First published: 6 December 2024 - updated: 12 September 2025

This guidance note is produced by the Australian Sanctions Office (ASO) within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). It provides a summary of relevant sanctions laws but does not cover all possible sanctions risks. Users should consider all applicable sanctions measures and seek independent legal advice. This document should not be used as a substitute for legal advice. Users are responsible for ensuring compliance with sanctions laws.

Overview

Australian sanctions laws can affect various activities conducted by Australian universities, especially when enrolling a student, employing a person, or engaging in research collaborations with persons and entities from sanctioned countries. This guidance note outlines the key sanctions risks for the university sector across these activities and offers guidance on how to comply with Australian sanctions laws.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Australian Sanctions Office | The Australian Sanctions Office (ASO) is the Australian Government's sanctions regulator. The ASO sits within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). |

| Defence and Strategic Goods List | The Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL) is the list that specifies the goods, software and technology that are regulated under Australian export control legislation. |

| Defence Export Controls | Defence Export Controls (DEC) regulates the export and supply of military and dual-use goods and technologies. See DEC website for further information. |

| Designated person or entity | A person or entity listed under Australian sanctions laws. Listed persons and entities are subject to targeted financial sanctions. Listed persons may also be subject to travel bans. Some sanctions legislation also refers to these persons or entities as 'proscribed persons or entities'. DFAT keeps a Consolidated List of designated persons and entities, available on the Department's website. |

| Pax | Pax is the Australian sanctions platform. You can make general enquiries or submit sanctions permit applications to the ASO in Pax. |

| Reasonable precautions and due diligence | In the sanctions context, reasonable precautions and due diligence are not defined terms but generally refer to the steps and measures a regulated entity must take to ensure it is not engaging in sanctioned activities. This includes implementing robust internal controls, screening transactions and parties against the Consolidated List, and ensuring staff are adequately trained to recognise and respond to potential sanctions risks. This is a relative standard, as what constitutes 'reasonable' can vary based on a range of factors, including the size and nature of the business, the complexity of transactions, the geographic areas involved, and the specific sanctions regulations in place. Consequently, what is deemed sufficient for one entity may not be for another, making the concept inherently flexible and context dependent. |

| Regulated entity | A government agency, individual, business or other organisation whose activities are subject to Australian sanctions laws. |

| Risk assessment | A sanctions compliance risk assessment is a systematic evaluation of an organisation's exposure to potential sanctions contraventions. This process identifies and analyses the risks associated with a particular activity to determine where sanctions risks may arise. |

What sanctions measures are most relevant to the university sector?

Australia implements two types of sanctions frameworks under Australian sanctions laws:

- United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions frameworks, which Australia must impose as a member of the United Nations,

- Australian autonomous sanctions frameworks, which are imposed as a matter of Australian foreign policy.

Within each framework, Australian sanctions laws impose a range of sanctions measures that can apply to a wide range of activities. This guidance note highlights two key sanctions measures that are commonly relevant to universities: providing a sanctioned service and dealing with a designated person or entity.

The most common activities affected include:

- enrolling a student from a sanctioned country,

- employing a person from a sanctioned country,

- collaborating with another person or entity (including a foreign university) from a sanctioned country.

Providing a sanctioned service

- Australian sanctions laws impose general restrictions on providing sanctioned services across various sanctions frameworks. Additionally, there are specific restrictions that supplement these general restrictions and apply only to particular sanctions frameworks.

- Under the general restrictions, a 'sanctioned service' may include, but is not limited to:

- technical advice, assistance or training,

- financial assistance,

- a financial service,

- another service,

- if it assists with, or is provided in relation to:

- a 'sanctioned supply',

- a 'military activity'; or

- the manufacture, maintenance or use of 'export sanctioned goods'.

In the context of an Australian university, the prohibition on a 'sanctioned service' will generally apply to:

- the provision of technology related to the manufacture, maintenance or use of 'export sanctioned goods'; or

- the provision of technical advice, assistance or training if it assists with the manufacture or use of an 'export sanctioned good'.

In this context, "technology" includes specific information about the development, design, production, or "use" of an export-sanctioned good. The prohibition may apply if the service is provided to the sanctioned country (e.g., a government entity) or to a person (e.g., a citizen or resident) for use in the sanctioned country. The prohibition on 'technical advice, assistance, or training' also encompasses various types of supervision and training provided by a university to a research student, especially PhD students.

In addition to services related to 'export sanctioned goods', 'sanctioned services' also encompass specific restrictions related to particular countries (or parts of countries) and activities which do not require a nexus to an 'export sanctioned good'.

These country-specific sanctioned services apply to Iran, Myanmar, Russia, Syria, Zimbabwe, DPRK, and specified regions of Ukraine (Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Sevastopol, and regions specified by the Minister). For example, a sanctioned service for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) also includes engaging in sanctioned scientific or technical cooperation with persons sponsored by or representing the DPRK.

What does this mean for universities, their employees, and researchers?

Sanctions do not prohibit providing employment, education or training services to all persons from sanctioned countries. A person's origin from a sanctioned country does not automatically disqualify them from being approved as employees, students or research candidates. However, enrolling a person from a sanctioned country in a program related to 'export sanctioned goods', or enrolling a person from a sanctioned country who has links to a designated person or entity, increases the risk profile of the activity. The ASO does not consider a blanket restriction on enrolling all such persons to be the only way to mitigate risk.

Whether an activity constitutes a sanctions contravention depends on the specific circumstances. Sanctions frameworks differ. It is therefore important to reference the relevant sanctions laws for the specific sanctioned country when conducting an assessment.

Strict liability

Sanctions offences are strict liability offences for bodies corporate, meaning that it is not necessary to prove any fault element (intent, knowledge, recklessness or negligence). However, bodies corporate can prove that they undertook reasonable precautions and exercised due diligence to avoid contravening sanctions laws as a defence.

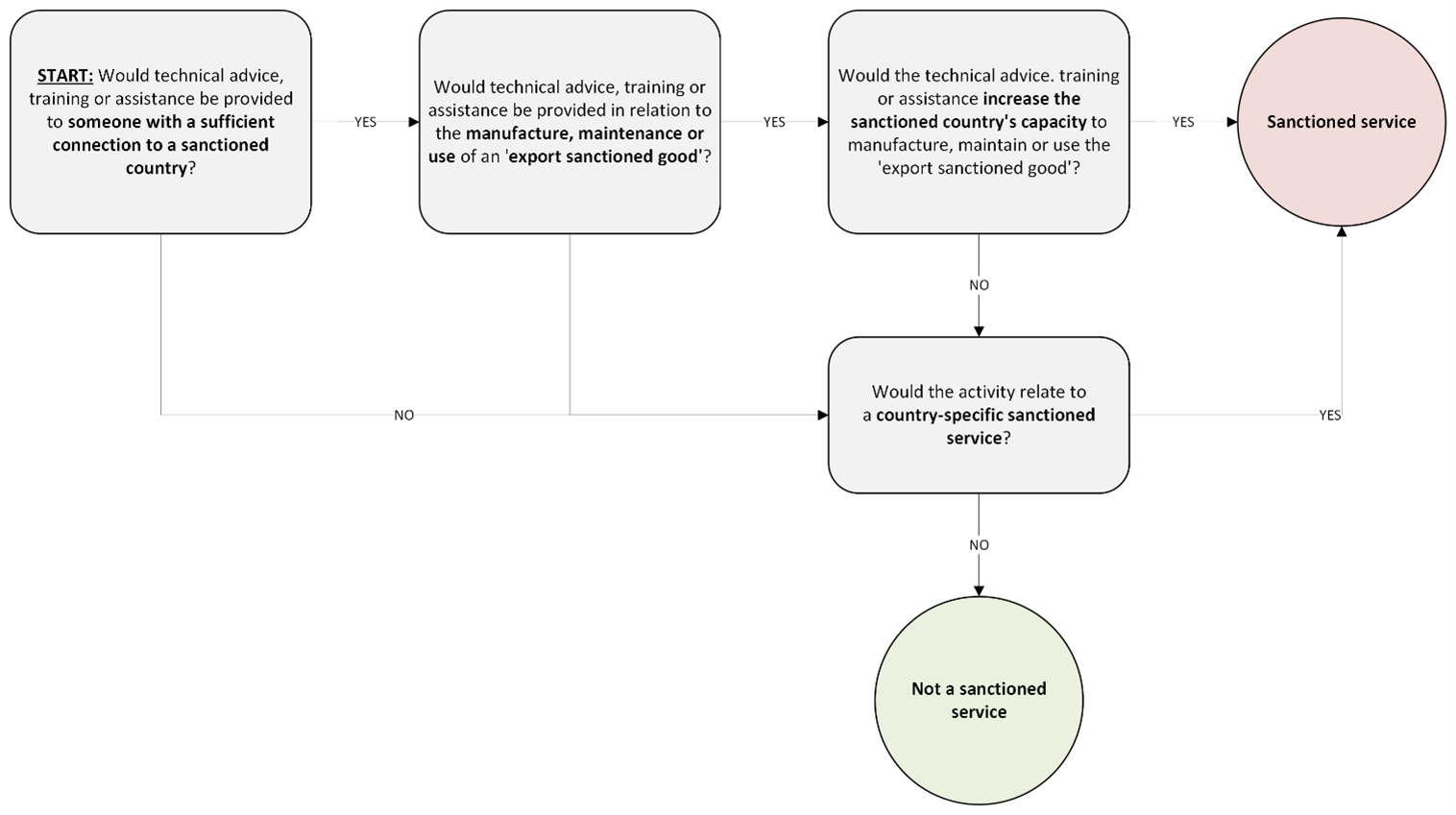

The following flowchart can help universities determine if a proposed activity would constitute a sanctioned service.

- Would technical advice, training or assistance be provided to someone with a sufficient connection to a sanctioned country?

- The following indicators can be used to gauge whether a person has a sufficient connection to a sanctioned country:

- the person's nationality or previous residence in countries subject to sanctions (e.g. Iran, North Korea, Syria etc.),

- the person's recent travel history to sanctioned countries or regions,

- the person's prior education or research conducted at institutions within sanctioned countries,

- the person's participation in research programs, conferences, or collaborations involving institutions or individuals from sanctioned countries,

- the person's involvement in research fields that are sensitive or dual use in nature, such as nuclear technology, advanced weaponry, or cybersecurity,

- financial support or scholarships the person has received from entities or governments in sanctioned countries,

- research funding or grants provided to the person by institutions or organisations with known ties to sanctioned countries,

- the person's past or present collaborations with researchers, institutions, or organisations that are based in or have ties to sanctions countries,

- the person's membership in academic or professional networks linked to designated persons or entities,

- the person's personal and professional connections, including family members or close associates who are citizens of or reside in sanctioned countries,

- the person's previous employment or internships with companies or organisations that have been designated,

- any unusual or unmonitored communications the person has had with persons or entities in sanctioned countries,

- a history of the person transferring or sharing of research data with entities in countries subject to sanctions,

- any attempts by the person to bypass or avoid compliance checks, such as providing incomplete or misleading information during the application process,

- the person's involvement in activities or public statements that show support for designated persons or entities, or sanctioned countries,

- any publicly available information indicating the person has connections with designated persons or entities, or sanctioned countries,

- any irregularities in the person's visa applications, travel documents, or travel patterns that suggest undisclosed ties to sanctioned countries.

- Would technical advice, training or assistance relate to the manufacture, maintenance or use of an 'export sanctioned good'?

This question involves two parts:

- Is an 'export sanctioned good' involved?

- Does the technical advice, training or assistance relate to the manufacture, maintenance or use of that good?

This question may be informed by:

- checking whether the good is an 'export sanctioned good' as defined under the relevant sanctions law for the sanctioned country (including any relevant Specifications/Determinations), which may be informed by whether it appears on the Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL); and

- checking whether the advice, training, or assistance would assist with or relate to the manufacture, maintenance or use of the goods.

- Would technical advice, training or assistance increase the sanctioned country's capacity to manufacture, maintain or use those 'export sanctioned goods'?

This question requires awareness of the aims of the research project, the impact of the technical advice, training or assistance, and what knowledge already exists in the public domain.

- A research project focused on advancing specific technologies or applications may present a higher risk of misuse. For example, materials science research could be repurposed to improve missile construction or nuclear capabilities. Broader, fundamental research (e.g. basic chemistry or physics without specific industrial or military applications) may pose a lower risk but still requires careful evaluation.

- If the technical advice, training or assistance associated with the research project directly improves the capacity to manufacture, maintain or use an export sanctioned good, the risks are higher. For example, if training improves the precision or efficiency of manufacturing sensitive technologies, there is a higher risk that it could enhance the military capabilities of a sanctioned country.

- Publicly available information (e.g. open publications, patents) is less likely to increase a sanctioned country's capabilities as it is accessible to all. New or proprietary technical knowledge not yet in the public domain could pose significant risks if shared, as it might give a sanctioned country an advantage they previously lacked, especially if it relates to dual-use or military technologies.

- Would the activity relate to a country-specific sanctioned service?

Country-specific sanctioned services are defined for Iran, Myanmar, Russia, Syria, Zimbabwe, DPRK, and specified regions of Ukraine (Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Sevastopol, and regions specified by the Minister) in regulation 5 of the Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011.

Know the research topic and outcomes

When evaluating technical advice, training or assistance as it relates to research projects, it is particularly important to consider the proposed thesis and outcomes of a project and whether the knowledge could be transferred to another field. If there are doubts about whether the technical advice, training, or assistance might involve 'export sanctioned goods,' seek legal advice on sanctions compliance. In the current dynamic geopolitical environment, low-tech items are increasingly used in military weapons, so examine the equipment to be used and any equipment or processes to be developed during the project.

Research supervisors must be vigilant when considering the training or supervision of higher degree students. Universities must ensure they have not indirectly participated in training or supervising individuals who later use the knowledge gained for prohibited purposes. It is important that universities ensure the projects they supervise do not contribute to the design of equipment or technology that may assist in weapons design.

When assessing 'fundamental research' without specific practical applications, sanctions risk should focus on the individuals involved. While technical knowledge from such research could potentially be misused, identifying specific prohibited purposes is challenging. Therefore, the person's history and connections with sanctioned entities and countries may be more reliable indicators of sanctions risk.

In addition to compliance with Australian sanctions laws, you should consider compliance with Defence Exports Controls, which are separate to sanctions. Defence Export Controls relate to goods or technology listed on the DSGL. Even if a research project will not involve such goods or technology, universities are encouraged to engage with the ASO and Defence Export Controls (DEC) when assessing the suitability of a project and student for enrolment. This is particularly important if there are questions about the end use or outcome of the proposed project, or if the knowledge or training could assist in developing new weapons.

Case study 1

An Australian university is funding a project with a local materials science expert from a sanctioned country to develop high-efficiency solar panels. This initiative supports the university's goal to advance renewable energy and cut carbon emissions.

The university assesses potential risks, noting that the technology could be misused for military purposes if linked to the sanctioned country. Although the researcher maintains extended family connections there, they have no other ties to the country or its designated entities.

After confirming this, the university deems the risk minimal and moves forward with the project. To prevent misuse, it enforces strict data access controls and regular audits. The university's risk assessment concludes that by taking reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence, these risks can be effectively managed.

Case study 2

An Australian university is considering a research collaboration with a biotechnology expert from a sanctioned country to advance medical technology. The project aims to enhance healthcare techniques and aligns with the university's mission to advance medical research.

The university's risk assessment reveals concerns that the biotechnology could be misused for weapons of mass destruction (WMD), such as biological agents or pathogens. The researcher's strong connections with the sanctioned country's government increases the risk of the technology being diverted for WMD development.

Further investigation confirms that these ties present a serious risk. Given the high potential for misuse and the inability to manage these risks by taking reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence, the university decides to withdraw from the collaboration.

Dealing with a designated person or entity

Australia has imposed prohibitions on dealing with certain persons, entities and assets as part of its UNSC and autonomous sanctions frameworks. These frameworks are respectively governed by the Charter of the United Nations Act 1945 and the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011.

Under Australian sanctions laws it is an offence to directly or indirectly make an asset available to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity. It is also an offence to use or deal with an asset, or allow or facilitate another person to use or deal with an asset, that is owned or controlled by a designated person or entity. That is, the assets must be 'frozen'. The prohibition on 'dealing' with assets includes using, selling or moving assets.

Universities must navigate sanctions risks related to prohibitions on providing assets to, or benefiting, designated persons or entities. When employing or enrolling any person, it is important to ensure that no asset will be made available to, or benefit, a designated person or entity. This includes verifying whether the person is themselves a designated person or has close connections to a designated person or entity.

DFAT maintains a Consolidated List of all designated persons or entities.

What is an asset?

For the purposes of Australian sanctions laws, an 'asset' includes an asset or property of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable. It can also include a legal document or instrument evidencing title to, or an interest in an asset – e.g., bank credits, travellers cheques, money orders, shares and securities.

Case study 3

An Australian university is considering a collaboration with a firm specialising in advanced agricultural technologies to enhance crop yields and sustainability. The project supports the university's goals in agricultural science and environmental sustainability, and the firm is selected for its innovation and expertise.

However, the university's risk assessment reveals that the firm is indirectly owned by a designated company through an investment chain. While the designated company is not directly involved in the research, it stands to benefit financially from the firm's success, which poses a significant risk of indirectly making an asset available to a sanctioned entity.

Further investigation confirms that the designated company is likely to gain from dividends or equity increases due to the firm's commercial success. Given this risk, the university decides to withdraw from the collaboration, as the potential for indirect benefit to a designated entity cannot be managed by taking reasonable precautions and exercising due diligence.

Case study 4

An Australian university is considering a partnership with a foreign tech firm to develop software for data analytics. The firm has a diverse ownership structure, and there are no direct links to sanctioned entities. The project aligns with the university's mission to advance technology and data science.

During its risk assessment, the university identifies that the foreign tech firm has several indirect connections to entities in sanctioned countries through its supply chain and financial backers. However, these connections are broad and not directly linked to the specific project.

In this case, the university assesses that there is no clear or specific evidence indicating a reasonable likelihood that the research partnership will lead to a contravention.

Sanctions permits

A sanctions permit is an authorisation from the Minister for Foreign Affairs (or the Minister's delegate) to undertake an activity that would otherwise be prohibited by an Australian sanctions law.

The Minister may grant permits in relation to both UNSC and autonomous sanctions frameworks. For some countries, both UNSC and autonomous sanctions apply. More detailed information on Australia's sanctions frameworks, including the specific criteria for granting permits under each framework, can be found on the DFAT website.

The criteria for sanctions permits under UNSC sanctions frameworks vary, as do the range of activities that the Minister can authorise. These activities tend to be more limited than those which can be authorised under autonomous sanctions frameworks. Additionally, some of the UNSC sanctions frameworks require the Minister to notify or receive the approval of the UNSC before granting a sanctions permit.

The ASO advocates for proactive risk management rather than relying on permits. Sanctions permits are generally appropriate only when there is a clear likelihood of a sanctions contravention occurring. For broad or non-specific sanctions risks, it's better to manage compliance through reasonable precautions and due diligence to prevent issues before they arise. To enable due consideration of any permit application, ASO must be provided sufficient detail of a specific contravention to which the application relates.

Further information on sanctions permits and how to apply for a sanctions permit.

What is the 'national interest' test?

All permits issued under autonomous sanctions frameworks must meet the same criteria, in particular that the Minister must not grant the permit unless the Minister is satisfied that granting the permit is in the 'national interest'.

This generally requires the Minister to be satisfied that the grant of a permit is beneficial, or advantageous, to the national interest. It requires a consideration of whether something is advantageous to the nation as a whole, as opposed to only a particular company, group or section within the nation, or to a particular region or locality.

If you consider an activity will result in a breach of Australian sanctions laws, you can apply for a sanctions permit via Pax. Please ensure you provide all necessary details of the proposed activity, and the other parties to it.

Further information on applying for a sanctions permit.

Case study 5

An Australian university is seeking to collaborate with a designated research organisation in a sanctioned country to develop advanced treatments for women's and children's health. This organisation possesses critical expertise and research necessary for the project.

The collaboration would involve providing significant funding to the sanctioned organisation in exchange for access to their exclusive research. This arrangement will certainly contravene sanctions related to providing funds to a designated entity.

However, the research promises substantial benefits. It could lead to breakthroughs in maternal and paediatric care, offering significant improvements in health outcomes.

The university acknowledges that proceeding with the collaboration will certainly contravene sanctions but argues that it is in Australia's national interest. Therefore, it applies to the ASO for a sanctions permit. The application emphasises the significant health benefits and the exclusive access to critical research not available elsewhere. It also outlines the university's risk management strategy, which includes stringent oversight of the funds to ensure they are used solely for the intended research and contractual safeguards to monitor and control fund usage.

Penalties for sanctions offences

Sanctions offences are punishable by:

- For an individual - up to 10 years in prison and/or a fine of 2500 penalty units ($825,000 as of 7 November 2024) or three times the value of the transaction(s) (whichever is the greater).

- For a body corporate – a fine of up to 10,000 penalty units ($3.3 million as of 7 November 2024 or three times the value of the transaction(s) (whichever is the greater).

Further information and resources

While this guidance note provides a framework for understanding key sanctions risks and compliance requirements, it is essential to remember that it does not cover every possible scenario. Sanctions compliance is an ongoing obligation rather than a one-time assessment. Sanctions measures and associated risks are constantly evolving, requiring regulated entities to continuously monitor and reassess their compliance strategies. Regulated entities are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their specific situations and ensure thorough due diligence in all activities.

Further information is available on the Department's website and in ASO guidance notes on specific sanctions topics. If you have any questions, you can make an enquiry through PAX portal or email at sanctions@dfat.gov.au.

Text contents of flow chart

Assessing whether an activity would constitute a ‘sanctioned service’ starts by asking whether the technical advice, training or assistance, is to be provided to someone with a sufficient connection to a sanctioned country.

If yes, is it being provided in relation to the manufacture, maintenance or use of an ‘export sanctioned good?

If yes, would it increase the sanctioned country’s capacity to manufacture, maintain or use the ‘export sanctioned good’?

If yes, the activity likely constitutes a ‘sanctioned service.’