Summary

- The Australian Indian diaspora is a national economic asset, and should be engaged and deployed as such. The Indian Government puts a large effort into working with this diaspora. The Australian Government must also do so.

- Harnessing the entrepreneurial spirit of this rapidly growing community, particularly its willingness to innovate and take risks, and its knowledge of the Indian market, will enhance the future productivity and resilience of the Australian business sector.

- At almost 700,000 strong, Australia's Indian diaspora, comprising both Australians of Indian origin and Indians resident in Australia, makes a significant contribution to Australia's society and economy

- they are the second highest taxpaying diaspora, behind the British

- Indian-born Australians are expected to outnumber Chinese-born Australians by 2031, reaching 1.4 million.128

- Migration from India to Australia increased dramatically between 2006 and 2016, more than doubling the numbers of the India-born population92

- this surge in education-related and skilled migration coincided with a period of significant labour shortages across the economy during Australia's mining boom.

- As we leave the mining boom behind, we can do better in targeting and supporting the highly qualified professionals and high calibre students who will help drive future economic growth in Australia and integration with India.

- There are good examples, globally, on how to engage the diaspora more effectively. Similar surges in the Indian diaspora in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Singapore commenced earlier than Australia's and were focused around the rapid expansion of the IT industry.

- Compared to the professional Indian diaspora in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Singapore, the Indian diaspora in Australia are yet to achieve a similar level of influence in higher levels of state and federal politics, academia and business.129

- As our Indian diaspora become more politically active, both within the electorate and in the political class, the impetus of Australian state and federal governments to promote the bilateral relationship will only increase.

- Embracing the contributions of our Indian diaspora, and giving them prominence in bilateral relations; strengthening diaspora organisations; attracting talent in sectors that will drive Australia's growth; and ensuring this talent is mentored and supported can result in an Australian Indian diaspora who:

- validates Australia as an innovative, diverse, safe and prosperous society and improves Australia's standing and influence in India

- crystallises the potential of the Indian economy as a driver of Australian growth

- helps to interpret India for the broader Australian community.

Leveraging the Indian diaspora

In my consultations with state governments, I was struck by how the Indian diaspora is already clearly on their political radar. This will only grow as the diaspora itself becomes more politically active. In this, Australia over the next 20 years may well move along a Canadian path where Indo-Canadians are prominent in all political parties and hold high ministerial positions. A politically active Indian diaspora will inevitably create an additional incentive for Australian state and federal governments to be seen as active in promoting the bilateral relationship.

It is important to acknowledge that the Australian Indian diaspora is not one cohesive whole. Much like India's complex society, it is made up of diverse sub-groups, state and community associations. It may not naturally self-organise in a way that maximises its political or economic leverage, complicating engagement.

This chapter sets out the current disposition of Australia's Indian diaspora, how this relates to international experience, and what more Australia could do. There are four themes that emerge around which to focus efforts on leveraging the diaspora.

Improving India literacy of Australia's corporate sector

The Indian diaspora in Australia is not yet sufficiently prominent in our leading industry sectors or business associations. It can't yet play a significant role in mobilising confidence to expand trade and investment with India.

Over 8 per cent of Australia's population is born in Asia – a much higher percentage than in other Anglophone countries – yet only around 4 per cent of Australia's top 200 publicly listed companies have board directors of Asian heritage.130

Australian companies with 'Asia capable' workforces, including migrant representation at all levels of the organisation, are rare. Indeed, 67 per cent of ASX 200 board members show no evidence of extensive experience operating in Asia, while 55 per cent demonstrate little to no knowledge of Asian markets. Those that do claim immersive experience in Asia overwhelmingly rely on time spent in Singapore and Hong Kong, two markets consistently ranked at the top of the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business index.119

But this is not to presuppose that only large listed companies have a role to play. Most Indian diaspora businesses in Australia are SMEs, and they too have the capacity to be meaningful drivers of economic integration with India. It has been estimated that within three years, around 66 per cent of SMEs in countries like Australia could derive at least 40 per cent of their revenue from outside their country of operation131 – so the key is to ensure that SME growth occurs in exportable sectors of the economy.130

Encourage greater Indian postgraduate student enrolment in cutting edge fields, technologies and economic sectors where Australia is competitive

Indian postgraduate student numbers are on the rise in Australia, but most are enrolled in masters by research courses in oversupplied fields. Indeed, we may be seeing Indian students leaving their undergraduate STEMM qualifications. Australia needs to do more to promote its academic excellence.

There is a positive feedback loop between greater bilateral research collaboration and Indian perceptions of the quality of Australian educational institutions. Between 1993 and 2013, India was one of the top three source countries for Australian academics (the other two being the United Kingdom and China). Indian diaspora researchers play a disproportionately large role in Australia's collaborative efforts with India – 60 per cent of the Australia-based authors of scientific publications co-authored by researchers in India and Australia were of Indian descent. So the current enrolment bias among Indian students towards masters by coursework degrees is likely to limit the future of research collaboration between Australia and India.

Place diaspora achievement and entrepreneurial ventures at the forefront of our bilateral engagement

India puts a large effort into working with its diaspora. It no longer considers overseas migration of Indian skilled professionals as 'brain drain', but rather as a 'brain circulation' that enhances India's global image and contributes to 'brain gain' in India through innovation, investment, and business expansion. India's professional diaspora is regarded as innovative 'opportunity entrepreneurs'132, who forge links, invest in, and mentor high value technology ventures between their countries of residence and origin. The diaspora are now seen as integral to India's growth story and there is strong receptivity within India to a 'diaspora forward' engagement strategy.

The AIBC, the leading current diaspora business organisation, has limited presence among peak industry bodies in India and Australia. While it serves as a representative body for the Indian business diaspora and participates in bilateral trade delegations, it does not have an explicit advocacy strategy to promote diaspora presence and leadership in the key chambers of Australian commerce and industry. It has not yet developed a profile of diaspora entrepreneurship in Australia's competitive industry sectors or coordinated with Indian counterparts to attract Indian mid-size enterprises to invest in tie-ups in these sectors. The 2018 AIBC constitutional amendments should help drive change over time.

More could be done in Australia to incubate and mentor diaspora entrepreneurs in fields where Australia has a competitive edge. The IndUS Entrepreneurs (TiE) group has a proven track record assisting entrepreneurs of Indian origin in the United States with mentoring, incubating, networking and venture capital financing. TiE chapters exist in Australia, but they maintain a low profile. Another useful focus for engagement will be diaspora professional groups, including a number that already exist in the professional services.

Encouraging greater participation in politics and civil society

The Indian diaspora in Australia lacks presence and influence in higher levels of state and federal politics, policymaking, universities, large corporations and peak industry bodies.129 Australia needs to do more to encourage diversity in these areas. Increasing political representation in Australia on the part of the Indian diaspora will be a potent driver of the bilateral relationship.

What can we learn from the evolution of Indian diaspora communities globally?

India has the largest diaspora population in the world, with over 13 million Indians living outside the country and 17 million people of Indian origin spread across 146 countries.98 They range from long-standing populations in places like the Caribbean, Fiji, South and East Africa and Malaysia, to the very large numbers now building the Gulf States.

The Indian diaspora of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada comprise a relatively small proportion of total population, but they have emerged as powerful economic players in their own right and in their ability to strengthen economic ties with India.

Each of these countries has experienced a surge in the migration of highly skilled Indian professionals and students with tertiary and higher educational qualifications since the 1990s, and has nurtured this talent and its potent advocacy for enhanced economic ties with India.

In general, the Indian diaspora in these countries are recognised for contributing to innovation and entrepreneurship, competition, economic growth and job creation.

In particular, their prominence in leading industry sectors and establishment of dynamic professional and business associations has helped build trust and understanding to expand trade and investment with India. They provide insights into India's business norms, cultural landscape and language diversity, and facilitate connections with state governments and industry bodies. They lobby their governments for stronger political and business alliances with India and promote frequent visits, delegations and conferences across government and industry. And their diverse perspectives help support the uptake of new technologies and processes.

There are common factors that contributed to the emergence of Indian diaspora as powerful economic players in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Singapore:

- each had strong reputations in India as countries offering good career, not just migration, opportunities

- their success in attracting talent, with high numbers of international students enrolled in STEMM majors and professionals employed in STEMM, using targeted visa categories

- top universities offering scholarships that set a high quality benchmark for the reputation of the receiving country and set the trend for subsequent generations of high-achieving Indian students

- the success of these high-achieving students establishing the reputation of Indians as highly-skilled researchers and hardworking professionals

- the visible presence of diaspora achievement in technology, innovation, business, senior corporate roles and in government

- the dynamism of the Indian diaspora in entrepreneurship

- Indian diaspora professional associations active in building networks with industry and mentoring Indian students

- the increasing influence of the diaspora in domestic politics.

CASE STUDY: Australia's Indian Diaspora at a glancexxxiv

- 675,658 claimed Indian ancestry in 2016, constituting 2.8 per cent of the Australian population.

- Indian-born population amounts to 455,389 or 1.9 per cent of the Australian population.

- It is the fourth largest, and one of the fastest growing, migrant communities in Australia, growing at 10.7 per cent per annum on average between 2006 and 2016. Indian-born population is expected to overtake the Chinese-born population by 2031, reaching 1.4 million.128

- 48 per cent of the Indian-born population are Australian citizens – students form one-third of the India-born, non-citizen resident population.

- Indian-born population is almost three times as likely as the wider Australian community to hold a bachelor's or higher degree (58 per cent of the Indian-born population as compared to 22 per cent of the wider community).123

- Around 88 per cent of the working age, Indian-born population are employed, 61 per cent in full-time work, 27 per cent in part-time work.123

- The personal, family, and household median incomes of the Indian-born population are higher than that of overseas-born, Australian-born, and national populations

- Indian-born migrants are the second-highest tax-paying diaspora after UK-born migrants

- they contributed $7.9 billion in 2011–2012 and $11.9 billion in 2013–2014 in taxation revenue.

- Indian-born migrants are the second-highest tax-paying diaspora after UK-born migrants

- Predictably, Australia's Indian dispora population is concentrated in the larger states of Victoria and New South Wales, as illustrated by Figure 29. Indian-born residents account for around 3 to 4 per cent of the population in Perth, Sydney and Melbourne, and around 2 per cent in Brisbane and Adelaide.

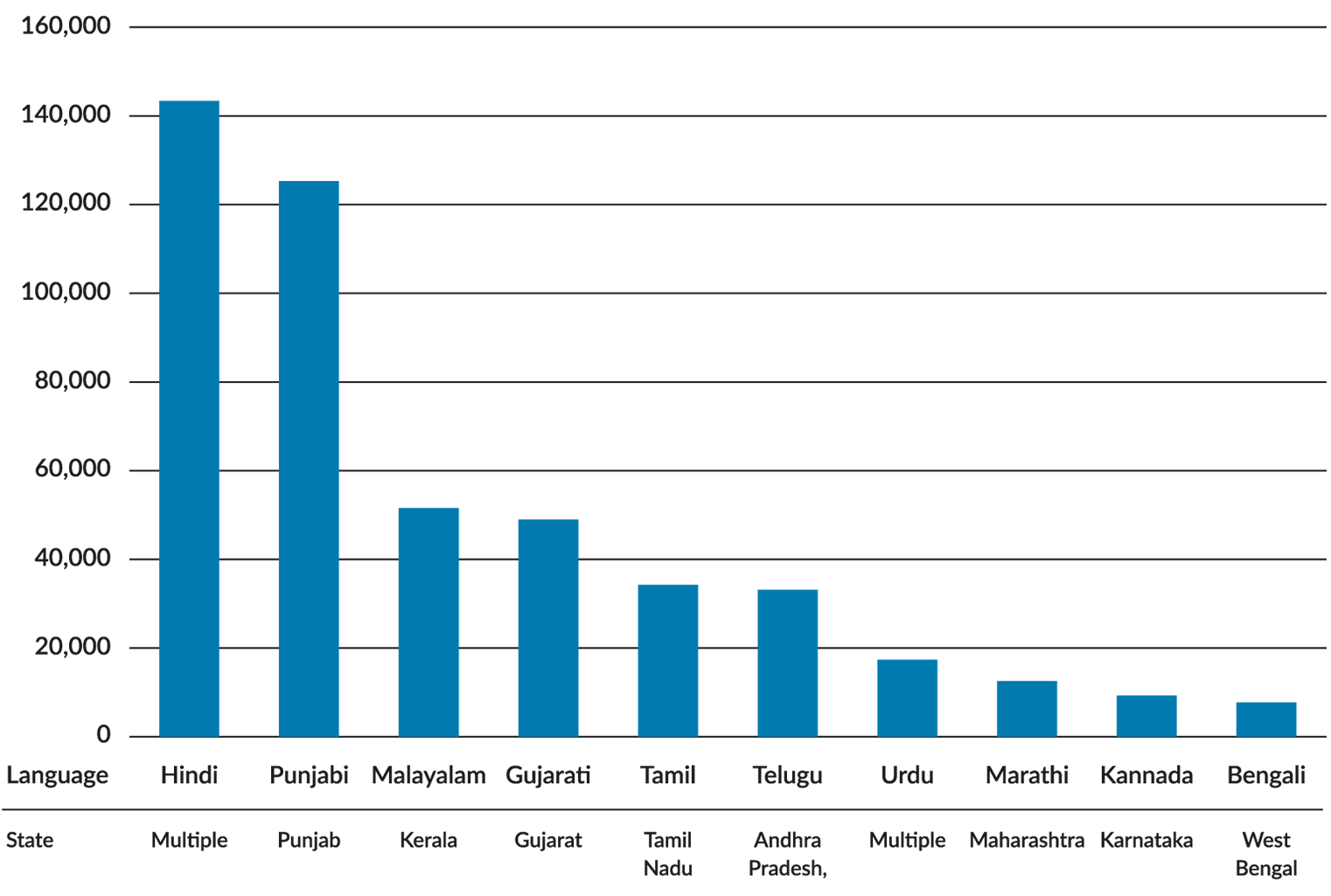

- Figure 30 outlines the number of speakers of a number of Indian languages in Australia, providing an indicative picture of the diaspora's Indian states of origin. What is immediately obvious is the large number hailing from Punjab, Gujarat and Kerala.

Figure 29: People claiming Indian ancestry by Australian State

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2016 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2016.

Figure 30: Indian languages spoken in Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2016 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2016.

By Comparison...

The United States

- There are around 4 million people of Indian origin in the United States133, representing 1.2 per cent of the total population.

- Indian-Americans have higher levels of education overall than both foreign and US-born populations

- 77 per cent of Indian-Americans aged above 25 years have bachelor's degree or a higher qualification compared to 29 per cent of all immigrants and 31 per cent of US-born adults (2015)

- more than half of these have masters or doctoral degrees in STEM-related disciplines and professional fields.133

- It is estimated that 68 per cent of Indian-Americans participate in the labour force (2015 estimates), slightly higher than the overall foreign (66 per cent) and the US-born populations (62 per cent)

- 73 per cent of Indian-Americans are employed in high-skilled STEMM occupations and management, business, finance, law, and higher education, compared to 31 per cent of both foreign-born and US-born populations.

- One-third of all immigrant-founded companies were founded by the Indian diaspora with one-quarter of immigrant-founded transnational engineering and scientific companies were established by Indian diaspora, most notably in Silicon Valley.130

- Indian-Americans are among the highest-earning ethnic groups per capita in the United States, with more than 66 per cent earning over USD100,000 per annum

- median annual household income for Indian-Americans is much higher (USD107,000) than the overall foreign (USD51,000) and US-born populations (USD56,000).133

The United Kingdom

- In 2011, there were 1.45 million British Indians, constituting 2.3 per cent of the total population, an increase of over 400,000 from 2001

- India and Poland are the most common countries of birth outside the United Kingdom.123

- More than 25 per cent of people of Indian origin in the United Kingdom attend elite universities, and enter professions such as medicine, law, pharmacy and accountancy.

- The unemployment rate for Indian migrants is lower than for other ethnic groups in the United Kingdom134

- in 2011, the Indian-born population was among the leading diaspora communities in highly skilled occupations such as doctors, engineers, solicitors, chartered accountants, academics, and ICT experts (199,000)

- Indian IT professionals comprise 60 per cent of all foreign IT professionals arriving in the United Kingdom

- around 6 per cent of all doctors in the National Health Service are Indian135 and Indians account for 40 per cent of health-related retail sector and small and medium-scale businesses.

Canada

- In 2016, there were 1.4 million Indo-Canadians, constituting around 4 per cent of the population.

- Around 45 per cent of Indo-Canadians hold university degrees compared to 26 per cent for the overall population.

- The employment levels of Indo-Canadians are higher than the overall population. Over 75 per cent of Indian migrants to Canada are highly educated professionals, skilled workers, businessmen and entrepreneurs.

- However, there are disparities between employment match rates for professionals born and educated overseas as opposed to born and educated in Canada

- for physicians born and educated abroad, the employment match rate is 42 per cent, but that increases to 80 per cent for Canadian-born and educated physicians

- there are similar gaps for nurses, engineers, accountants and teachers.136

- Indo-Canadians tend to receive lower incomes than the national average.137 However, most of the post–1990 Indian migrants also show significant economic mobility over three to five tax years of their arrival138

- almost 20 per cent of all high income Indo-Canadians over the past decade (to 2017) have gained their wealth by becoming entrepreneurs, including in mining, software, health care technology, real estate and hotel industries.

Singapore

- Indians are the third largest ethnic group in Singapore after Chinese and Malays and constitute approximately 7.4 per cent of Singapore's resident population139

- of the 1.65 million foreigners in Singapore, 21 per cent are Indian expatriates holding Indian passports

- Singapore has longstanding diaspora ties with southern Indian states in particular, with regular mobility and circulation of businessmen between the two countries.

- Around 60 per cent of Indian migrants to Singapore are professionals in financial services, IT, construction and marine sectors, owners of small and medium businesses, and students

- from the 1990s, Indian professionals were offered permanent residency in Singapore and full rights (excluding the vote) to work, start businesses, and access government housing

- Singapore attracts talented Indian students with postgraduate and doctoral scholarships for its leading universities.

- Many graduates of India's prestigious IITs and IIMs have gone on to establish businesses in Singapore in IT, commodities trading, shipping, agribusiness and start-ups in new service industries like multimedia marketing and e-commerce.

So how is Australia's Indian diaspora experience different?

As with experience in comparable countries, the Indian diaspora in Australia is highly educated, employable and wealthy. The initial track of Australia's Indian diaspora story mirrored the experience in other countries, but the employment of Indian migrants over the past decade has charted a different course.

The introduction of the Migration Act in 1966 enabled larger numbers of Indians to migrate to Australia.128 As elsewhere, Indian immigrants to Australia in the 1960s and 1970s were mainly highly-qualified professionals in well-paying jobs in medicine, engineering and business. Many who came on Colombo Plan scholarships to study in Australian universities subsequently returned to settle in Australia and pursued successful careers.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Indian engineers and IT specialists arrived under the skilled-migrant program and settled to pursue careers in the country's emerging knowledge-based economy.

Figure 31: Indian migration to Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2016 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2016.

In Australia, skilled migration and education-related migration from India increased dramatically between 2006 and 2016, more than doubling the numbers of the India-born population123, making the Indian diaspora a relatively young community compared to the United Kingdom, Canada, Singapore and the United States. It's clearly no coincidence that this expansion mirrored the period of significant labour shortages during the mining construction boom – spread roughly equally between professional and non-professional sectors.

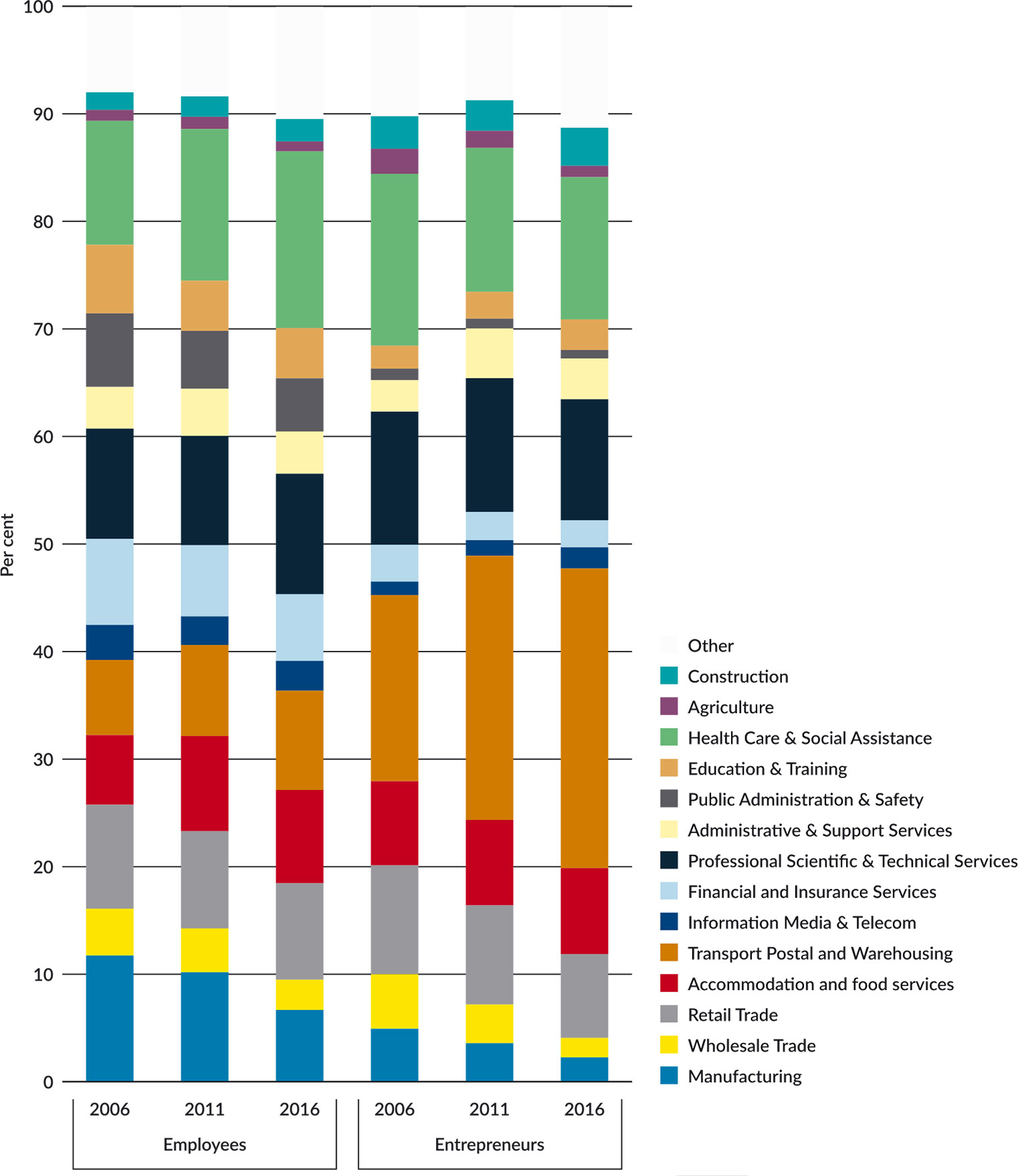

An analysis of where the Indian-born population was employed, and in which sectors they are building businesses, provides an indication as to whether we are truly maximising the potential of this community as a driver of Australian growth and innovation.

As we would expect, employees of Indian origin were broadly distributed across the economy during the period of low unemployment generated by the mining boom.

CASE STUDY: Indian diaspora success in the United States information technology industry

The success of the Indian diaspora in Silicon Valley and their contribution to the successful growth of the Indian IT industry has been globally recognised by scholars and policymakers. They are regarded as the exemplar for industry and diaspora-induced economic development that mutually reinforces growth in trade, investment and knowledge-exchange between the two countries.

Silicon Valley and Bengaluru rose synergistically. From the onset of Silicon Valley's rapid growth, it became a destination of choice for Indian technology graduates, many of whom remained in the United States after obtaining their degrees and rose to senior positions in leading Silicon Valley technology firms. In 1986, the Indian Government introduced the Computer Software Development and Training Policy which liberalised access to technology and software tools, invited foreign investment, and supported access to venture capital. It invited leading industry professionals of the United States Indian diaspora to advise the Department of Electronics and to invest in the development of the Indian software industry. The diaspora professionals actively contributed to policy reform in areas of Indian telecommunication regulation, science and technology policy, reform of educational institutions and capital markets. This led to the growth of Indian software solution companies such as TCS, Infosys and Wipro.

Diaspora professional associations such as the Silicon Valley Indian Professional Association and The Indus Entrepreneurs played, and continue to play, a significant role in this. They helped forge a common, pan-Indian identity in the United States. They served as mentors for Indian engineers studying and working in the United States and played a key role in ensuring international quality and performance standards, including providing new business contacts and new markets in both countries. They collaborated with Indian industry organisations like CII, NASSCOM and IIT Alumni Associations to celebrate technology entrepreneurship in the United States and India. They played an important role in mobilising their networks to raise venture capital and functioned as angel investors for start-ups and social enterprises. And the dynamism of the United States Indian diaspora in founding engineering and technology companies in turn proved a major attraction for Indian investors in United States industry.

About 30 per cent of India-born employees were in food and accommodation services, retail and wholesale trade, and transport services; roughly 10 per cent work in manufacturing, agriculture and construction sectors. Just over 50 per cent were employed in professional, managerial, and technical service occupations, with the main industry categories for India-born employees being IT systems design and enabled services, accountancy, medicine and health services (Figure 32).

The major change between 2006 and 2016 in sectors of employment for Indian-born employees was a decrease in those employed in manufacturing and an increase in those employed in health care and social assistance.

Figure 32: Indian-Born employees and entrepreneurs by industry

Source: 1) Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2016 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2016. 2) Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2011 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2011. 3) Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2006 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2006.

Driving Australian entrepreneurship?

The story of missed opportunity is more stark in the Australian diaspora's entrepreneurial journey. Australia's Indian diaspora shows the same entrepreneurial spirit demonstrated elsewhere. Between 2006 and 2011, businesses owned by Australia's India-born population rose by 72 per cent, compared with a 40 per cent increase for those born in China. However, as Figure 32 shows, the sector experiencing the most significant growth in Indian diaspora entrepreneurship between 2006 and 2016 was the transport, postal and warehousing sector. While embracing the entrepreneurship and personal drive that has seen the surge in self-employment in this sector – this is clearly not going to drive Australia-India economic integration.

Students – a missed opportunity

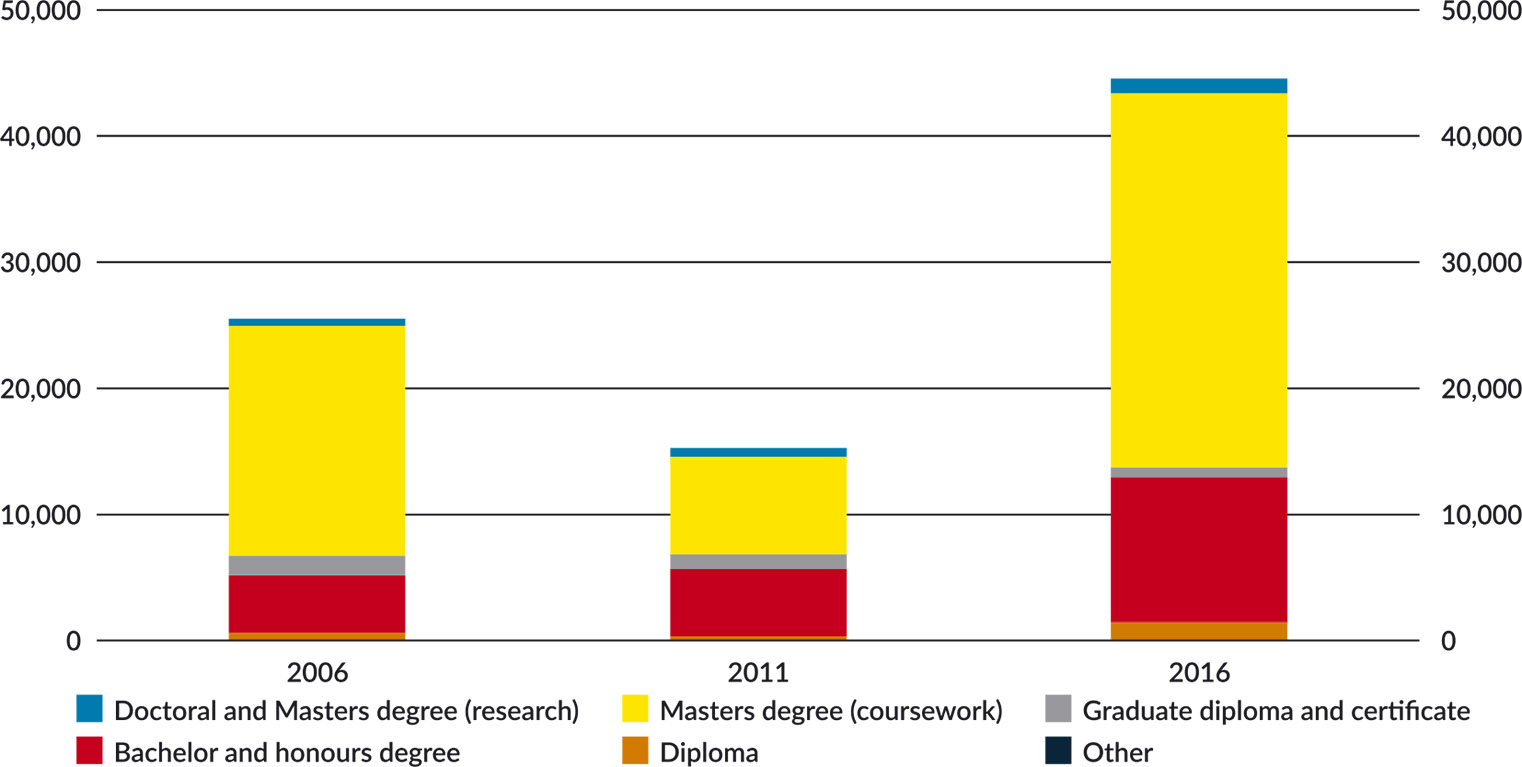

The trends in Australia's student intake from India show a similar missed opportunity. Indian students form the second largest international cohort (15 per cent) in Australian universities, following students from China (34 per cent). The numbers of Indian international students in postgraduate courses in Australian universities have been growing rapidly since 2014. However, masters by coursework is by far the most popular option for Indian students (70 per cent), followed by bachelor degrees (22 per cent), and has been growing rapidly since 2014. Only 2 per cent of Indian students in Australia pursue doctoral degrees.

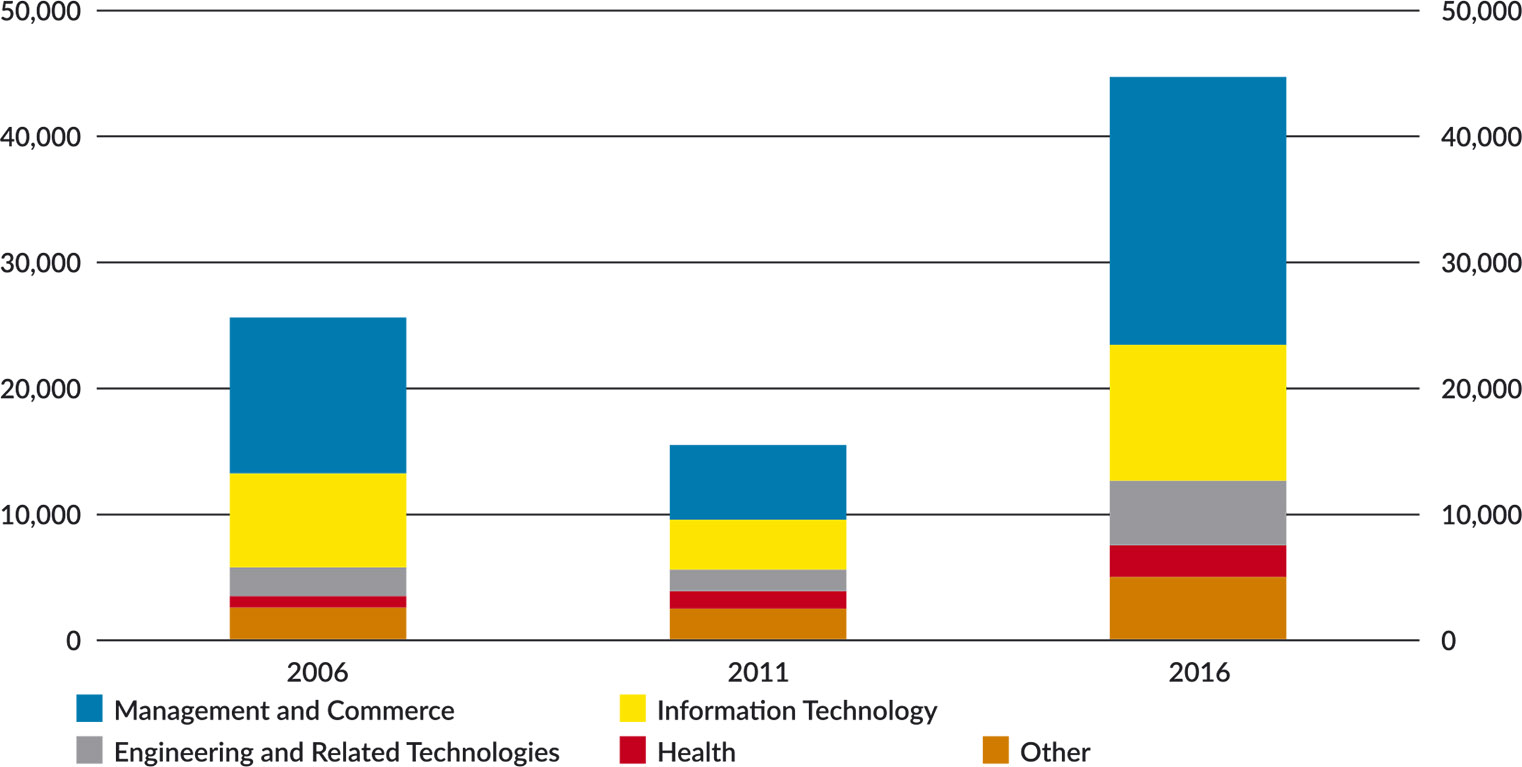

Most of those enrolled in masters courses graduate in oversupplied fields140, rather than in programs focused on advanced fields, technologies and economic sectors where Australia has a global edge. The top four preferred fields of higher education for Indian students are: Management and Commerce (48 per cent), IT (24 per cent), Engineering and Related Technologies (11 per cent), and Health (6 per cent).

Indian students comprised a similar proportion of global international students in the United States (13.6 per cent), but this is maintained at doctoral level (14 per cent of all temporary student visa [F–1] holders pursuing doctoral degrees) and about 80 per cent were enrolled in STEMM majors (MPI, 2017). According to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, 85 per cent indicated their intention to stay in the United States upon completion of their studies – a significant injection of intellectual firepower.

Significantly, 70 per cent of a representative sample of Indian students enrolled in post-graduate study in Australia in 2016 and 2017 had undergraduate qualifications in STEMM. We need further research to determine whether these students ultimately return to STEMM careers, or whether these skills are lost to the Australian economy.

Current enrolment biases among Indian students towards masters by coursework degrees present a risk also to the future of research collaboration between Australia and India.

Between 1993 and 2013, India was one of the top three source countries for Australian academics (the other two being the United Kingdom and China). In 2014, 30 per cent of all postgraduate researchers were international students, with the figure higher in the STEMM disciplines of engineering (54.2 per cent), information technology (51.5 per cent), agriculture and environment (45.6 per cent) and natural and physical sciences (36 per cent).

Figure 33: Indian student enrolments in higher education by level of study

Source: Australia India Institute. Working Paper Commissioned for the India Economic Strategy.

Figure 34: Indian student enrolments in higher education by broad field of education

Source: Australia India Institute. Working Paper Commissioned for the India Economic Strategy.

In the decade to 2017, joint research papers between Indian and Australian researchers have doubled, indicating increased collaborations. Unsurprisingly, Indian diaspora researchers play a disproportionately large role in Australia's collaborative efforts with India. Of all scientific publications co-authored by researchers in India and Australia, a large majority of the Australia-based authors (60 per cent) were of Indian descent. Enhancing the reputation of our education system and building collaborative research and innovation ecosystems between Australia and India depends on a pipeline of high-performing students and academics.

Australia's Indian diaspora – a trading edge?

There is no noticeable correlation between the overall growth in trade with India and increase in migrants from 2006 to 2016 (Figure 35). Certainly, there appears to be no direct relationship between Australia's major exports to India and the industry categories in which Indian migrants have been employed during this period.

There may be some correlation between India's exports to Australia and the movement of professional staff generating these exports. Around 30 per cent of Indian exports to Australia comprise services, of which 'professional, technical and other business' make up one-third. This services export category most likely correlates with the rising numbers of Indian migrant employees and entrepreneurs, particularly between 2011 and 2016, categorised under professional, scientific, and technical services (see Figure 32; mostly in IT and business solutions).

Figure 35: Changes in bilateral trade and investment and Indian-Australian diaspora population

Source: 1) Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). 2016 Census. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2016. 2) Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (AU). Services Trade Access Requirements Database. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2017

Recommendations

Australia tends not to use its domestic diaspora groups strategically to advance its foreign policy and trade interests. This must change. The opportunity is ripe for Australia to capitalise on its Indian diaspora, which should be seen as a national asset in the bilateral relationship and deployed accordingly.

The challenge for the Australian Government is fine-tuning the settings across immigration, education, foreign and trade policy to leverage the Indian diaspora. In a broad sense, the settings are performing well. Australia ranks 6 out of 100 countries on the ability to grow, attract and retain talent.141 The fact that migration has delivered an economic dividend for Australia is in large part due to policy settings which favour migrants of working age who have the necessary skills to contribute to the economy. In any case, there are limits to what government can do to some of the settings that are inherently demand-driven, for example, the temporary skilled migration program.

However, the government should deepen its engagement with Australia's Indian diaspora as a resource to advance economic links and build transnational networks for trade, investment and innovation.

We need to shift our thinking about the diaspora away from the multicultural narrative, important as that is, and towards seeing the Indian diaspora as a network which can open doors, help navigate Indian business culture, enhance the community's understanding of contemporary India and contribute to Australian public diplomacy in India.

- 88.Attracting the right student and professional talent, including in the STEMM fields, that will drive Australian economic growth

- 88.1Attract talented and highly competitive graduates from top-level Indian higher education institutions with scholarships and other incentives linked to career advancement and entrepreneurship opportunities in such sectors [see Chapter 3: Education Sector].

- 88.2Maintain skilled immigration categories for attracting highly talented professionals, such as the Global Talent Scheme [see Chapter 16: Trade Policy Settings].

- 88.3Sharpen the focus of both migration and education visa streams towards long term growth drivers in the Australian economy, in particular STEMM.

- 89.Building diaspora-focused connections between Australia and India

- 89.1Support diaspora and student peer-to-peer networks, institutional linkages and business to business organisations.

- 89.2Develop networks with diaspora professionals and companies who mentor students and create internship opportunities in key sectors, including alumni associations in India

- a pilot initiative could be a 12 month mentoring program under the CEO Forum

- diaspora and India-focused innovation ecosystems such as TiES should also be encouraged.

- 89.3Conduct an Indian diaspora industry and research mapping exercise in collaboration with university partners, diaspora alumni associations and business organisations to further quantify the reach of the Indian diaspora into the bilateral economic relationship.

- 89.4Encourage and leverage IIT/IIM Alumni organisations in Australia, in addition to Australian university alumni in India.

- 89.5Establish diaspora-led roundtables/consultative groups in each of this strategy's priority sectors and states

- this could be led by DFAT in conjunction with relevant line agencies and Australia-India business chambers.

- 89.6Improve mechanisms for linking the research and business diaspora for the commercialisation of research and development.

- 90.Giving prominence in the bilateral relationship to achievements and innovation in the diaspora

- 90.1Leverage India's 'brain circulation' narrative of the diaspora by ensuring Indian diaspora participation is prominent in bilateral engagement.

- 90.2Increase the visible presence of diaspora achievement and leadership in Australia's competitive growth sectors.

- 90.3Engage CEOs of successful Indian diaspora businesses, Indian diaspora professionals in high-level executive positions in Australian companies, and leading Indian diaspora researchers at Australian universities more closely

- including by encouraging their participation in bilateral dialogues, delegations, and business to business engagement between India and Australia

- 90.4Support efforts by Asialink, the Diversity Council Australia and others for greater Indian diaspora representation in organisational structures and on boards.

- 90.5Ensure visiting Indian delegations spend time both with the broad Indian diaspora community and with Indians of notable achievement.

- 90.6Celebrate and showcase achievement and entrepreneurship within the diaspora community, through the India Australia Business and Community Awards and similar initiatives.

- 90.7Lobby the Indian Government to regularly host the regional biennial Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (Overseas Indian Day) convention and awards ceremony in Australia.

- xxxiv Based on the 2016 Census data unless otherwise specified.