Summary

- Australia needs to approach India both as a national economy and as a series of sub-national economies, each with distinct growth trajectories and regulatory regimes. Given that states control critical elements of the business environment, the settings of state governments will continue to impact Australian businesses in India deeply.

- As more economic decision-making responsibility is devolved to the states, they are being encouraged by the Central Government to take on the onus of reform, including for contentious issues such as land acquisition and labour. States are also being exposed to increasing competition, as the dynamic of both cooperative and competitive federalism gains traction. This dynamic will be an integral part of India's economic future.

- It will be important for Australian Commonwealth and state governments to project a joined-up approach given the challenges of getting noticed in a crowded market and that most Indian interlocutors will make little distinction between Australian states.

- This chapter examines how the sectors identified in this report intersect with particular Indian states. It seeks to provide a figurative heat map of opportunities, based on states' economic profile, growth trajectory and reform prospects.

Figure 27: Economic opportunities of India's Key Sectors and states

The inner circle identifies the 10 priority sates where Australia should focus. The yellow icons symbolise the 10 key sectors where Australia has competitive advantages.

The context of India's states

India's federated political system means it operates as a series of distinct sub-national economies each with its own growth drivers and investment climates and each requiring its own strategy. India's 29 states and seven union territories vary widely in terms of their population, economic growth, rate of urbanisation, natural resources, climate, access to ports, regulatory environment and the quality of leadership.

While Australia needs to continue to engage with India as a national economy including on its macro settings, India's federal structure means that states hold many of the levers controlling the investment climate. The progress of their reform agendas will combine to have a greater effect on India's economic future than that of the Central Government.

A number of states dominate India's economic output and international economic engagement, based on figures from the Indian Government's Economic Survey of 2016–17 and 2017–18:

- Eight states account for more than 60 per cent of the nation's economic activity

- Andhra Pradesh, the capital New Delhi and surrounding region, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

- Five states account for 70 per cent of India's exports

- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Telangana – in that order.

- Five states attracted 71 per cent of all FDI inflows into India from April 2000 to December 2017

- Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and New Delhi.

- Five states account for half of all tax collected by the GST

- Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat.

- India's consuming class across the eight prosperous states above have a higher share of household spending on travel, recreation, consumer goods, health and education.

Drawing from his experience as Chief Minister of Gujarat for over a decade (during which time he built a business-friendly, outward-looking economic base for the state), Prime Minister Modi has pressed for an Indian federalism that is both cooperative and competitive; cooperative, in terms of better state-federal relations revolving around more fiscal devolution to the states and building consensus on the reform agenda; and competitive, in terms of heightened incentives for states to compete for capital and press ahead with reform. Prime Minister Modi sees this as a core element of India's economic re-invigoration.

A competitive dynamic is not only driving progress among states, but also at the level of cities, known as 'competitive sub-federalism'. Competition is a critical element of Prime Minister Modi's signature Smart Cities initiative, which involves cities bidding for funding grants for urban projects.

The dynamics of competitive federalism and competitive sub-federalism are being embedded into India's economic future and these dynamics will remain a key feature of the Indian economy out to 2035. Australian Government and business should therefore take a sub-national approach to engagement with India to target resources in India's most competitive and complementary regions.

The nature of commercial markets in India, as elsewhere, is that they do not strictly coincide with state boundaries. Depending on the particular sectoral opportunity, the customer base involved and the presence of any local partners, the most appropriate market may cross state boundaries. The National Capital Region of Delhi, comprising not only the seat of Central Government in New Delhi, but also segments of three neighbouring northern Indian states, and several of their key satellite cities, is a prime example of a key market that will strongly engage Australian interests in north India.

Alternatively, the most serviceable market for a particular opportunity might consist of a metropolitan city at the nucleus surrounded by its urban and rural hinterland. For example, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region consists of India's financial capital and surrounding satellite towns. A hub and spoke model will often be useful to reach into the market in question.

Regardless of whether the most appropriate market for Australian commercial engagement crosses state boundaries, state governments set many of the conditions which determine the business environment. Accordingly, the intersection of states and sectors lies at the heart of this Strategy. It recommends a strategic investment by government in 10 priority states.

Why focus on states?

India's political structure

India's federal division of powers means the states are integral to its economic future. Constitutionally, the Central Government's responsibility includes inter-state relations, national security, foreign affairs, trade and commerce, national highways, ports and railways. The Central Government controls rule-setting over market access, trade, investment, as well as some of India's most heavily regulated sectors (including defence and financial services).

State governments, on the other hand, have competence over law and order, police, health, education, water and electricity. In effect, states oversee key inputs to business including physical infrastructure (roads, electricity, water, and sanitation), a majority of business licences, as well as social infrastructure, such as schools and healthcare facilities.

Competence is shared over concurrent subjects including land acquisition and labour, with the Central Government having precedence in the event of a conflict.

Greater decentralisation

India's states are assuming more economic decision-making power from the Central Government. The historic distribution of economic decision-making power between the Centre and the states overwhelmingly favoured the Central Government. But liberalisation of the economy in the 1990s saw the start of a shift away from centralised economic policy-making.

The Central Government retains a greater role relative to the states in influencing public spending priorities. While the Centre has superior financial powers and a greater share of the power to tax, including import or export duties and corporate taxes, the states have a larger share of responsibility for the delivery of public services such as policing, education, health and utilities.

Increased fiscal devolution is providing states with more autonomy on public spending decisions. The share of untied tax resources transferred by the Central Government to the states was radically increased in 2015, from 32 to 42 per cent (as recommended by the Finance Commission in a constitutionally-mandated process occurring every five years). The Central Government has also cut down on tied social policy funding to states (known as Centrally Sponsored Schemes), which had seen the Centre re-appropriate some of the responsibility over social policy. States therefore have more flexibility in catering to the significant diversity in local requirements and their own priorities.

The collective fiscal size of states is also increasing. Over the last few years, states have been collectively spending more than the Central Government, at a rapidly increasing rate. In 2016–17, combined state expenditure was approximately 70 per cent more than Central expenditure (Central expenditure here excludes grants to the states). This was only 6 per cent more in 2011–12.

The GST is contributing to the reconfiguration of Centre-State fiscal relations. The GST Council, which has representation from all states and the Centre, gives states a major role in the way the GST is administered. At the same time, the states now have a diminished ability to use tax policy as a vehicle to attract investment. They will need to find more innovative ways to shape the investment climate to lure investors.

Economic divergence

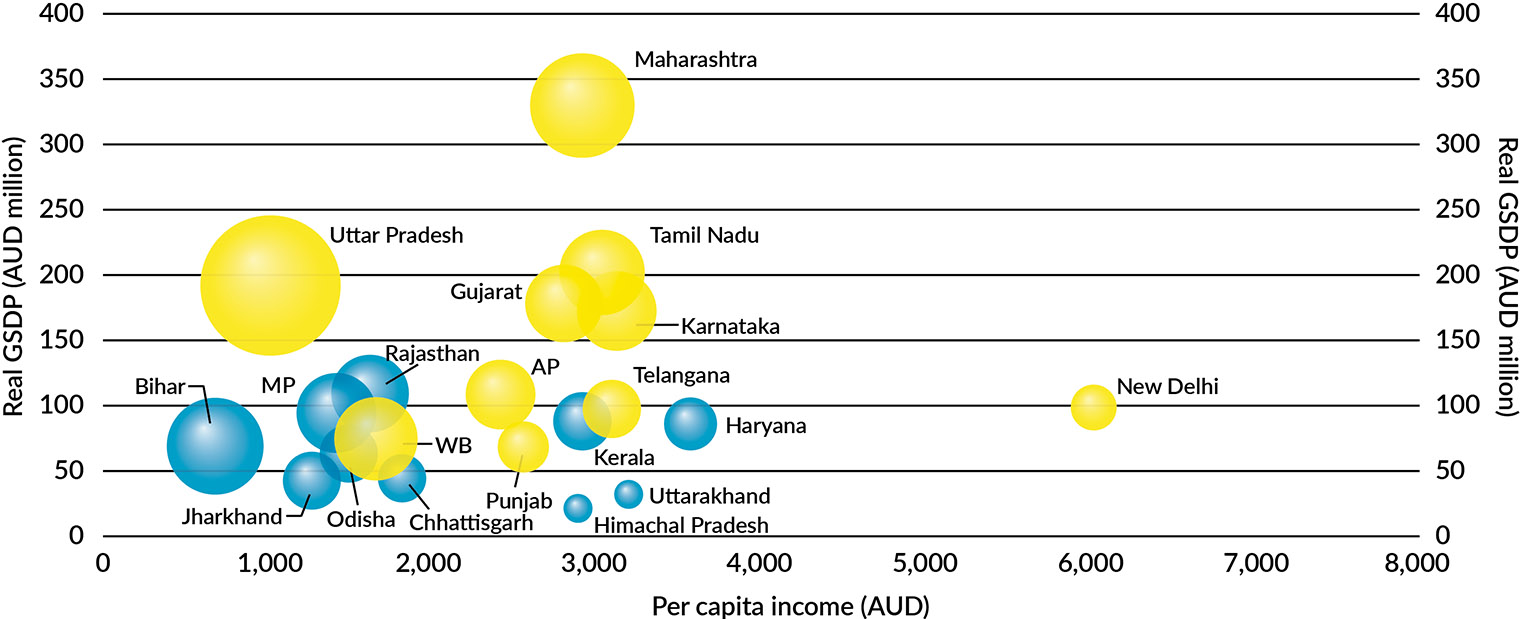

There are wide variations in the wealth, demography, investment climate and the priorities of states, demanding a granular approach for Australia. Figure 28 demonstrates the variation in per capita income, gross state domestic product and state population of 20 major Indian states.

Figure 28: Gross State Domestic Product and Per Capita Income (2016–17)

Source: Ministry of Finance (IN). Economic Survey 2017–18. New Delhi IN: Government of India; 2018.

Note: Per capita income as measured by per capita net state domestic product at current prices (2011–12 series), real GSDP at constant prices (2011–12 series). Delhi refers to the National Capital Territory (and not the National Capital Region). Bubble size represents state population.

India's current level of regional economic divergence is unparalleled. By 2014, the average person in the three richest states (Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra) was three times as rich as the average person in the three poorest states (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh). As outlined in the 2016–17 Indian Economic Survey, 'India stands out as an exception... Poorer countries are catching up with richer countries, the poorer Chinese provinces are catching up with the richer ones, but in India, the less developed states are not catching up; instead they are, on average, falling behind the richer states'.

The divergence across the states demands a focused approach—what works federally, or in one state, does not necessarily work in another. Take demography as an example. Although it is often said that India is young, the mean age in the more prosperous southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu is 30 years old, while in the northern hinterland states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh it is only 19, approaching a generation apart. Whereas fertility rates in Kerala and Tamil Nadu are lower than the replacement rate, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar still record high fertility ratesxxx of 3.1 and 3.3 respectively (based on 2016 figures).118 And while life expectancy in Kerala and Tamil Nadu is similar to that in middle-income countries, in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar it compares to low-income countries.

Political alignments or differences between the Centre and state governments have undoubtedly played a part in the variation of state responses to the national reform agenda. Some states ruled by BJP governments have demonstrated better reformist credentials under the ruling BJP at the Centre.

Competition and cooperation between states

Competitive and cooperative federalism has become a powerful dynamic of change, which is seeing states compete to improve their business environments [see Chapter 15: Understanding the Business Environment]. For example, a number of states have taken difficult steps on land acquisition and labour reform after the federal politics of reform stifled national legislation on these matters.

There are recent examples of cooperation on national reforms. As of April 2018, 27 of India's 29 states have joined the power sector bailout program, the Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana (UDAY), to revive insolvent power distribution companies as a result of uneconomic pricing in the electricity sector. The passage of the historic GST, despite its less than optimal structure and implementation challenges, is a game-changing reform achieved through consensus between the federal government, all 29 states and seven union territories.

How this will likely evolve out to 2035

Key judgement

Cooperative and competitive federalism is being hard-wired into India's economic future and this will continue out to 2035, amplifying the importance of states.

India's political structure

The link between tangible development and electoral success will strengthen out to 2035. Considerations of caste and community will remain important electoral drivers, but will continue to decline relative to the currency of tangible economic development, including job creation. This will fuel competition between states. So long as market forces are in play, states will continue to compete to bolster their electoral prospects.

Continuing decentralisation

India's federal balance is likely to continue to move towards delegating decision-making power to the states. Despite the state-level consolidation of the BJP, regional parties will continue to be a salient feature of Indian politics, reiterating demands for regional autonomy.

Widening inequality between states will also feed demands for increased regional autonomy. Although richer states including Haryana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka raise around 70 per cent of revenue from their own taxes, contributing more to the Centre's finances per capita, they receive fewer funds from the Centre. By contrast, poorer states, such as Assam, Jammu and Kashmir and Bihar raise only around 20 per cent from their own taxes, making them more dependent on transfers from the Centre.

As economic inequality continues to widen, and as richer states continue to age, the political acceptance of this redistribution will likely be strained, adding to pressures on social cohesion and demands for regional autonomy.

Institutional longevity

The dynamic of cooperative and competitive federalism has been institutionally enshrined in the form of NITI Aayog, which replaced the former Planning Commission. NITI Aayog is directly engaging chief ministers, nudging states to reform with new policy tools, building capacity, encouraging policies in the collective interest and highlighting best practice.

Enabling environment

The enabling tools encouraging competition between states are expanding. The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion's (DIPP) 98-point Assessment of State Implementation of Business Reforms ranking states' relative competitiveness is driving the incentives for states to reform. Cementing and sustaining these incentives is a key priority for the DIPP, including through greater awareness raising of the rankings, transitioning from self-assessment to assessments by business to build greater public confidence in them and privileging newly reformed processes that are enshrined in legislation or completed online, rather than manually.

The number of indices ranking the performance of states, including on health, gender, education, governance and other indicators, is continuing to grow. Similarly, indices comparing cities and districts are also emerging. In March 2018, NITI Aayog released a ranking of 115 districts as part of the Transformation of Aspirational Districts program.

Decentralised foreign engagement

A greater share of India's foreign engagement will shift from national capitals to state capitals out to 2035.

Prime Minister Modi has encouraged this decentralisation since he took office. In 2015, the India-China Forum of State/Provincial Leaders was formed, the first bilateral forum of its kind for India. In 2017, Prime Minister Modi attended the first collective meeting of 16 Russian regional governors. In April that year, financially sound state governments were empowered to borrow directly from ODA partners. More broadly, there has been an increasing emphasis on sister city and sister state agreements in India's East Asian relationships, in particular. And there is great symbolism in Prime Minister Modi's hosting of foreign leaders in Indian states.

In parallel, Australian state governments will also continue to expand the breadth and resourcing of their foreign engagement and economic diplomacy out to 2035.

Opportunities for partnership

The need for business to develop state and city based strategies

India is far too large and too diverse to approach as a national market. Commercial success in India will increasingly require businesses to recognise the pivotal role of states and the importance of focusing on key markets at the sub-national level. This will demand that businesses dedicate resources to:

- looking for the appropriate beachhead market

- assessing the economic potential, market size, and operating environments of states and cities

- evaluating the risk-adjusted opportunities for the business

- developing targeted strategies for the most attractive market segments [see Chapter 15: Understanding the Business Environment].

When considering market entry, the kind of considerations business should examine also include:

- determining the best partners and customer bases

- adopting an appropriate legal and tax structure

- conducting legal, financial and technical due diligence on any potential partner or transaction to minimise risk.

Assessing sub-national markets will necessarily involve an analysis of leading indicators that measure the competitiveness of states. To this end, aggregated Indian statistics on the national economy as a whole are less useful in comparing markets. As a starting point to investigate markets, a snapshot of each of India's 29 states is annexed, and given its significance, the National Capital Region of Delhi is also included.

These snapshots are designed to introduce major features of each state economy and some of the most significant sectoral opportunities for Australia. They provide an evidence base for the competitiveness of states and offer a starting point to assess the risks and opportunities in each state, including quantitative and qualitative indicators of:

- market size (population, gross state domestic product, area)

- growth drivers (growth rates, urbanisation, the number of million plus cities)

- infrastructure (road density, rail density, power deficit)

- the regulatory environment (ease of doing business ranking, quality of governance ranking)

- human development (literacy rate, male-female literacy gap, ranking on gender performance)

- the state of public finances (fiscal deficit to GSDP ratios, health and education expenditure)

- openness (FDI inflows and major foreign engagement)

- industry clusters and sectoral composition of the economy

- track record on reform and future priorities

- political leadership and stability.

The snapshots are not designed to be exhaustive or to be solely relied on for commercial considerations – they are necessarily selective and general in their scope and capture the current picture as at April 2018. There is also an increasing array of products profiling state economies, including subscription-based services, to help business tailor their investment decisions.

The role of the Australian Government in driving a state or city focus for India

While the shape of resourcing will ultimately be defined by a range of objectives for the bilateral relationship, the Australian Government should align its resources across government to the priority states, including by:

- sharpening the focus on priority states in existing initiatives

- regional aid funding (Australia does not have a bilateral aid program with India but India is included in some regional aid programs)

- the Direct Aid Program (modest programs administered by the Australian High Commission in New Delhi, the Consulate-Generals in Mumbai and Chennai, currently valued at around $1.2 million)

- Special Visit Programs

- Public diplomacy programs

- Australia-India Council funding

- Australia India Leadership Dialogue participants

- establishing or strengthening the Australian Government network in relevant regions, including with respect to DFAT, Austrade and other government agencies

- supporting ministerial and senior official engagement with key cities and states

- establishing formal government to government mechanisms

- facilitating sister-city and sister-state partnerships, based on complementarity

- developing sector or state specific sub-national dialogues

- engaging closely the relevant state cadre of the Indian Administrative Services, such as the Chief Secretaries of States and other senior officials, including outreach to expose them to Australian capabilities

- increasing the outreach to alumni of Australian universities in key states and the diaspora communities of key states

- conducting awareness-raising public diplomacy events or nominating champions in key states.

The role of Australian State Governments

The Australian Government must foster a coordinated and coherent approach while supporting state and territory engagement in India. For many Indian interlocutors, there is little distinction between Australian states. To avoid diluting Australia's brand in what is already a crowded market, there is a case for more cohesion on the respective strategies of states and the Commonwealth, and joined-up approaches across sectors where several states are active (including education and training, agribusiness, tourism, resources and energy). State offices in India should also work closely with Austrade to ensure a national approach. What follows is a summary of current engagement by Australian states.

New South Wales

The New South Wales (NSW) Trade and Investment Action Plan 2017–18 identifies India as one of 10 priority international markets. The state's representative is based in Mumbai and the NSW Government has appointed a Special Envoy to India (currently former Premier Barry O'Farrell), who travels representing the Premier of NSW. NSW has sister-state relationships with Maharashtra (2012) and Gujarat (2015), encompassing collaboration on vocational skills training, agriculture, water management and waste treatment technology, and NSW capability in smart cities and infrastructure. Key outcomes in Maharashtra include a partnership to enhance collaboration in the start-up and technology sectors, a government to government contract for water resource management projects, a TAFE NSW contract with the Maharashtra State Board of Technical Education for teacher training and course development, and cultural exchanges between state galleries. There has been little progress in Gujarat to this point, with delays on both sides.

Victoria

In January 2018, the Victorian Government launched a 10-year India engagement strategy focusing on education, health and liveable cities. The strategy highlights the important personal and economic connections Victoria shares with India and identifies opportunities for Victoria and India in education, health and liveable cities and places, as well as other emerging sectors. Victoria is building relationships with India's southern states and Delhi NCR, including Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Telangana. Victoria has the largest footprint in India of all Australian states, with offices in Bengaluru and Mumbai that are led by the Victorian Government Commissioner to South Asia.

Queensland

The Queensland Government's Trade and Investment Strategy identifies India as a target market and India was one of seven markets featured in the trade and investment program of the 2018 Commonwealth Games. Trade and Investment Queensland has an office in Bengaluru. Queensland's sectoral interests in India are agribusiness, resources and energy (including METS), education and training and tourism.

Western Australia

Western Australia was the first Australian state to open a trade and investment office in India in 1996. It maintains representation in Mumbai. In December 2016, Western Australia established a sister-state relationship with Andhra Pradesh, with a focus on collaboration and business to business support in its key sectoral focus areas of mining and mining services, education, dryland agriculture, energy production and distribution, water, road safety and medical technology.

South Australia

South Australia launched a 10-year India Engagement Strategy in October 2012. South Australia has used annual business missions to improve India literacy, develop exposure, and facilitate collaborative opportunities for South Australian businesses. The state's engagement activities are supported by a representative who is embedded in Austrade, Mumbai. An updated Strategy released in March 2016, sharpens the focus of the strategy by promoting sub-national engagement. South Australia established a sister-state relationship with Rajasthan, given Rajasthan's priority needs and its complementarity with South Australia's expertise, specifically in water and environment management. The Rajasthan Centre of Excellence in Water Resources Management is a major outcome from this relationship and work is underway to establish it. Various projects are in the pipeline to assist in building capacities, showcase South Australian water technologies, and to create commercial opportunities. South Australia will continue to focus on water and environment, premium food, beverage and agribusiness, and education as priority sectors for ongoing engagement with India.

Tasmania, Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory

Engagement by Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory in India is currently limited, although there is growing consensus about India's importance among business and government, and high-level visits have taken place.

Success to date

Australian states operating in India have variously found that:

- Successes have been slow to eventuate and one of the key sources of frustration for states is a perception their efforts are not reciprocated.

- Given global competition, relationships have been overwhelmingly driven from the Australian side.

- Regularly visiting India is important to build relationships especially in the early stages of the relationship.

- Indian states often expect relationships to begin with inward investment from Australia in small projects.

- Indian states often expect to advance discussion in the context of government-hosted trade events so managing their expectations about the representation that can be offered is important.

- Changes in political and bureaucratic leadership on both sides can affect progress.

- Having a representative on the ground can help to advocate for the relationship, expedite processes, bridge cultural differences and help with coordination/communication.

- Signing government-to-government MoUs can be a credible pathway to engagement with commercial operators or chambers of commerce in Indian states, acting as a seal of endorsement from the relevant Indian state government, but establishing a project plan to give practical effect to MoUs is crucial.

- Executing projects and receiving payment from Indian states can take a long time due to the number of approvals required, often right up to the Chief Minister's Office.

- There are advantages to targeting dynamic and influential leaders in Indian states or developing high-level champions for the relationship on both sides.

- Australian Government support for state and territory engagement can often be required to show endorsement, secure access and lend credibility.

- The appointment by Australian states of a special envoy to India can help drive state strategies and build personal relationships.

Constraints and challenges

Some of the risks to a strategy based on states and cities include tight fiscal conditions and capacity constraints within the states. The capacity of Indian Governments at all levels is low – this is more pronounced at the state level.

The small size of well-trained personnel and administrative resources undermine state capacity, and state governments display particular weaknesses in annual and mid-range planning, coordination, financial and budget processes. Besides weaknesses stemming from the structure of state bureaucracies, political processes contribute to capacity concerns. For example, many state legislative assemblies sit for only 30 to 40 days a year, without adequate time for legislators to scrutinise bills and without the rigour of permanent standing committees.

Compared to international standards, Indian states rely much more on devolved resources and much less on their own tax resources. The RBI has expressed concerns about the deterioration in the state finances in recent years – the Gross Fiscal Deficit to GSDP ratio of states averaged 2.5 per cent in the five years to 2015–16, as compared to 2.1 per cent in the five years previous. But the RBI has described the current fiscal policies of states as broadly sustainable in the long run.

This all points to weak capacity among states to manage resources efficiently, relatively tight fiscal environments, at least in the short term, and limited ability to back up aspirations to foreign economic engagement with the bandwidth to engage, access to capital or an ability to pay.

The prospects of Indian states and cities can be closely linked to political leadership rather than enduring institutions. Political churn can result in rapid change in the competitiveness of states. And intense political competition is part of the DNA of the Indian system (state governments are elected for five year terms).

Governance of cities, in particular, remains weak. The political empowerment of cities is impeded by the limited tenures of mayors and the fact that a significant share of executive power is vested in Municipal Commissioners who are appointed by state governments. The overlapping responsibilities of urban bodies can mean it is unclear which body to target as a partner for engagement.

Urban interests are systemically under-served. Urban and rural electoral constituencies are still distributed on the basis of the 2001 census, with electoral boundaries and the number of seats frozen by law until 2026 – in effect, until after the 2031 census. While the 2001 census reflected an urbanisation rate of 28 per cent, the 2011 census reflected an urbanisation rate of 31 per cent and this is forecast to increase to over 40 per cent by 2035. The upshot is that until 2035, towns and cities will continue to be under-represented politically; so rural interests will continue to distort policy priorities of the state and federal government.

Low 'India literacy' among Australian state and federal governments will also pose a challenge. By necessity, a granular approach demands deeper understanding, but in a number of the states identified as priority states, there is no current presence of any Australian Government agency or any significant Australian business presence. While English is widely spoken across government and business regional languages become more important when directly engaging states and cities.

Where to focus

Of India's 29 states, 10 emerge as priorities for Australia. The selection of 10 priority states takes into account their current and future economic potential, growth trajectory, regulatory environment, ease of doing business, openness, human development and reform prospects. It also takes into account the risks and opportunities in each state for Australia, given our competitive strengths.

These 10 priority states represent those where the returns from strategic investment by government will be the greatest. But this does not suggest that the most logical commercial marketplace for a business will coincide with state boundaries – although state governments remain primary actors in determining the business environment.

This also does not imply that existing or future engagement should cease in other states, or that they do not offer opportunities. For example, South Australia's focus on Rajasthan makes sense given the spread of South Australia's interests.

The dynamic of competitive federalism means that the relative competitiveness of states will not remain static. The selection of these 10 priority states is based on the current evidence. Consideration must be given to the level of market saturation or crowding by other players.

Ten Priority States

First, there are the states with the greatest economic heft – Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu – and among the fastest growing – Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The four economic powerhouses of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are large contributors to GDP, focused on the 'investment climate' with relatively high rates of urbanisation and increasingly sophisticated consuming classes. Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have strong economic momentum driven by a focus on the ease of doing business, infrastructure development, and abundant natural resources. There is strong competition from foreign players in these six states.

Second, there are the states with compelling sectoral opportunities – West Bengal for resources and METS and Punjab for agribusiness and water.

Besides states with immediate and medium term opportunities, there is also value in early investments in states with long term commercial prospects; foremost among these is India's most populous state – Uttar Pradesh. While other states present clearer commercial opportunities in the short to medium term, this is a decidedly long term play, with a higher risk/higher reward profile, for which a targeted, phased approach is appropriate. And given the state's political importance, there are also flow-on benefits for the broader bilateral relationship.

In a category of its own is the National Capital Region, which is not a state, but an inter-state region comprising the city of New Delhi and surrounding districts. It is important both as one of India's most dynamic economic hubs, but also as the seat of the Central Government.

The priority states are profiled below.

Maharashtra

India's most economically advanced and second most populous state, Maharashtra offers diverse opportunities encompassing education, training and skill development, urban infrastructure, financial services, agribusiness, transport and energy sectors. The state capital Mumbai, the wealthiest city in South Asia, serves as India's financial and film capital, akin to combining New York and Los Angeles in one city. Mumbai is the fulcrum of India's prosperous western region, housing the headquarters of India's national financial institutions, regulators, major banks and leading corporates as well as the gateway for imports into western India. Maharashtra's second (Pune) and third (Nagpur) largest cities are industrial powerhouses in their own right. Maharashtra's GSDP has grown at 7.3 per cent per annum over the five years to 2017 and the state accounted for 31 per cent of FDI inflows from 2000–2017.

Gujarat

As India's fifth largest state economy, Gujarat holds promise for Australian capabilities in education, training and skill development, renewable energy (solar, wind and water technologies), transport and urban infrastructure. The state is an industrial centre closely integrated with seaborne export markets. Its per capita income is 40 per cent higher than the national average and as home to Prime Minister Modi, receives significant national attention. Its strong economic performance has been driven primarily by infrastructure development, public service accountability, fiscal consolidation and streamlining regulations for business. Much of Gujarat's heavy industry is better suited to the large foreign players already engaged in the market, but opportunities for Australian business lie in supplying services as adjuncts to these larger projects.

Karnataka

Karnataka is a significant technology-enabled growth engine in India's south, complementing Australian strengths in innovation (nanotech, ICT, healthcare, start-ups, and niche agribusiness technology), best practice water management, life sciences and urban infrastructure. The state capital Bengaluru is the Silicon Valley of India, home to the fourth-largest technology cluster in the world. Bengaluru is the epicentre not only of India's IT, IT-enabled services, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology sectors, but also India's successful space program and India's start-up ecosystem. There are also opportunities for industrial investment in the state's second largest city Mysuru (in food processing and engineering) and the state's major port in Mangalore (in the resources sector).

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu is India's second largest economy and a highly urbanised, leading manufacturing state, offering opportunities in advanced manufacturing, urban infrastructure and water management. The state capital Chennai, the 'Detroit of India', is the centre of Indian automobile and component manufacturing and one of the world's top 10 automotive hubs. The state is a major agricultural producer and a major importer of Australian pulses and grains. Tamil Nadu's wind energy potential is world class. The state has among the highest per capita incomes and best health indicators in India.

Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh leads on the ease of doing business rankings and the state's GSDP has been growing at 11 per cent per annum over three years to 2017. The construction of a greenfield capital city has attracted major foreign players and offers opportunities for Australian infrastructure and urban development providers. The state's resources and energy sector matches Australian capabilities in mining, METS and renewable energy technology. Following the state's bifurcation in 2014, when the state's former north-western region was carved out to become a separate state, Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu embarked on an ambitious plan to rebuild the state economy, attract investment, pilot policy reforms and drive innovation. Naidu spearheaded Hyderabad's development from 1994 to 2004 and is bringing a similar zeal to major state-building projects. The port city of Vishakhapatnam, with the state's highest per capita income, is being developed as a new fintech hub.

Telangana

Telangana, India's newest state and one of India's fastest growing economies (experiencing 9.5 per cent per annum growth over three years to 2017), holds potential for Australia across its biotech, health, energy, fintech, innovation and start-up eco-system. In 2016, only three years since its formation, Telangana ranked equal first (with Andhra Pradesh) on the ease of doing business. Telangana's capital and economic epicentre is the IT, pharmaceuticals and Telugu-language film hub of Hyderabad. The city is India's sixth largest metropolis and a home to major corporates including Facebook, Google, Apple and Microsoft.

West Bengal

West Bengal, India's third most populous state, is positioned as a regional hub for Australian engagement on mining and METS, including as the gateway to the mineral-rich states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha. West Bengal is the centre of India's mining and resources sector. West Bengal has been the most significant METS market for Australian companies in India. West Bengal is also a significant healthcare hub for eastern India, a gateway to the northeast and a strong agricultural producer. The state capital of Kolkata is India's third largest metropolis, re-emerging as a growth centre and is home to Coal India. Kolkata is projected to be in the top 10 fastest growing cities in Asia out to 2021.

Punjab

Punjab offers opportunities in agribusiness, as an agricultural powerhouse producing 16 per cent of India's wheat, 11 per cent of rice, and a major share of diary. Over 80 per cent of the state is under intensive agriculture and agricultural yields per hectare are around double the national average. There are also sectoral opportunities in water management, given irrigation and groundwater quality challenges, as well as in sports. Punjab remains among the largest sources of Indian migrants and students in Australia, yielding strong diaspora connections. Although Punjab's economy is currently sluggish, exacerbated by governance challenges, it remains a relatively prosperous state and a breadbasket, accounting for 20 per cent of national food production. Pressures on productivity and sustainability have started to affect the agricultural sector, but this holds promise for Australian expertise in conservation agriculture and water management.

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh is India's largest state of over 220 million, a bellwether for national politics and India's third largest state economy driven largely by agriculture. It remains one of India's less developed states. The landlocked state has struggled with poor natural resource endowments and Australian commercial engagement has been limited to date due to poor perceptions of the ease of doing business and infrastructure gaps. But the state has unparalleled scale, untapped markets and out to 2035, the significance of its size and national political clout will only increase. Although per capita incomes are low across the state as a whole, there are pockets of economic potential with relatively higher income segments, particularly in the state's west. Development in western Uttar Pradesh is driven by its proximity to New Delhi, including in the cities of Ghaziabad, Meerut, Mathura as well as Noida, north India's emerging IT and business process outsourcing hub. Lucknow, the state capital, is the base of India's largest tanneries, a centre of wheat, rice and sugarcane production, and emerging centre for aeronautical engineering. And Agra is a major agricultural processing centre, including of cotton, dairy and flour milling.

For Australia there are long term commercial opportunities in transport infrastructure, agribusiness and dairy, and skill development. While these opportunities will not be conducive to commercial engagement in the short term, they warrant early government investment to position Australia well into the long term. This Strategy recommends a targeted, phased approach.

Phase 1: As the state rolls out a large number of brownfield road projects, Australia should invest in a transport infrastructure partnership to assist in assessing the feasibility of road projects in the pipeline, including their financial viability. In agribusiness, the state will have long term demand for capital investment in food processing, accounting for about a fifth of India's total food production, including a major share of pulses, dairy, wheat, sugarcane, maize, potatoes and mangoes. Australia should ramp up engagement on specialised agricultural services using ACIAR expertise.

Phase 2: As discussed in Chapter 3: Education Sector, the skills challenge facing India cannot be entirely met through bricks and mortar. We need to develop digital delivery with workable revenue models. These should be developed and trialled elsewhere. Once proven, their deployment in Uttar Pradesh could be transformative.

Delhi – National Capital Region

Delhi NCR comprises not only the seat of Central Government in New Delhi, but also segments of three neighbouring north Indian states: Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. It is a major economic hub, comprising multiple special economic zones and industrial clusters, such as the IT services centres of Gurugram and Noida and the manufacturing hubs in Faridabad and Alwar. NCR has a prosperous consumer base – the per capita income of New Delhi is almost three times the national average. It accounts for a fifth of FDI inflows into India. Australia's sectoral interests in NCR span financial and other services (particularly in Delhi proper and the Haryana sub-region), infrastructure, tourism, science and innovation, health and agribusiness (in the Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh sub-regions). A large number of Australian companies see NCR as an entry point and base for doing business in India. Governance of the NCR is split between the Central Government, three states and one union territory government, as well as an array of municipal bodies. So the relevant government counterpart depends on the particular sectoral opportunity and sub-region involved.

Recommendations

- 73.Ten priority states

Focus on 10 priority Indian states for strategic investment by government, namely Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, West Bengal, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi NCR

- over time, Austrade should realign its priorities and presence in line with the states, cities and sectors identified in this report.

- 74.Increase the Australian Government's footprint in India

- 74.1Upgrade the small Austrade presence in Kolkata into a full Consulate-General

- focusing on economic diplomacy in mining and resources in India's eastern mineral-rich states of West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha

- a mission in Kolkata would represent a strategic investment in Australia's ability to access opportunities in India's resource-rich eastern states and the emerging north-eastern states

- this could build closer relationships with state governments, including on shared policy experiences and advocacy for reforms in the Indian mining sector and to service the expanding METS sector in Kolkata, other mining-related activity and attract inward investment.

- 74.2When resources permit, establish a Consulate-General in Bengaluru to focus on economic diplomacy in technology and innovation

- a post in Bengaluru would represent a strategic investment in Australia's ability to access opportunities in the world's fourth largest, and second fastest growing, technology cluster.

- 74.1Upgrade the small Austrade presence in Kolkata into a full Consulate-General

- xxx Total fertility rate (TFR) in simple terms refers to total number of children born or likely to be born to a woman in her lifetime if she were subject to the prevailing rate of age-specific fertility in the population. TFR of about 2.1 children per woman is called Replacement-level fertility.