in Australia.

Case Study: Sanctioned commercial activity

An Australian company plans to acquire shares in a multinational company involved in the construction of a new power plant in Country X. The company confirms that the multinational is not a designated or proscribed entity and is not linked to any such entities. However, the company is aware that Country X is subject to Australian sanctions, some of which are targeted at the construction or installation of new power plants for electricity production in Country X. This commercial activity is described as a 'sanctioned commercial activity' for Country X under relevant regulations. Therefore, acquiring the shares in the multinational company would contravene the prohibition on engaging in a 'sanctioned commercial activity'.

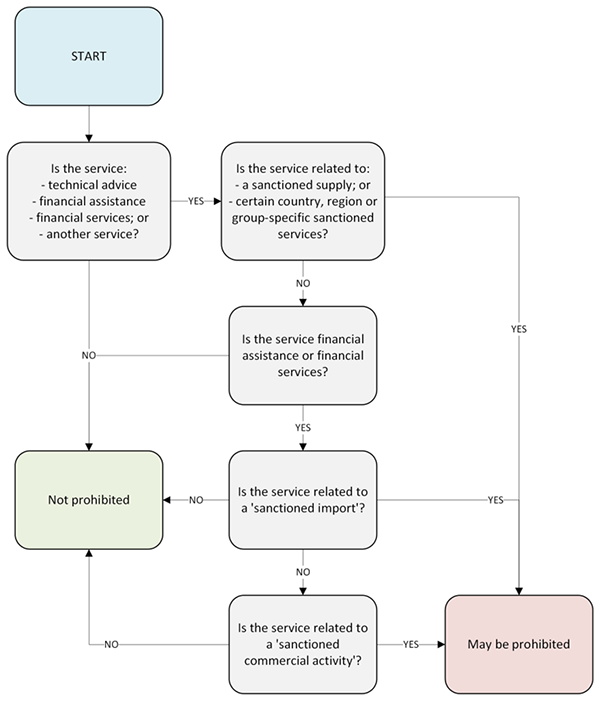

Sanctioned service

A person generally provides a sanctioned service if they provide technical, financial, or other services in connection with a sanctioned supply, import, commercial activity, or certain country-specific activities.

It is generally prohibited to provide:

- technical advice, assistance or training, financial assistance, financial services, or another service if it assists with or is provided in relation to a sanctioned supply or certain country-specific services

- financial assistance or a financial service if it assists with or is provided in relation to a sanctioned import

- an investment service if it assists with or is provided in relation to a sanctioned commercial activity

- a sanctioned service to a designated terrorist group (ISIL (Da'esh), Al Qaida, the Taliban and Al-Shabaab).

Just like sanctioned commercial activities, some sanctioned services can be bespoke and context-dependent, relating to specific activities described in the regulations for the relevant sanctions framework. For example, a sanctioned service for the DPRK includes engaging in sanctioned scientific or technical cooperation with persons sponsored by or representing the DPRK.

Case Study: Providing a sanctioned service

An Australian finance firm is proposing to provide a loan to an Australian export company to finance the export of goods to Country X. The firm is aware that Country X is subject to Australian sanctions. The firm confirms that the goods to be exported are classified as 'export sanctioned goods' for Country X under relevant regulations, and the supply of these goods would contravene the prohibition on making a 'sanctioned supply'. Therefore, providing a financial service to the Australian export company that would assist with or is provided in relation to the sanctioned supply is prohibited as it would constitute providing a sanctioned service.

Other sanctions measures

Restrictions regarding vessels

Australia imposes sanctions against vessels under the DPRK and Libya sanctions frameworks. The prohibitions restrict a range of services and activities involving certain designated vessels. It is open for Australia to impose sanctions under other frameworks – please consult the consolidated list for current sanctions.

Using or dealing with assets of Saddam Hussein's regime

The Iraq sanctions framework imposes restrictions on using or dealing with assets that were formerly owned by Saddam Hussein's regime, or assets that were acquired, or removed from Iraq, by persons or entities that have been designated by the UNSC.

Restrictions on dealing with cultural property illegally removed from Iraq and Syria

Australia's sanctions regimes for Iraq and Syria aim to protect cultural property illegally removed from these countries. Under the Iraq sanctions, items removed on or after 6 August 1990 that are Iraqi cultural property or of archaeological, historical, cultural, rare scientific, or religious importance are protected. Similarly, under the Syria sanctions, items removed on or after 15 March 2011 with the same criteria are protected. It is prohibited to trade, transfer, or give such items to another person.

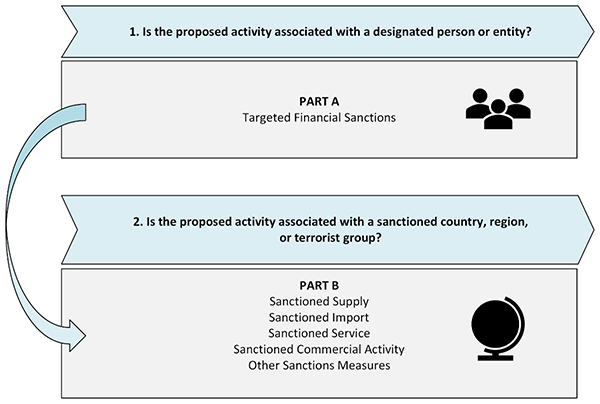

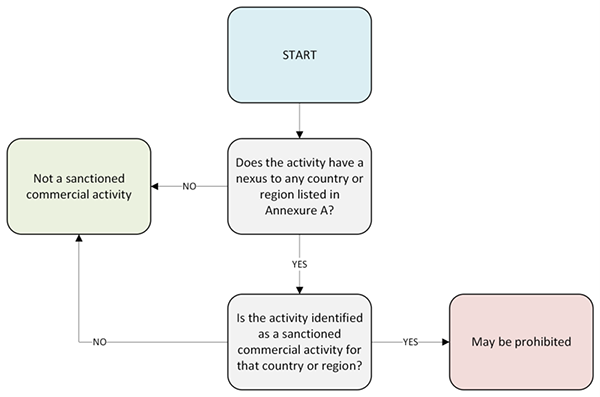

A structured approach to identifying sanctions risks

Regulated entities can assess any given activity against Australian sanctions prohibitions by the following a structured approach to determine if the activity has a connection to any sanctioned person, entity or country.

A structured sanctions assessment generally consists of two components:

Given the broad remit of targeted financial sanctions, assessing these risks should be the priority, as any connection between the activity and a designated person or entity raises significant sanctions compliance risks. This assessment includes:

- checking if the activity involves directly or indirectly making assets available to, or for the benefit of, a person or entity identified in the Consolidated List

- checking if the activity involves using or dealing with assets owned or controlled by a person or entity identified in the Consolidated List.

If no such connections can be identified, the focus should then turn to assessing whether the activity has any relevant nexus to a country or region under Australian or UNSC sanctions. If such a connection can be established a systematic assessment of each of the relevant sanctions prohibitions should be conducted. This assessment includes:

- confirming if the activity involves the export or import of sanctioned goods or the provision of sanctioned services;

- verifying if the activity constitutes a sanctioned commercial activity;

- consulting relevant sanctions frameworks for any other country-specific prohibitions and measures; and

- assessing if the activity involves prohibited dealings with cultural property, restricted vessels, or assets of former regimes (e.g. Saddam Hussein's regime).

Regulated entities can refer to the ASO's Sanctions Risk Assessment (SRA) for assistance in making this assessment. The SRA is available on the DFAT website.

The SRA is a structured questionnaire which can be used by regulated entities to inform a preliminary assessment of the sanctions risks associated with a given activity and follows the structure identified above.

It is important to note that the SRA is not a substitute for comprehensive analysis and independent advice regarding sanctions compliance risks. The responsibility for identifying and managing sanctions risks rests solely with regulated entities.

Independent legal advice

Independent legal advice can be invaluable in accurately identifying sanctions risks. Legal experts can offer tailored guidance that takes into account the specific circumstances of your organisation, including its industry, geographic scope, and the nature of its activities.

Legal professionals can help interpret complex sanctions regulations and identify potential risks associated with your activities. They can also provide clarity on ambiguous or evolving aspects of sanctions laws.

Moreover, legal advisors can assist in documenting the steps taken to identify sanctions risks. This documentation is essential for demonstrating your organisation's due diligence, which can be crucial if your organisation needs to justify its actions to the ASO or in the context of legal proceedings.

Part two – Managing sanctions risks

Risk in sanctions compliance

Sanctions compliance is complex and challenging due to the constantly changing regulations and wide range of activities that can trigger contravention risks. It may not be possible to fully mitigate sanctions risks in every case, as even low-risk activities like exporting goods or dealing with overseas entities could involve designated parties or indirect links to sanctioned individuals or countries, making it hard to avoid all potential contraventions.

The constantly changing nature of sanctions laws adds complexity. Australian sanctions are frequently updated, with new designated persons or entities and changes to specific measures. This requires regulated entities to continuously monitor and update their compliance programs to stay current with the latest regulations.

Given these challenges, the focus for regulated entities shifts from attempting to eliminate all sanctions risks—an often-unattainable goal—to managing those risks as effectively as possible. This involves taking reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence to avoid contraventions. This means implementing robust internal policies, procedures, and controls that are tailored to the specific risks faced by the business. For example, regulated entities should regularly screen transactions, customers, and partners for links to sanctioned entities, ensure staff are well-trained, and keep their compliance programs updated and regularly audited.

It is a defence to a strict liability offence if a body corporate demonstrates it took reasonable precautions and exercised due diligence to avoid contravening the sanctions law. However, what is objectively 'reasonable' is highly context-dependent and can vary based on factors such as the size and nature of the business, the complexity of its transactions, and the specific geographic regions and sanctions regulations involved.

Strict liability

Sanctions offences are strict liability offences for bodies corporate (including corporate government agencies), meaning that it is not necessary to prove any fault element (intent, knowledge, recklessness or negligence). However, bodies corporate can prove that they undertook reasonable precautions and exercised due diligence to avoid contravening sanctions laws as a defence.

Risk mitigation - organisational compliance

The steps a regulated entity can take to mitigate sanctions compliance risk can be broadly categorised into organisational compliance and activity-based compliance measures.

Organisational compliance involves the establishment and maintenance of internal policies, procedures, and controls within a regulated entity to ensure adherence to relevant sanctions laws. This includes regular staff training, risk assessments, and audits to verify compliance. An excellent example of organisational compliance in practice is the establishment and maintenance of a Sanctions Compliance Program (discussed in more detail below).

Activity-based compliance focuses on the specific actions and transactions carried out by a regulated entity. This includes monitoring and screening individual transactions, customers, and business partners to ensure they do not involve sanctioned entities or contravene sanctions. Reasonable precautions and due diligence, and sanctions permits form a subset of activity-based compliance and are discussed in more detail below.

Sanctions Compliance Programs

Sanctions Compliance Programs and risk assessments play a central role in sanctions compliance at the organisational level.

A Sanctions Compliance Program (SCP) is a set of tailored policies, procedures, and controls designed to help a regulated entity to comply with Australian sanctions laws. The program should always be tailored to the specific risks and activities of the entity, but it should typically include the following elements:

- Senior management commitment: The highest levels of management within a regulated entity must be committed to sanctions compliance and must provide the necessary resources to support the program.

- Risk assessments: The regulated entity must continually assess its exposure to sanctions risks, both in terms of its products and services, its customers and suppliers, and its geographic reach (see Risk assessments below).

- A screening program: The regulated entity should implement a screening program to continually identify and assess its exposure to sanctions risks. This includes screening customers, transactions, and third-party service providers for potential sanctions contraventions.

- Training: The regulated entity should provide ongoing training to its employees on sanctions compliance requirements. This training should cover the entity's sanctions policies and procedures, as well as the risks of sanctions contraventions.

- Monitoring and enforcement: The regulated entity should implement a monitoring and enforcement program to ensure that its SCP is effective. This includes reviewing reports and alerts, conducting audits, and taking corrective action when necessary.

- Auditing: The regulated entity should have its SCP audited by an independent party on a regular basis.

In addition to these core elements, regulated entities should also consider implementing additional measures, such as:

- Establishment of a sanctions compliance committee: A sanctions compliance committee can provide oversight of the SCP and help to ensure that it is effective.

- Foster a culture of compliance: The regulated entity should foster a culture of sanctions compliance within the organisation by promoting awareness of sanctions risks and emphasising the importance of compliance.

The design of a SCP is an ongoing process that should be reviewed and updated on a regular basis. A well-designed SCP can help a regulated entity to avoid the serious penalties and reputational harm which can accompany sanctions contraventions.

Risk assessments

Risk plays a critical role in sanctions compliance. By understanding the risks that a regulated entity faces at an organisational level, it can develop a more effective SCP. The risks a regulated entity faces are relative to the nature of its activities. For example, a company exporting dual-use goods is likely to face different risks than those faced by a university providing research facilities to foreign students.

Some of the key risks that a body corporate can face include:

- Direct exposure to sanctioned countries, persons and entities: This is the most obvious risk, and it is one most people think of when they hear the term 'sanctions risk'.

- Indirect exposure to sanctioned persons or entities: This can occur through a variety of channels, such as doing business with a company that is owned or controlled by a designated person or entity.

- Failure to properly screen customers and transactions: This can lead to inadvertent violations of sanctions, even if a regulated entity is not directly exposed to sanctioned parties.

- Inadequate training for employees: Employees who are not properly trained on sanctions compliance are more likely to make mistakes that could lead to contraventions.

Risk mitigation – activity-based compliance

Reasonable precautions and due diligence are the guiding principles for a body corporate to manage its exposure to sanctions compliance risk in the context of specific activities.

In the sanctions context, reasonable precautions and due diligence are not defined terms but generally refer to the steps and measures a regulated entity should take to avoid engaging in sanctioned activities.

Case studies

The following case studies provide examples of reasonable precautions and due diligence that can be undertaken in the context of certain activities. It is important to note that this is a relative standard, as what is objectively 'reasonable' can vary based on a range of factors, including the size and nature of the business, the complexity of transactions, the geographic areas involved, and the specific sanctions regulations in place. Consequently, what is deemed sufficient for one entity may not be for another, making the concept inherently flexible and context dependent. The following examples are provided as a guide only.

Case study: Making payments to persons or entities

ABC Boutique is a retail business in Australia specialising in home decor items. The business must comply with Australian sanctions laws and should take reasonable precautions and exercise due diligence to avoid contravening sanctions laws.

ABC Boutique plans to make a payment to XYZ Enterprises, a new overseas supplier, for an order of merchandise. The boutique is aware of the need to avoid the direct or indirect provision of assets to designated persons or entities on the Consolidated List.

The boutique takes the following steps in accordance with its sanctions compliance program to avoid contravening sanctions:

- The boutique reviews the DFAT website for any relevant sanctions compliance material related to the country XYZ Enterprises operates in. This includes checking for updates on sanctions regulations and any additional guidance provided by the ASO.

- The boutique performs a check on XYZ Enterprises against the Consolidated List available on the DFAT website. This preliminary step ensures that the recipient is not listed as a designated person or entity.

- The boutique evaluates the risk associated with the payment by reviewing the details of XYZ Enterprises, such as the country it operates in and any known connections. This helps in assessing whether the payment might inadvertently involve a sanctioned party.

- The boutique requests additional details from XYZ Enterprises, including its registration information and ownership structure. Any intermediate holding companies or ultimate beneficial owners are checked against the Consolidated List. This helps confirm that the supplier is not linked to any designated persons or entities.

- If any initial checks or additional information raise concerns about potential links to designated parties, the boutique is prepared to hold the payment temporarily and seek further clarification or advice before proceeding.

- The boutique obtains independent legal advice which provides guidance on the necessary steps to verify that the payment complies with Australian sanctions laws.

- The boutique maintains detailed records of the steps taken, including the screening process, any legal advice obtained, and communications with XYZ Enterprises. This documentation serves as proof of their due diligence.

After conducting the screening and obtaining independent legal advice, the boutique confirms that XYZ Enterprises is incorporated in a sanctioned country but that it is not associated with any designated persons or entities. It therefore concludes that making the payment will not involve a contravention of a prohibition on making an asset available to a designated person or entity.

Case study: Exporting goods

JKL Solutions is an Australian company which exports renewable energy equipment. The company must comply with Australian sanctions laws and should take reasonable precautions and exercise due diligence to avoid contravening sanctions laws. These laws prohibit supplying, selling, or transferring goods classified as 'export sanctioned goods' to certain countries or regions.

JKL Solutions plans to export a shipment of solar panel systems to EFG Tech, a new customer based in Country Y, which is subject to export sanctions. The company needs to ensure that this shipment does not contravene Australian sanctions laws.

JKL Solutions takes the following steps in accordance with its sanctions compliance program to avoid contravening sanctions:

- The company reviews the DFAT website for any relevant sanctions compliance material related to Country Y. This includes checking for updates on sanctions regulations, specific prohibited goods, and any additional guidance provided by the ASO.

- The company performs a check on EFG Tech against the Consolidated List available on the DFAT website. This confirms that EFG Tech is not listed as a designated person or entity.

- The company evaluates the risk associated with the supply by reviewing the details of EFG Tech, such as the country it operates in and any known connections. This helps in assessing whether the supply of goods might inadvertently involve a sanctioned party.

- The company requests additional details from EFG Tech, including its registration information and ownership structure, and the intended use and end destination of the solar panels. It checks to see whether any related persons or entities are on the Consolidated List. This helps confirm that EFG Tech is not linked to any designated persons or entities and that the goods will not be used in a manner that contravenes sanctions.

- The company examines the regulations for Country Y to determine which goods are classified as 'export sanctioned goods'. This ensures that none of the solar panel systems being shipped are prohibited from export to that country.

- The company obtains independent legal advice on compliance requirements which confirms that the solar panel systems do not fall under the sanctions prohibitions for Country Y.

- The company maintains detailed records of all compliance measures, including screening processes, legal advice received, and communications with EFG Tech. This documentation serves as proof of their due diligence.

- The company establishes a monitoring process to ensure ongoing compliance. If any issues arise or new sanctions are imposed, the company is prepared to reassess the transaction and take necessary actions.

After conducting thorough screening, reviewing DFAT compliance material, consulting with legal advisors, and verifying the goods, the company confirms that EFG Tech is not associated with any designated persons or entities and that the solar panel systems are not classified as 'export sanctioned goods' for Country Y.

Case study: Providing services

BrightTech is an Australian company specialising in advanced IT solutions. The company must adhere to Australian sanctions laws, which prohibit the provision of sanctioned services. This includes prohibitions on providing technical advice, financial assistance, or other support that assist with or are provided in relation to sanctioned supplies, imports, or commercial activities.

BrightTech plans to offer IT consultancy services to TechAdvance, a new client based in Country Z, which is subject to sanctions. TechAdvance has requested technical support for implementing and maintaining a new software system. The company needs to ensure that providing these services does not violate Australian sanctions laws.

BrightTech takes the following steps to avoid contravening sanctions:

- The company reviews the DFAT website for relevant sanctions compliance material related to Country Z. This includes checking for updates on sanctions regulations, specific prohibited services, and any additional guidance from the ASO.

- The company performs a check on TechAdvance against the Consolidated List available on the DFAT website. This confirms that TechAdvance is not listed as a designated person or entity.

- The company examines the specific sanctions regulations for Country Z to understand which services are prohibited. This helps determine if providing IT consultancy services could be considered a sanctioned service under the current regulations.

- The company requests detailed information from TechAdvance, including its registration information and ownership structure, and the intended use of the software system and the nature of the consultancy required. It checks any related persons or entities against the Consolidated List. This helps ensure that TechAdvance is not linked to any designated persons or entities and the services provided are not related to any sanctioned activities.

- The company obtains independent legal advice. The advisor confirms whether providing IT consultancy services to TechAdvance would contravene any sanctions related to Country Z.

- The company maintains detailed records of all compliance measures, including screening processes, legal advice received, and communications with TechAdvance. This documentation serves as proof of their due diligence.

- The company sets up a monitoring process to ensure ongoing compliance. If any issues arise or new sanctions are imposed, the company is prepared to reassess the provision of services and take necessary actions.

After conducting a thorough review, obtaining legal advice, and verifying the nature of the IT consultancy services, BrightTech confirms that providing services to TechAdvance does not contravene sanctions regulations for Country Z.

Sanctions permits

A sanctions permit is authorisation from the Minister for Foreign Affairs (or the Minister's delegate) to undertake an activity that would otherwise be prohibited by an Australian sanctions law.

The Minister may grant permits under both UNSC and autonomous sanctions frameworks. For some countries, both UNSC and autonomous sanctions apply. More detailed information on Australia's sanctions frameworks and the specific criteria for granting permits under each framework can be found on the DFAT website.

The criteria for sanctions permits under UNSC frameworks vary, as do the range of activities that the Minister can authorise. These activities tend to be more limited than those which can be authorised under autonomous sanctions frameworks. Additionally, some of the UNSC frameworks require the Minister to notify or receive the approval of the UNSC before granting a sanctions permit.

Additional authorisations and criteria may apply in respect of the export of goods that are subject to Defence Export Controls (e.g. dual-use goods included on the Defence and Strategic Goods List).

The 'national interest' test

All permits granted under autonomous sanctions frameworks are subject to the same criteria - the Minister must be satisfied that granting the permit is 'in the national interest'.

The 'in the national interest' test requires the Minister to be satisfied that the grant of a permit is beneficial, or advantageous, to the national interest. It requires a consideration of whether something is advantageous to the interest of the nation as a whole, as opposed to a particular company, group or section within the nation, or to a particular region or locality.

When is it appropriate to apply for a sanctions permit?

The ASO advocates for proactive risk management rather than relying on permits. Sanctions permits are generally appropriate only when there is a clear likelihood of a sanctions contravention occurring. For broad or non-specific sanctions risks, it is better to manage compliance through reasonable precautions and due diligence to prevent issues before they arise. To enable due consideration of any permit application, the ASO must be provided sufficient detail of a specific contravention to which the application relates.

Sanctions permits granted by the Minister only authorise activities within specific parameters. A sanctions permit does not authorise any activities falling outside the scope of the permit. For example, a permit may authorise the supply of a good to a specific end user, but if that good is supplied to an alternative end user, even unintentionally, that further supply will not be authorised by the permit and a contravention may still occur.

For these reasons, permits should not be seen as an exhaustive means of mitigating all sanctions compliance risk. Regulated entities should still take reasonable precautions and exercise due diligence to avoid unauthorised contraventions, even in circumstances where a permit has been granted.

Sanctions permits cannot be granted retrospectively to authorise activity which has already contravened sanctions.

Case study: Humanitarian aid

A humanitarian organisation plans to deliver essential medical supplies and food aid to civilians in a war-torn country that is subject to sanctions. The intention of the activity is to alleviate human suffering and prevent a humanitarian crisis.

Despite thorough planning and strict sanctions compliance procedures, the activity attracts unavoidable risks. For example, despite the organisation's efforts to ensure that aid reaches the intended recipients, there is a possibility that the supplies might be diverted by local authorities or armed groups, thus inadvertently providing support to sanctioned persons or entities (Activity A).

For Activity A, as the organisation does not intend to provide supplies directly to sanctioned persons or entities, nor is there a clear likelihood of this occurring unintentionally, a sanctions permit is not the appropriate tool to manage the compliance risk. Rather, the organisation must take reasonable precautions and exercise due diligence to avoid the risk of the supplies being diverted.

However, the same humanitarian organisation may be aware of a real risk of contravening sanctions as part of its plans to deliver aid. For example, in some conflict zones, access to affected civilian populations might be controlled by sanctioned groups or authorities. To deliver aid effectively, the organisation might need to negotiate or make concessions to these groups, which would result in a sanctions contravention. Additionally, the organisation might need to make payments or financial transactions to facilitate the purchase and delivery of essential supplies (Activity B).

In this example, the organisation may apply for a permit for Activity B, whilst also taking reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence to avoid unintentional contraventions resulting from Activity A.

For Activity B, in considering the permit application the Minister may conclude that a sanctions permit is 'in the national interest' because, amongst other considerations, the delivery of aid demonstrates Australia's commitment to promoting regional stability and its ethical responsibility to address humanitarian crises.

The authorisations in any permit for Activity B are likely to be highly specific and may be subject to conditions. For example, the organisation may be authorised to only deliver a particular volume of a type of good to a specific location or end user. Any diversion of the supplies to an alternative and unauthorised end user may result in a contravention irrespective of the existence of the permit.

Case study: Dual-use goods

Sanctions compliance risks are heightened for businesses involved in the export of dual-use goods. Dual-use goods are items, including software and technology, that can be used for both civilian and military applications. These goods have legitimate commercial uses but can also be utilised for military purposes.

A common example of a dual-use good is a GPS device. These devices are commonly used for civilian purposes like navigation in cars, hiking, and personal travel. However, the same GPS technology can also be used for military applications, such as coordinating troop movements, targeting systems for weapons, and reconnaissance missions. Despite their everyday civilian use, the potential military applications make GPS devices a dual-use good.

If a company plans to export GPS technology for civilian use to a country which is subject to a ban on the export of 'arms or related matériel', it must consider the risk that the technology might be redirected to a different end user or repurposed for alternative end-use once it reaches the country. A sanctions permit would not be appropriate for an activity where there is no intention to supply GPS technology for a prohibited (military) use, nor a clear likelihood that it would occur. However, if the activity was to proceed and unintentionally result in the goods being used for a prohibited (military) use the exporting company will contravene sanctions nonetheless.

In these circumstances the company must ensure that it is able to demonstrate that it took reasonable precautions and exercised due diligence to attempt to avoid this occurrence.

Making an application for a sanctions permit

You can make an application for a sanctions permit in the Australian sanctions portal Pax. You will first need to register as a user of Pax before preparing and submitting your application.

Before submitting an application, please read all the information on the DFAT website and get legal advice as appropriate. You should not submit an application for a permit unless you believe your proposed activity is affected by sanctions and it meets the criteria for a permit.

What information is required?

To enable due consideration of any permit application, the ASO must be provided sufficient detail of a specific contravention to which the application relates.

The ASO expects that legal and professional advisers will have fully considered the relevant law and formed a view about an application before approaching ASO for guidance or submitting an application.

Pax will guide you on what additional information you need to provide to submit an application. This includes, for example:

- detailed description of the goods and services involved, including the technical specification for your goods (this information should match any supporting documentation such as Purchase Orders or Defence End Use Statements),

- detailed description of the end use of the goods or services,

- detailed information on the end user and any other relevant parties to the proposed activities including end user certification,

- the intended transport pathway for any goods and services you propose to provide, from you, through any intermediaries, to the end user.

Please ensure that all information on goods and proposed activities is provided in plain English language and any additional information that may be relevant, for example information about potential uses of a good, is included.

You must ensure that the information you provide is accurate and complete. It is a serious criminal offence to give false or misleading information in connection with the administration of Australian sanctions laws. The penalties include up to ten years in prison and substantial fines. A sanctions permit will be treated as never having been granted if false or misleading information was contained in the application for the permit.

The ASO may request further information in order to assess an application. To assist the efficient processing of your application, please answer requests for further information promptly and ensure all requested information is provided.

If a person wants to share information or documents with the ASO without breaching other legal obligations, they can ask the ASO to issue a notice requiring they share that information.

What does the ASO do with the information provided?

The business and financial information you provide to the ASO will be treated as confidential, unless you state otherwise. This information may be used to administer sanctions law in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations Act 1945 (Cth) and the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 (Cth), and in relation to import/export controls. We will not disclose this information to third parties for any other purpose, unless you have provided your consent or we are otherwise authorised to do so by law.

How long does it take to finalise a permit application?

While we work as quickly as possible to process applications, you should allow a minimum of 3 months for the ASO to process your application, especially for complex activities and activities in high-risk countries or regions.

The time it will take to get a response will depend on a range of factors, including:

- the complexity of your application

- whether all relevant information has been provided, including supporting documentation

- whether you respond promptly to any request for further information or documentation

- the time it takes to check the information you have given us

- the time it takes to get information from other Australian Government agencies (if necessary)

- the time it takes to consult the UNSC or other countries where required, for example if an application relates to a UNSC sanction, the Foreign Minister may need to notify or receive the approval of the relevant UNSC sanctions committee

- whether your proposed activity is taking place in a high-risk country or region, which will require a higher degree of risk management

- our current caseload, as high caseloads can cause delays.

The ASO will assess applications on a case-by-case basis. Generally, we work on applications in the order we receive them. However, this does not necessarily mean they will be finalised in the same order. Some applications will take longer than others to process.

The ASO will endeavour to prioritise applications with commercial deadlines, but given the complexity of the relevant considerations, there is often limited scope to reduce the time it takes to finalise the process. The ASO will often need to consult with domestic, and sometimes international partners. The ASO will not recommend the Minister grant a permit unless it has completed the necessary consultation. It is therefore in your interests as an applicant to ensure the ASO has sufficient time to give your application due consideration.

What if I am granted a permit with conditions?

Sanctions permits are often granted with conditions. Any permit conditions will be set out in your permit. It is a serious criminal offence to contravene a condition of a sanctions permit. The penalties include up to ten years in prison for individuals and substantial fines for individuals and bodies corporate. The ASO may monitor your compliance with permit conditions and take compliance action if necessary.

On some occasions, as a condition of the permit the ASO may require that the permit holder prepare a Sanctions Compliance Report addressing specific issues as identified by the ASO. This condition is often included in permits relating to activities where there are residual risks of non-compliance with the terms of the permit and so the ASO can ensure you are continuing to take reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence to avoid unintended contraventions. For example, activities involving the export of dual-use goods where there is a risk of diversion to alternative end-users or end-uses.

How long does a permit last?

The length of time of a permit is decided on a case-by-case basis. While permits are usually issued for a period of 12 months, they can be issued for a longer period where there is a reasonable case. For example, if you can provide details of future orders that would make up a series of transactions with one end-user, it may be possible to process these under one application and issue a single permit for a longer duration. You must provide sufficient detail in the application, including on the final end-user, timing and end-use location/project, as well as the specific goods to be exported.

However, it is important to note that sanctions laws may change during the validity period of the permit. Additionally, a permit can be amended or revoked at the discretion of the Minister, particularly if there has been a change in circumstances or the sanctions laws.

It is your responsibility to ensure you have sufficient terms in your contracts in the event sanctions laws change or the permit is revoked by the Minister. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade will not be liable or responsible for any loss or damage, however described, incurred by permit holders as a result of changes to sanctions laws or the revocation of a permit.

Further information and resources

While this guidance note provides a framework for understanding key sanctions risks and compliance requirements, it is essential to remember that it does not cover every possible scenario. Sanctions compliance is an ongoing obligation rather than a one-time assessment. Sanctions measures and associated risks are constantly evolving, requiring regulated entities to continuously monitor and reassess their compliance strategies. Regulated entities are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their specific situations and ensure thorough due diligence in all activities.

Further information is available on the Department's website and in ASO guidance notes on specific sanctions topics. If you have any questions, you can make an enquiry through Pax.

Annexure A – Sanctions measures on countries, regions or terrorist groups

| Sanctions measures | Dealing with designated persons and entities | Supply, sale or transfer of arms or related materiel | Supply, sale or transfer of certain goods | Import, purchase or transport of certain goods | Sanctioned commercial activities and/or services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yemen (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Sudan (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| South Sudan (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Lebanon (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Iraq (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Democratic Republic of Congo (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Central African Republic (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Al-Shabaab (Somalia) (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | ✖ | ✖ |

| ISIL and Al-Qaida (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| The Taliban (UNSC) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Syria (UNSC/AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

| Libya (UNSC/AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | ✖ | ✖ |

| Iran (UNSC/AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

| Democratic People's Republic of Korea (UNSC/AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

| Myanmar (AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Russia (AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

| Zimbabwe (AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N/A | ✖ |

| Ukraine (AUTONOMOUS) | ✖ | N/A | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ |

Key:

✖ = Applicable

N/A = Not Applicable

This table does not include sanctions frameworks which only apply restrictions on dealing with designated persons and entities. All persons and entities designated under Australian sanctions laws are listed on the Consolidated List.

Restrictions are also imposed on using or dealing with assets of Sadam Hussein's regime and dealing with cultural property. More information is available on the DFAT website.

Restrictions are also imposed on dealing with cultural property illegally removed from Syria. More information is available on the DFAT website.

Annexure B – Flowcharts to identify potential contraventions

Note: It is prohibited to provide certain services to sanctioned terrorist groups, such as ISIL (Da'esh), Al Qaida, the Taliban, and Al-Shabaab.