Summary

- The opportunities for Australian investment in India are significant. Out to 2035, India's policy framework on foreign investment will continue to open, its business environment will continue to improve and its growth story will provide an active diversification strategy for investors.

- India is keen to attract foreign investment. It has made substantial progress in liberalising foreign investment policy settings. The stock of inward and outward direct and portfolio investment has grown from a little over 1 per cent of GDP in 1990 to more than 30 per cent in 2017. India's reforms to foreign portfolio investment (FPI) are impressive and ongoing.

- However, India will need to further liberalise investment frameworks and be willing to offer greater certainty to investors if it is to attract the capital required to boost productivity, create employment opportunities, and deliver real improvements to living standards. In recent years India has cancelled and sought to renegotiate its Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs).

- Australian direct investment in India is under-developed. The converse is also true. Major investment opportunities are emerging or will appear in a range of sectors that match Australian strengths. Similarly, there is potential for large-scale Indian direct investment in Australia, including to address security of supply in support of India's energy and infrastructure needs.

- For Australian investors the key messages about what it takes to be successful are consistent. Businesses must make use of local knowledge about the business environment, find an appropriate local partner and be willing to be in India for the long term. This recipe is seeing companies from other countries successfully invest in India.

- Direct investment in India is challenging due to its business environment and regulatory unpredictability. The Central Government's reforms are only part of the picture. Many of the permits and approvals required for investment are in the hands of state and local authorities, where delays and setbacks remain common. Over the longer term, reform among the Indian states will improve the investment climate.

- Stocks of Australian portfolio investment in India have increased from a very low base. India may be appealing to Australian funds seeking to diversify the geographic and asset class exposure of their portfolios.

- The Australian Government plays no part in directing private investments but it has a role familiarising investors with markets in both directions. Changes to protect investors and facilitate investment are required and replacing the terminated bilateral investment agreement should be a high priority. There is an increasing role for investment vehicles which help manage risk and deliver steady returns.

- While Australian investors will make their own commercial decisions, increasing Australian investment stocks in India would correspond with deeper economic integration contributing to increased Australian trade and competitiveness. The target set out in this report of India becoming the third largest destination in Asia for Australian outbound investment is ambitious. But if India's growth and regulatory reform continue at pace and if Australian investors shift focus to India, the target is achievable.

Introduction

While there is a firm basis to expect average GDP growth of 6–8 per cent, as set out in Chapter 1, there is nothing pre-ordained about India's modernisation.

India is traditionally a labour-surplus economy with a severe shortage of productive capital. Increasing and maintaining steady flows of investment is vital for India's industrial development and facilitating productivity growth.

India's economic growth will be just as dependent on productive investment as it will on an increasingly larger and richer population and greater access to international markets. As in the past, the great bulk of this investment will be sourced from domestic savings. But a significant part – possibly 4–6 per cent of gross domestic capital formation judging by trends since 2000 – might be from FDI, making FDI a significant component of India's modernisation and development. But policy makers will have to increase their emphasis on enabling investment flows for this to happen – the gap between India's investment and trade flows lags well behind global benchmarks (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Global Benchmarking of Indian Trade & Direct Investments to GDP

Source: 1) The World Bank. Balance of Payments Statistics Yearbook and data files. The World Bank; 2018. 2) The World Bank. World Bank National Accounts Data. The World Bank; 2018. 3) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. National Account data files. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2018.

Securing foreign capital will require India to implement further economic reforms and improve its investment climate. This chapter is organised in four parts:

- How India has increasingly drawn on foreign direct and portfolio assets to help fill the gap between its domestic savings and investment requirements.

- The factors that encourage and limit flows of FDI in India, including for Australian investors.

- The factors that encourage and limit flows of FPI in India, including for Australian investors.

- What could affect Australia's future investment relationship with India.

Overview of India's investment integration with the world

India's external financial assets and liabilities have grown from a little over 1 per cent of GDP in 1990 to more than 30 per cent in 2017 (Figure 13). Outward FDI has also become prominent in the last decade or so, though portfolio investment abroad is negligible. Outward FDI flows are much lower than inward FDI but are growing and significant in sectors like minerals and energy.

Figure 13: Financial Integration over Time: Direct and portfolio assets and liabilities

Source: 1) Adapted from Lane P, Milesi-Ferretti G. Working Paper of the International Monetary Fund. International Monetary Fund; 1999. 2) Reserve Bank of India (IN). New Delhi IN: Government of India; 2017

Over the past two decades, capital inflows have been prominent in areas like telecommunications, transport infrastructure and information technology. This has helped boost productivity and create employment opportunities through transfers of technology and skills.

Regulatory improvements have supported these trends. Foreign investors can now, in principle, invest in most sectors with minimal government policy barriers (though transaction costs on the ground still remain high). Investment in government and corporate bonds has also been deregulated gradually in the last few years.

Despite this growth, India's investment rate as a proportion of GDP is relatively low compared to some other major Asian economies (Figure 14). This is related to India's services-led growth which requires less capital per unit of output than heavy manufacturing. The recent downward trajectory highlights India's struggle to attract investment.

Foreign investment is still impeded by high levels of corporate debt, financial sector stress and regulatory and policy challenges.

Figure 14: Investment Rate

Source: World Development Indicators | DataBank [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators)

Non-performing assets

Weak credit growth and India's high cost of capital are slowing investment flows. This is driven primarily by the level of NPAs on public and, to a lesser extent, private banks' balance sheets. On a year-on-year basis, gross NPAs now stand at nearly one-tenth of all loans (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

NPAs at this level put pressure on banks' profitability, constrain their capacity to lend and therefore limit the non-bank sectors' ability to invest. With investment and credit growth highly correlated, NPAs are perhaps the largest single factor hindering investment growth. In a bid to mitigate these pressures, in October 2017 Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced a public sector bank recapitalisation plan of Rs2.11 trillion (approximately AUD40 billion).

While this should spur lending, without associated reform any positive outcomes may prove short lived. Indian taxpayers have bailed out India's state-run banks on a number of occasions. Systemic reform is needed, involving aligning public banks' incentives more closely with profitability and sustainability and strengthening the capability of regulatory authorities.

Figure 15: Indian Non-Performing Loans

Source: International Monetary Fund. Global Financial Stability Report. International Monetary Fund; 2018

Figure 16: Indian Commercial Credit to Commercial Sector

Source: The high economic costs of India's demonetisation [Internet]. The Economist. 2017 [cited 3 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21713842-benefits-withdrawing-86-rupees-circulation-remain-elusive

CASE STUDY: Suzlon: Tapping into Australia's wind potential

India's Suzlon Group started Australian operations in early 2004 having identified Australia as one of the world's largest untapped wind generation markets.

Suzlon is reaping the rewards of being an early mover - Australia is now one of its key markets. Suzlon group commands approximately 17 per cent of the Australian market share by installation with a footprint of 764 megawatts (MW) and a cumulative annual turnover of $1.7 billion since 2005.

Suzlon's Australian operations are managed locally and all decision-making activities are performed locally which allows for quick responses to stakeholders. Suzlon has also established an Australia-based 24/7 monitoring centre which gives a competitive advantage in the market.

Suzlon's operations contribute to jobs and growth in regional communities. Each Suzlon wind farm has been constructed employing a local work force. This had led to the creation of over 325 permanent jobs and 500+ constructions jobs across nine wind farms in NSW, Victoria and South Australia. The technical nature of Suzlon's business has also created the opportunity to provide skill enhancement for local employees and contractors, improving Australia's long term skills base.

Established in 1995, Suzlon Energy is present in 18 countries across 6 continents and is one of the leading global renewable energy solutions providers. With a support network of over 8,500 employees of diverse nationalities, Suzlon has one of the largest in-house research and development capabilities with facilities in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and India.

Risk and reward in India

India is a relatively high-risk country for investors with its complex federal system of government, bureaucratic obstacles and arbitrary interventions in the market. Particular risks stem from the unequal playing field between ordinary private investors and state owned enterprises or well-connected family conglomerates, labour laws that prevent efficient firms from growing and inefficient firms from restructuring, and land laws that can tie up land-intensive projects for years. In addition, many of the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) cases against India (see section on options for investment protection below) stem from problems with India's domestic investment regime for foreign investors.

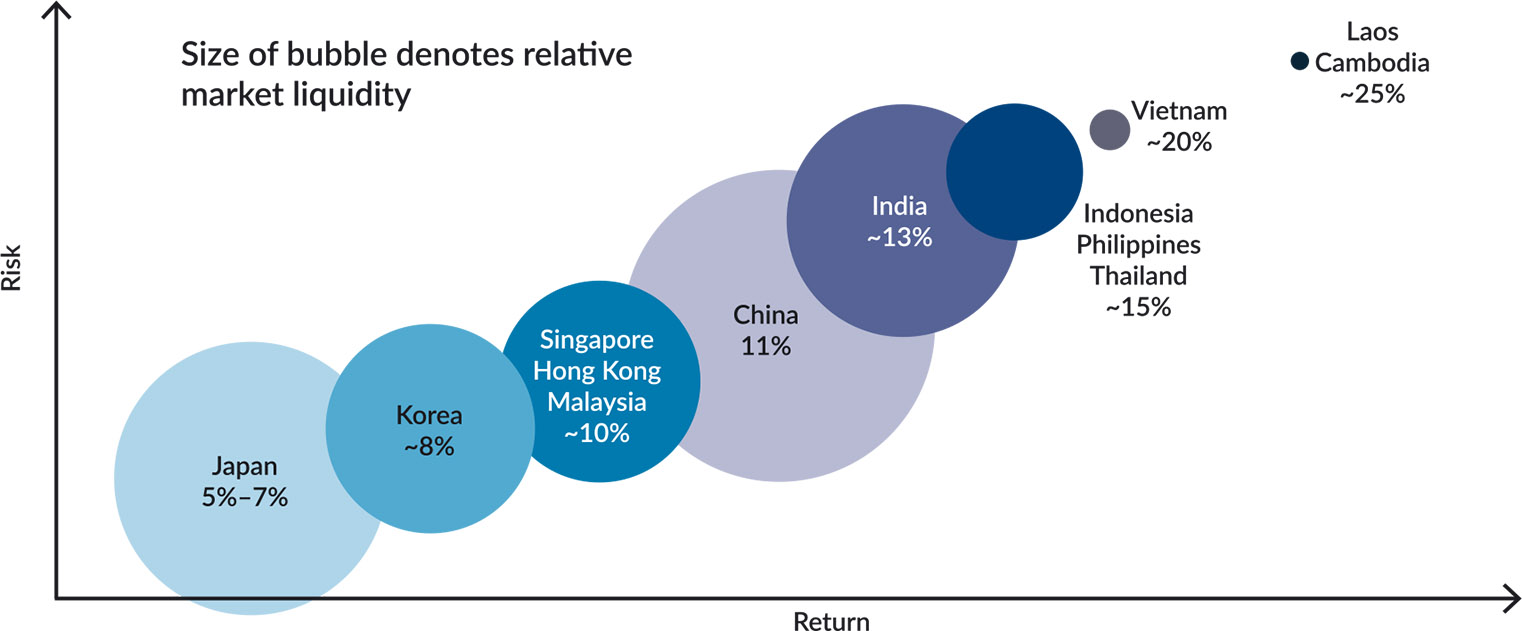

Significant reform is occurring, including through new insolvency and bankruptcy laws. The different tiers of government have ambitious investment programs and even intractable issues like land reform are being advanced in some states. But until enough incremental reforms accumulate, the number of commercially attractive projects will remain limited as investors look for higher returns to compensate for the risk level. Figure 17 shows India's risk/return ratio relative to other Asian infrastructure investment destinations.

Figure 17: Estimated Internal Rate of Return, Risk and Liquidity of Asian Infrastructure Markets, 2017

Source: Macquarie Capital. Meeting the Challenge - Infrastructure Development in Asia. Macquarie Group Limited; 2018.

Foreign direct investment

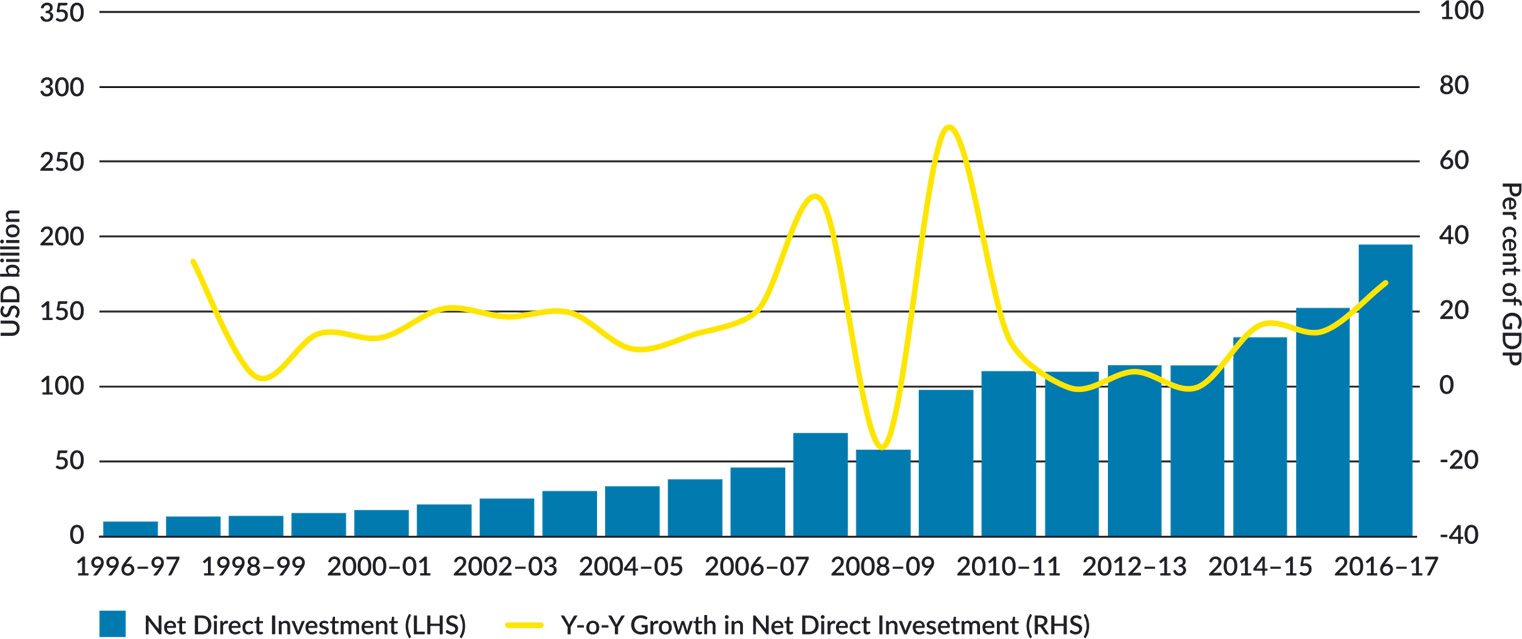

Attracting FDI is a chief priority of the Indian Government at all levels. India considers FDI a less erratic source of capital than FPI. Over the last decade India has been remarkably successful in increasing the stock of inwards FDI (Figure 18 and Figure 19). Stocks have grown by nearly 19 per cent per year over the past 20 years. This has occurred in the context of incremental trade and investment liberalisation and efforts to attract direct investment. Notable reforms include: raising foreign equity limits across many sectors; diluting the most onerous provisions of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act; allowing automatic FDI approvals in most sectors; tax reforms; capital market liberalisation and interest rate deregulation.

Figure 18: Net Inwards Foreign Direct Investment Stock, USD billion

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual, 1970–2016. Geneva: World Trade Organisation; 2016

Figure 19: Year-on-year Growth, Net Direct Investment Stocks

Source: 1) Reserve Bank of India (IN). New Delhi IN: Government of India; 2017. 2) Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (AU). Unpublished internal calculations. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2017.

These trends have contributed to India attracting investment from 155 countries between April 2000 and March 2017, across multiple sectors, particularly manufacturing and communication services.22 Well developed and more reform-minded states, including Maharashtra, Delhi National Capital Territory, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh, have attracted over 70 per cent of these inflows since 2000.22

Invest India, India's investment promotion agency, seeks to promote and facilitate inward (and outward) direct investment and provide policy inputs into FDI settings. Invest India also works with Indian states to advise them how to refine their areas of competitive strength when seeking foreign investors.

Most FDI applications are now made via a single window portal run by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion and subject to compulsory approval provisions. Restrictions such as foreign equity caps, divestment conditions and lock-in-periods are being scaled back across sectors.

Despite these improvements, real challenges remain in converting potential FDI in India into investment on the ground, and into the sectors in which it is needed. The three most limiting factors are:

- India's challenging business environment which produces a shortage of projects with commercial appeal, even in those sectors that are completely open to investment. This is compounded by unpredictable government intervention.

- Equity, screening and personnel restrictions on foreign investors.

- Complete closure of some sectors to FDI, such as legal and accounting services.

Trends in Australian FDI to India

The Australian direct investment relationship with India has been weak for a long time. Just 0.24 per cent of India's total equity inflows since 2000 have been sourced from Australia.22 This should be considered in the broader context of corporate Australia's low direct investment footprint in Asia in general.

India hosted a modest 0.3 per cent share (USD1.8 billion) of total Australian direct investment stocks in 2017.21 In comparison, a traditional investment market like the United States hosted over 20 per cent of Australia's outward FDI in that year (Table 1).

| Country | $ million | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| India | 1 827 | 0.4 |

| United States | 127 291 | 21.6 |

| United Kingdom | 83 855 | 14.2 |

| New Zealand | 62 094 | 10.5 |

| Combined ASEAN economies | 38 221 | 6.8 |

| China | 13 506 | 2.3 |

| Republic of Korea | 858 | 0.1 |

The difficulty of the Indian market does not fully explain the low levels of our bilateral direct investment. More companies from other countries are successfully investing in India. And these same risks have not discouraged a sub-set of Australian companies from investing in India because they want to be closer to a major growth market or reduce costs (see Figure 20).

What seems to distinguish successful companies from the rest is the level of effort put into understanding market compliance and risk, and a sufficiently long term view in pursuing returns. It also depends on the sector and the corresponding levels of government intervention. Mining is an example with relevance to Australia. India has rich mining assets and Australia has relevant expertise, but regulatory unpredictability and difficulties dealing with the state enterprises have made this a difficult sector to secure FDI.

Australian direct investment in India should therefore rise over time with better information on market potential and as India's economic growth continues to present opportunities. Direct investment could rise appreciably if India also opens up to more trade with Australia and the rest of the world and if it comes to see an efficient international trading and investment system as an integral element of its own economic security [see Chapter 16: Trade Policy Settings].

Trade and investment tend to go hand in hand. Outward Australian direct investment can build trust, establish networks, enhance business to business ties and reinforce the competitiveness of Australian firms. Ultimately, this can support trade and reinvestments in the Australian economy. Automation and innovation are rapidly changing India's services offerings. India's services sector is moving up the value chain. Working with, and in, India is no longer about offshoring labour-intensive tasks.

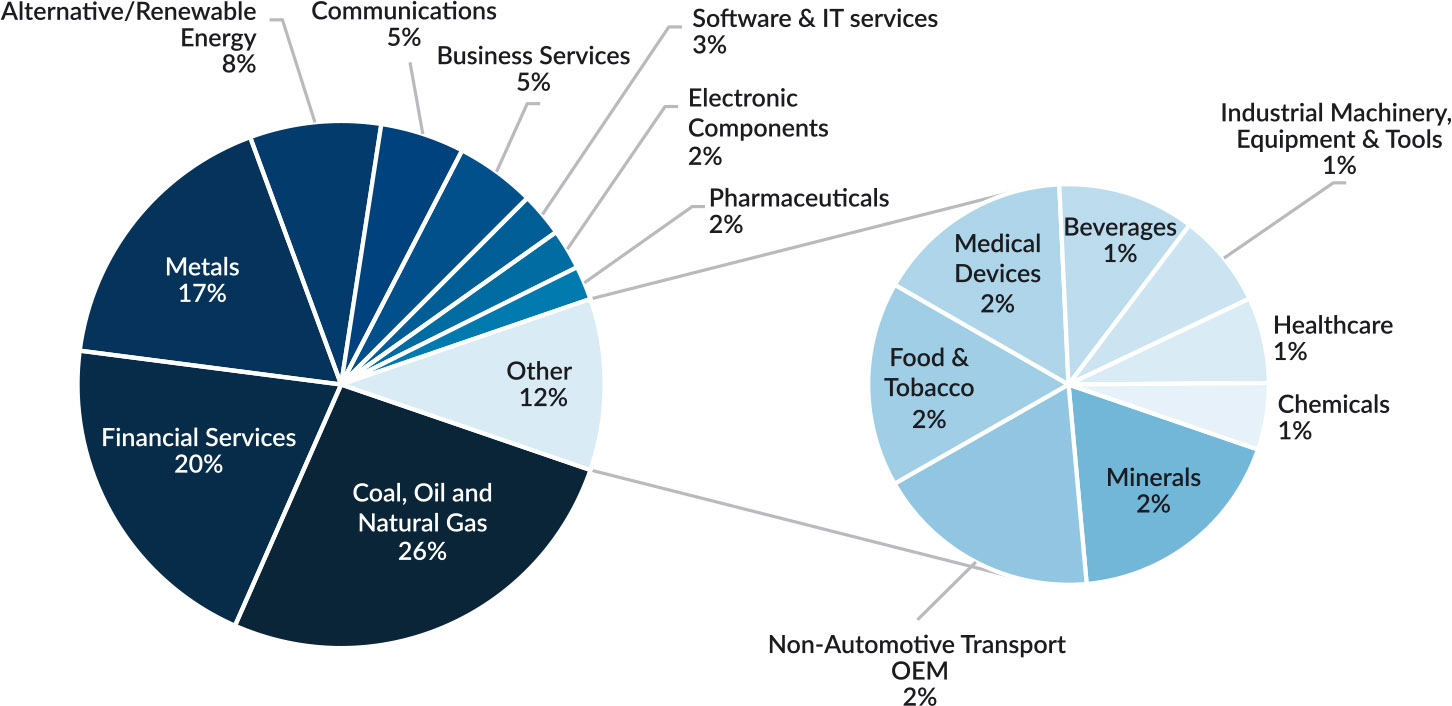

Figure 20: Australian Capex in India by Sector (January 2003 – September 2017)

Source: Fdiintelligence.com. 2018 [cited 3 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/

Trends in Indian FDI to Australia

Direct Indian investment in Australia presents a similar picture. Stocks were valued at $0.9 billion in 2016, or 0.1 per cent of total Australian stocks. There does not seem to be any discernible trend in India's intended annual capital expenditures in Australia with expenditure fluctuating markedly from year to year. What is clear is that some Indian companies are building investments in Australia from a low base in a few strategic areas: renewable energy followed by hydrocarbons, other minerals and a range of services (Figure 21). Prominent Indian investors include Tata Steel, Adani Green Energy, Suzlon Energy, BlazeClan Technologies and the Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative.

Investment from India will flow more readily as Australia's presence in the Indian market grows. The potential for large-scale Indian direct investment in Australia is real: India's outbound global investment tends to be in sectors where Australia presents many of its largest investment opportunities.

CASE STUDY: Tata Consultancy Services: Strengthening its competitive edge through Australian investment

Headquartered in Mumbai and founded in 1968, The Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) is a global IT services, consulting and business solutions company. TCS has grown to become one the world's top 10 IT companies, with a market capitalisation of more than $100 billion and a workforce of 394,000 consultants in 46 countries. As an active member of Australia's IT sector and wider business community for 30 years, TCS employs around 15,000 consultants and associates.

Australia's high technology adoption rates, local IT flair and reputation as an incubator for fresh ideas are some of the factors that attracted TCS to invest in Australia's IT sector. For instance, the company's flagship global banking product, a suite of world-class solutions for banks, capital market firms and insurance companies - TCS BαNCS - was developed in Sydney.

The company also recognises Australia's deep technology research expertise. The University of New South Wales, University of Technology Sydney and the University of Melbourne are core participants in TCS's academic alliance program, which brings together experts from the start-up, research, and corporate worlds to collaborate on innovation and solutions for TCS's customer base worldwide.

TCS is driving the agility and competitiveness of Australian enterprises by helping them to take advantage of advances in digital technologies such as analytics, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things. This, in turn, is benefiting their customers, employees and the communities in which they operate.

TCS is also deeply committed to investing in the Australian technology workforce of the future. So far more than 1,000 students have taken part in the TCS Go IT program that aims to inspire young Australians, particularly girls at secondary level, to consider careers in technology.

As one of India's largest companies and one with a significant global presence, TCS is partnering with DFAT to give university students a taste of work and life in India as part of the New Colombo Plan.

At the same time, TCS is contributing to the Commonwealth's science and technology agenda via a number of initiatives. TCS is a key participant in the Australian Government's Cyber Security Cooperative Research Centre and is building an innovation laboratory in Australia, which will operate as a collaborative space for TCS and its industry partners to utilise the company's vast network of expertise in innovation.

TCS is giving Australian companies access to leading technology platforms to support their growth and productivity. As one of India's largest companies, TCS acts as a bridgehead to Australian research and technology businesses seeking to take advantage of opportunities in one of the world's fastest-growing economies. TCS's ongoing investment in Australian ideas, innovation and people is strengthening both countries' competitive edge in global markets.

Figure 21: Indian Capex in Australia by Sector (January 2003 – September 2017)

Source: Fdiintelligence.com. 2018 [cited 3 May 2018]. Available from: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/

Portfolio Investment

India's capital markets

Twenty-five years of gradual reform effort has added depth and flexibility to India's capital markets. Commercial bank cash reserve and asset requirements are lower, India's administered interest rate structure has been eliminated, the exchange rate became determined by the market, prudential banking reforms were introduced, private sector commercial banking licenses were provided, and a contractual savings system was developed. As a result, and despite the NPAs, large parts of India's financial sector are profitable, efficient and growing rapidly.

India's equity market is well developed. At the end of 2017, the Bombay Stock Exchange was the world's 10th largest by market capitalisation, with USD2 trillion in assets. It aims to have 250 million investors by 2035 (up from more than 25 million today) and a market capitalisation of over USD15 trillion.24 India's government bond market is large and highly liquid and India has a large private mutual funds industry, with around USD200 billion under management, and good growth prospects.

However, further hard reforms are needed to increase the availability of financing and lower India's cost of capital. Calls to further privatise India's banking sector in a bid to increase its profitability are compelling. Public sector banks hold approximately 70 per cent of total banking assets but account for only 43 per cent of banking sector profits.23 Pension sector privatisation and privatising India's public-sector dominated insurance industry would add further depth to India's domestic debt and equity markets.

Foreign portfolio investment

India has allowed foreign institutional investment in Indian shares and debentures since 1992. This has been transformative, with FPI stocks growing at a compound average rate of 13.6 per cent over the past 20 years (Figure 22).

FPI reforms over the past decade have also been impressive and are ongoing. Foreign investors are now able to invest directly in India's listed companies and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has recently relaxed approval norms for registered foreign portfolio investors in India.

The number of registered investors has grown rapidly as a result. According to SEBI data, more than 1,000 new investors were registered with the regulator in the first six months of the 2017–18 financial year alone, bringing the total number to just over 8,800.

Figure 22: Portfolio Investment, Net Foreign Stocks

Source: Reserve Bank of India (IN). International Investment Position: 1997–2017. New Delhi IN: Government of India; 2017.

Reforms could go further, particularly with regards to facilitating FPI in the corporate bond market. Foreign portfolio investors are prevented from investing more than USD51 billion in Indian corporate debt by a hard FPI investment cap (which has been fully taken up).viii

Tentative steps have been taken to mitigate the cap's impact. In 2017, Masala bonds (rupee-denominated overseas bonds) were removed from India's FPI corporate debt investment cap, making an additional USD6.79 billion in domestic corporate debt available to offshore investors.24

In 2016, requirements for foreign portfolio investors to purchase bonds through Indian brokers were also relaxed, reducing transaction costs. Given the need to boost domestic investment and facilitate hedging, a gradual further expansion of FPI caps would seem a logical policy outcome.

Outward Indian portfolio investment

Outward Indian portfolio investment has much scope to grow from a very low base. Again, regulatory reform will be key. Currently, Indian individuals are prohibited from investing more than USD250,000 per annum in overseas instruments such as mutual funds, or private equity vehicles.25 Indian funds with greater than 35 per cent exposure to international assets are subject to a higher rate of tax on capital gains. As a result, while there are more than 40 Indian funds with exposure to international markets, no major fund has more than one-third of total assets in foreign positions (as of 31 May 2017).

Trends in Australian Indian portfolio investment

Stocks of Australian portfolio investment in India have increased from a very low base to $6.7 billion in 2016 (Figure 23). Over time, India's growing economic importance should become more attractive to Australian investors, with a rising share of funds likely to seek out Indian investment opportunities. India may be particularly appealing as a natural hedge to Australian funds seeking regional or global portfolio diversification.

Figure 23: Australian Portfolio Investment in India

Source: 1) Australian Bureau of Statistics (AU). ABS cat. no. 53520.0; Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2018. 2) Treasury (AU). Unpublished internal calculations; Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2018.

Note: 2006 are estimated figures

What could affect Australia's future investment relationship with India?

Greater familiarity of opportunities and limits

One of Australia's advantages as a potential source of investment in India is the scale of its managed funds industry. On the one hand, having $2.7 trillion in funds under management excites Indian interest.28 On the other, it stimulates unrealistic expectations that a significant portion of funds could reasonably be invested in India, including in greenfield Indian infrastructure opportunities.

Greater familiarisation between Australian investment professionals and Indian interlocutors can bridge expectation gaps, including on time horizons for investment decisions by Australian funds – in some instances these are comparatively short term unlike defined benefit funds in other countries, such as Canada. Small Australian funds are unlikely to establish commercial presence in India due to cost considerations, or invest in high-risk, long term, projects which the Indian Government is most keen to promote. Rather, small Australian funds are more likely to operate on a fund the fund type basis.

While Australian infrastructure funds are collectively large with $220 billion under management,26 the relatively fragmented sector generally seeks comparatively de-risked brownfield opportunities.

Australian delegations visiting India play an important role in enhancing knowledge about Australia's foreign investment settings and regulatory environment, particularly outside Delhi.

Bridging the expectations gap between the Indian Government and Australian investors will contribute to a sustainable, long term portfolio investment relationship.

Investment vehicles

Ultimately, facilitating Australian fund flows will require developing more, and more appropriate, investment vehicles – either by the Indian Government or by investment banksix.

India has developed several promising vehicles such as the Railway Infrastructure Development Fund in 2017 and India's quasi-sovereign National Investment and Infrastructure Fund in 2015 [see Chapter 9: Infrastructure Sector].

Private sector-focused multilateral development institutions such as the World Bank Group's International Finance Corporation (IFC) have an established presence in emerging markets such as India and a clear mandate for attracting international investment. They can be a valuable ally in pursuing policy and regulatory reform, developing context-appropriate investment vehicles, and attracting Australian investment funds.

There is a role for the Australian Government in promoting the benefits of, and need for, such funds. Intermediary institutions such as the IFC can be an avenue to cement closer bilateral investment ties, and help Australian industry navigate the challenging Indian market.

Negotiations and options for investment protection

India unilaterally terminated its BITs in 2017. These provided various legal protections for foreign investors in India (and Indian investors in other countries), including through ISDS mechanisms. The Australia-India BIT, which entered into force in 2000, will continue to apply for 15 years to investments made on or before its termination date of 22 March 2017.

India's actions send mixed messages. On the one hand, the Indian Government is seeking to increase foreign investment to support initiatives like Make in India. On the other hand, the new Model BIT weakens protection both for foreign investors in India and for new outward investment from India. This is consistent with the Indian Government's broader instincts to intervene and control the market.

Prospects for agreeing a high quality BIT with mutually acceptable terms appear low in the short to medium term. However, conclusion of a successful trade agreement negotiation, such as Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), could secure improved legal protections for investors in India.

Ongoing reform in India

The attractiveness of India as an investment destination rests with its reform and should be substantial over the period out to 2035: the relevant metric is not what Indian policy makers can achieve in a handful of years, but what they might achieve over a generation.

The likelihood of sustained reform does not mean that India will become an 'easy' market for investment, or trade, any time soon. But if India steadily becomes a much bigger market in sectors where Australia has a competitive advantage, how long can Australian business afford to stay under-weight in the investment elements of the relationship?

The approach of Australian business and the Australian Government

On the issue of successful investment at the company level, the message from business surveys is clear. First, be cautious, patient and invest for the long term. India moves at its own pace. It provides real opportunities for traders and investors, but also presents them with multiple risks that may be hard to define and harder to quantify. Investing in India is not a science and should not be hurried.

Second, prepare meticulously. Investors must develop an in-depth knowledge of the local market and reinforce that knowledge by choosing a trusted local partner to provide local context and access to networks. Focus on sectors or sub-sectors that are priorities for India's governments – like agricultural technology, resources management, infrastructure, and upskilling. And focus too on high performing states and where, ideally, Australian companies have already made inroads.

The Australian Government could play a valuable role by reinforcing these messages and addressing information gaps, including by highlighting the practical results of Indian reform. Introducing interested parties to private-sector focused multilateral institutions such as the IFC can help Australian industry manage risk and expand market access at the central and state level in India.

The approach adopted for India should be part of an overall Australian Government strategy for outward investment that is prominent and well-resourced – as should be the strategy for inward investment. Austrade logically would have policy responsibility for both inwards and outwards investment.

An ambitious target for investment

While the government has no role in directing the allocation of investments, even by its sovereign wealth funds, the Australian Government should support the facilitation of outbound investment where these projects support trade and increase the competitiveness of the Australian firm. This report sets the target of India becoming the third largest destination in Asia for Australian outward investment by 2035. Were this achieved it would represent a transformational increase of economic integration.

Given the current stock of investment, this is ambitious. Currently Japan, China, Singapore, Hong Kong and the Republic of Korea are larger destinations for Australian investment in Asia and flows there will of course continue to grow. A simple analysis indicates that investment to India would need to grow by at least 13 per cent per annumx to achieve this target.

Moreover, to generate the critical mass of on the ground presence needed to build trust, establish networks and enhance business to business ties, Australia will need a greater proportion of future investment to India in the form of FDI.

As laid out in this chapter, there are multiple risks and challenges with reaching this target. However, that it is even conceivable points to the potential and scale of the India story over the next 20 years.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- 1.Bridge knowledge and expectation gaps in India and with the Australian business community

- 1.1The Australian Government should seek to address information gaps in the Australian business community. Given the Australian Government has no role in private sector investment decisions, this recommendation is about facilitating adequate information to optimise decision making. It can do this by:

- highlighting the practical results of Indian reform to the Australian business community

- detailing any common threads underpinning successful market entry, including the need for: a well-resourced and patient approach to investment; meticulous due diligence and triangulation of accounting data inputs; and a trusted local partner to provide local context and access to networks.

- 1.2The Australian Government should seek to bridge the expectations gap between the Indian Government (which views the large Australian managed funds sector as potential green-field infrastructure funding source) and Australian fund managers (who are typically interested in brown field, income-generating and low-risk opportunities).

- 1.3The Australian Government should support familiarisation visits to help Australian investors understand opportunities in India

- there is merit in the Australian Government regularly bringing out a small group of Australian superannuation funds representatives and institutional investors for a targeted program of meetings in Mumbai, New Delhi and south India

- this will provide an opportunity for Australian investors to hear first-hand experiences from other foreign investors and also to sit down with Indian Government officials to build mutual understanding about realistic opportunities in India

- in the first instance, delegations should be comprised of fund managers – ministerial engagement should be considered once there is a clear appetite for investment into India

- premature ministerial attendance could raise Indian expectations of the quantum and timing of Australian investment, which industry may not be able to fulfil.

- 1.1The Australian Government should seek to address information gaps in the Australian business community. Given the Australian Government has no role in private sector investment decisions, this recommendation is about facilitating adequate information to optimise decision making. It can do this by:

- 2.Build institutional ties

- 2.1Australia should build closer institutional ties with Indian agencies responsible for investment policy and regulation. Australia has a good story to tell on financial market reform and has internationally recognised institutions with proven records of achievement in implementing reforms which support investment.

- 2.2Share Australian Governments' asset recycling and privatisation experiences. This represents a practical way to build capacity and potentially open up opportunities for Australian funds seeking infrastructure investment opportunities

- regular policy dialogues between Treasury and Ministry of Finance and NITI Aayog present one opportunity for this to be done at an officials' level, including through the 'GST working group'.

- 3.Strengthen Austrade's mandate for investment promotion

- 3.1Austrade should give greater priority to inwards investment attraction from India.

- 3.2Austrade should strengthen efforts to provide facilitation services for direct investment to India where these projects support Australian trade and increase the competitiveness of the Australian firm, particularly among SMEs.

- 3.3Australia should also seek to strengthen its presence in India to support corporate issue resolution and approvals-related interaction between Australian firms and Indian Government departments at the state and central levels

- this could be supported by exchanges and secondments with Indian Ministries which control approvals or incentives relevant to Australian investors, as well as between Austrade and Invest India.

- 4.Joint research projects on bilateral investment opportunities

- 4.1The Australian Government, through Austrade or DFAT, should commission short research projects to better understand the experience and potential of Australian institutional investors in India or of Indian investors in Australia.

- 4.2A separate report could be commissioned to compare risk-adjusted returns across sectors in India and Australia, following on from the PricewaterhouseCoopers/Asialink Match Fit report which noted that Australian businesses underestimate the risk of the business climate in Australia and overestimate the risk in Asia.

- 5.Pursue greater investment protection

With the Australia-India BIT now terminated unilaterally by India, a successor arrangement covering investor protection and investment facilitation should be a high priority

- given significant concerns about the level of protection that India's model BIT would provide, the prospects of an Australia-India investment treaty are currently very limited

- concluding a workable investment chapter in the current RCEP negotiations is a more realistic alternative.

- viii99.8 per cent was utilised as of 24 November 2017 according to India's FPI Monitory database.

- ixVehicles which significantly pool assets and minimize idiosyncratic project/firm-specific risk are likely to appeal to a broader swag of Australian investors with relatively limited market knowledge and no appetite or ability to establish in India.

- xThis is based on basic regression analysis to estimate projected growth rates for Australia's investment with India and other markets out to 2035. It assumes investment to Singapore, Hong Kong and the Republic of Korea will grow at an average of 4.5, 3.5 and 1.9 per cent respectively. This is provides a simple indication of the order of magnitude between India and other major markets. Given the growth in total FDI and FPI stocks in India over the last 20 years (19 and 13.6 per cent respectively), it is possible to imagine total Australian investment in India growing at 13 per cent out to 2035.