Summary

- Out to 2035, India's increasing urbanisation, rising household incomes and industrial activity will drive demand for greater volumes of key Australian resource commodities.

- Australian resource exports to India, particularly metallurgical coal, but also copper and gold, will continue to make up the bulk of our merchandise trade.

- Our mineral resources relationship will continue to be dominated by exports, rather than outbound Australian investment. The Government of India is very active in this sector and the weight of state-owned enterprises, layering of central and state regulations, and poor contract enforcement issues, complicate foreign participation on the ground.

- As part of spreading risk, we should continue to seek Indian investment in Australian resource assets including through sustained messaging on Australian investment settings and business culture. This will need to be managed in light of the problematic experience of Indian companies investing in the coal sector.

- India is one of the most important future markets for Australian METS companies. As India grows and seeks to modernise its mining sector, METS will increase across the board. Australian METS companies have a competitive edge, particularly in the coal value chain and beneficiation.

1.0 The macro story

Key judgement

India's projected growth will keep resources trade high in our bilateral economic relationship. Demand for Australian resources will be strongest where domestic Indian reserves are limited, including in metallurgical coal, copper, and gold. India's demand for both metallurgical coal and copper is forecast to grow at around 5 per cent per year to 2035; over 90 per cent of this is expected to be met by imports. India will continue prioritising price over quality and product life-cycle costs, creating some unpredictability for resource commodity exports to India. As a result, the extent of our market share in these key commodities will depend primarily on the competitiveness of our exports against others.

1.1 The scale and key structural drivers of the sector

Resources are, and will remain, a significant component of the Australia India economic relationship

- commodities at the heart of this include metallurgical coal, copper, gold and, to a lesser extent, iron ore [see Section 1.2 for commodity breakdowns]

- with demand for minerals and metals driven by India's economic development, increasing urbanisation, rising household incomes and industrial activity, market conditions for Australian resource exports to 2035 look promising

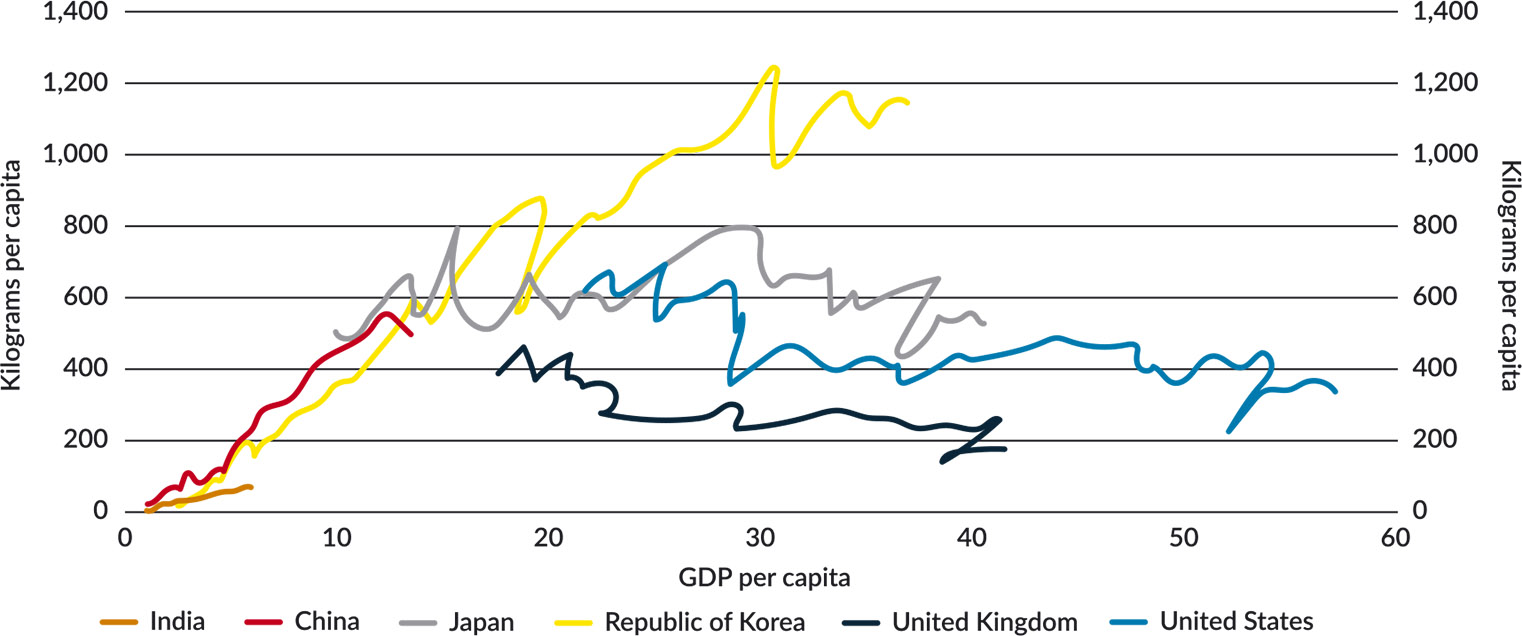

- India's low level of steel intensity (which is less than one-third of the world average, see Figure 2438) is indicative of the catch-up growth in resource-use India is likely to experience as its economy grows out to 2035.

Figure 24: Steel usage intensity 1950 to 2017: high intensity path countries and India

Source: Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (AU). Resources and Energy Quarterly September 2017 [Internet]. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2017.

India has significant resource endowments of its own and the Government of India needs to – and is seeking to – modernise its mining sector and improve efficiency

- India has a large reserve base of minerals and metals (such as iron ore, zinc, lead, bauxite, and thermal coal)

- it is the second largest global producer of thermal coal and fourth largest producer of iron ore39

- but it has few reserves of metallurgical coal, gold and copper

- India's mining sector is underdeveloped

- the contribution of the mining sector to India's GDP has been stagnant at around 2.5 per cent over the last decade

- in the period 2004–2014, the Indian mining sector grew at an average of 7.3 per cent per annum compared to 22 per cent in China40

- India's spend on exploration projects is 0.3 per cent of the global spend (compared to 19 per cent for Canada and 12 per cent for Australia)40

- given the scale and growth of India's resources and mining sector, and the need for better productivity, demand for METS will increase across the board

- fuelled by an increasing proportion of underground mines in India and growing concerns for environmental and safety issues

- accordingly, India is one of the most important future markets for Australian METS companies, along with Indonesia and the United States

- Australian equipment and services that deliver more productive, cleaner, safer mining and resources extraction are particularly of interest to India.

Australia's competitive advantage

As the world's largest exporter of iron ore and metallurgical coal, the sixth-largest exporter of gold, and the third-largest exporter of copper, Australia has a sophisticated and export-focused industry with established channels into India

- as illustrated in Figure 25, metallurgical coal, gold and copper make up over half of all Australian goods and services exports to India, providing the baseload of our trading relationship

- Australia provides 80 per cent of India's metallurgical coal imports.38

Australia is a recognised global leader in METS.

Australian METS companies have a competitive edge in the following areas:

- sustainable environmental management and safety experience (mine closures, mine site rehabilitation, groundwater conservation, mine safety)

- advanced technology and systems (including in underground mining and to raise productivity and product quality)

- advanced mineral exploration (large parts of India have no, or very little, data on resources potential)

- initiatives to manage structural change in the mining sector (for example through technical upskilling and increasing awareness of environmental externalities).

Australia also has experience in managing the relationship between mining companies and communities including traditional landowners.

Figure 25: Australia's goods and services exports to India 2016–17 ($ million)

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (AU). Services Trade Access Requirements Database. Canberra AU: The Commonwealth of Australia; 2017.

1.2 How the sector will likely evolve out to 2035

Global trends will re-shape the Indian and Australian mining and resources sectors

Current trends41 indicate that out to 2035 we will see:

- the application of more advanced mining and processing techniques, including new digital technologies, data analytics and automation to make extraction and distribution more efficient

- growing interest in corporate accountability will see greater public scrutiny of environmental and sustainability considerations

- increasing rates of urbanisation and infrastructure development in emerging economies will lead to greater global demand for mineral resources

- there will be a greater global emphasis on expertise in services and technologies to exploit mineral reserves efficiently

- the need for innovation will increase in the face of declines in ore grades and rates of discovery relative to rates of depletion.

India has ambitions to improve its resources and mining sector

India is seeking to improve the utilisation of its mineral resources through 'scientific and sustainable mining practices and geo-scientific research and development' by40

- expanding its resource and reserve base through greater exploration and acquisition of strategic minerals

- reducing permit delays

- improving mine infrastructure, human capital and technology

- enforcing sustainable mining through regulatory changes.

Progress in any of these elements is likely to be incremental.

CASE STUDY: Tata BlueScope Steel: Two industrial giants make a successful match

For Australian steel producer BlueScope, forming a 50–50 joint venture with major Indian conglomerate Tata in 2005 has been a highly successful match. While it took a number of years for the business to become profitable, in the first half of fiscal 2018 Tata BlueScope Steel had underlying earnings of approximately $28 million, with revenue growing by 7 per cent.

In India, the Tata brand is ubiquitous, covering everything from salt to motor vehicles to steel. Tata was chosen as the joint venture partner due to its corporate values, local brand recognition, well-established distribution channels and secure sources of raw materials. As an Indian private sector conglomerate, Tata also understands how to work with government in India, where relationships are key.

BlueScope offered complementary skills and experience. It had long-established expertise in metal coating and painting technology, marketing skills and customers around the world for its pre-engineered building products.

The joint venture produces a range of steel products supplying well-known global brands such as COLORBOND® steel and LYSAGHT®, as well as local brands such as the flagship DURASHINE® steel. The principal market is India's building and construction sector. Economic activity and urbanisation in India has ensured strong local demand for its coated steel building products, as well as demand from across South Asia and around the world.

The business did face a number of challenges that required dedication and commitment from the partners to overcome.

The construction of a metal coating and painting plant ran into some difficulties with significant delays, but Tata Steel's local knowledge assisted with development approvals and local government relations to complete and commission the plant, which has since been operating successfully.

The joint venture took a number of years to become profitable and some parts of the business were underperforming and required restructuring. The joint venture partners worked together on a suitable revised business plan and to develop an appropriate approach to deal with the restructured assets.

Over the last few years, the joint venture business successfully refinanced term loans and exercised an option for early redemption of debentures. Both shareholders supported the joint venture in its dealings with lenders and regulatory authorities.

More than a decade later, Tata BlueScope Steel has six major manufacturing plants across India, employing 550 people, with revenue of around $400 million. Expansion of production facilities is on the cards.

Recent changes to sales tax, resulting in more uniform taxes across Indian states, has worked in the joint venture's favour.

Perseverance by BlueScope in India has been important. It took a long term view, and specialised in doing what it knew how to do best. Working with Tata, the right partner in India, has also been key to the joint venture's success.

Indian demand for key resources commodities out to 2035

India's demand for resource commodities will continue to grow. Of significance for Australia's areas of competitive strength, India is likely to remain import reliant for metallurgical coal, gold, and copper out to 2035.

Metallurgical coal

India's National Steel Policy 2017 sets a highly aspirational steel consumption target of 255 million tonnes per annum by 2030 (India's crude steel production is currently around 100 million tonnes). This would require around 196.4 million tonnes of metallurgical coal per annum – an expected growth in demand of 4–5 per cent per annum from 2016 to 2030.

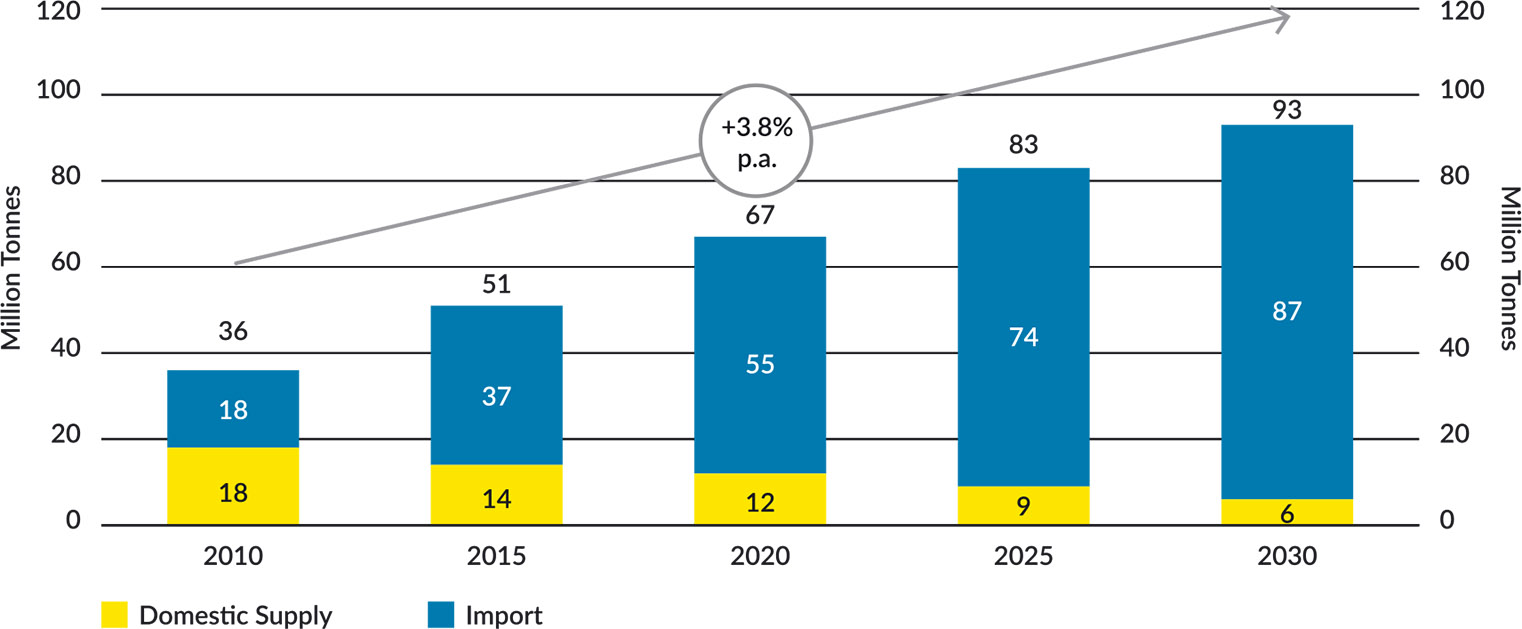

By 2030, over 90 per cent of India's metallurgical coal demand is expected to be met by imports (see Figure 26)

- domestic reserves are limited, poor quality and extraction is increasingly difficult due to dwindling shallow seams, increasing protests against new open cut mines and low productivity for underground mines

- domestic production is expected to continue declining; by 2030 it will have fallen by half to 6–8 million tonnes.

While India is looking to diversify its import sources, Australia will remain well-positioned to meet India's continued strong import demand, given the high quality of our metallurgical coal and that we are India's top supplier by a considerable margin42

- Australia dominates India's metallurgical coal imports due to its low landed cost

- our total exports should continue to grow, even if our market share slips.

Figure 26: Indian coal demand

Source: Work commissioned by the India Economic Strategy Secretariat to support this report.

Iron Ore

Although India has about 30 billion tonnes of iron ore reserves and was a net exporter of iron ore as recently as 2012, India has recently become a net importer12

- domestic Indian production is limited due to challenges in product quality and accessing land and capital; production is also affected by uncertainty around government regulations

- for example, concerns around environmental damage led to temporary bans on several mines in Goa and Karnataka.

In the short to medium term, these challenges will mean Indian domestic production is unlikely to meet demand and opportunities will continue for Australian iron ore exporters

- the prospect for growth in imports is reinforced by limitations in India's rail and port infrastructure which make it easier to supply steel mills on the east coast with imports, rather than with iron ore transported from domestic mines.

In the long term, Indian iron ore import growth is uncertain

- technical developments in India's steel industry could see sustained demand for imported iron ore with a lower impurities content, like Australia's

- but Indian domestic production could increase from investments in beneficiation capacity, making low-grade iron ore suitable for steelmaking.

Copper

Indian demand for copper is being driven by urbanisation, increased rollout of electrical transmission networks, and the manufacturing sector.

India has limited copper ore reserves, constituting just 2 per cent globally, and imports around 95 per cent of its copper requirements as concentrates.12

Supported by India's growing refining capacity, India's import reliance on copper will likely remain above 90 per cent as demand continues to grow at a steady pace. Future demand growth is expected to be in the range of 5–6 per cent per annum.12

Growing demand presents opportunity for Australia to increase its 11 per cent market share, if it can maintain landed cost parity with competitors.

Gold

India is one of the world's largest consumers of gold, with almost 80 per cent of demand coming from end-use in jewellery and as household investments

- India has the world's largest private gold holdings

- consumer preferences for gold are culturally entrenched and unlikely to change meaningfully out to 2035.

CASE STUDY: Geoscience Australia: contributing to a more advanced Indian mining industry

Hundreds of millions of years ago, Australia and India were both part of the ancient super-continent Gondwana. Today both nations share geological similarities and Australian geoscientists can apply their knowledge and experience in the Indian context.

As India becomes more urbanised, and demand for mineral resources grows, understanding regional geology, and being able to predict the potential for undiscovered mineral deposits, is becoming increasingly important.

India has an ambitious vision to develop its vast mineral resources, and to do so needs a modern exploration and mining sector. Geoscience Australia is using its internationally recognised technical expertise to assist the Geological Survey of India in becoming a world-class geoscience organisation.

Through a Memorandum of Understanding, Geoscience Australia is building the capacity and technological capability of the Geological Survey of India to assess the potential for minerals deep underground. It is holding ‘train the trainer' workshops in India, inspecting equipment and facilities, and seconding Indian officers to work inside Geoscience Australia.

Together, the agencies are developing a ten-year vision for the Geological Survey of India.

Collaboration has mutual benefits for Australia and India. Through its engagement with Geoscience Australia, India is also set to draw on the expertise of Australian universities, Australian geoscience contractors, and the mining equipment, technology and services sector more broadly.

India has scant domestic gold reserves to meet this demand. Imports are either in refined or doré (partially refined) form. Doré imports have grown as the Indian Government has sought to incentivise domestic refining while imposing import restrictions on bullion imports.

Australian gold exports are primarily in bullion and Australia competes with South Africa as the primary producer of gold exports to India, with Swiss traders and to a lesser extent the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom as the largest exporters

- internationally, bullion is often traded through the United Kingdom and the pathway for Australian gold to India can be through the London Bullion Market, or other markets, which affects our export figures.

Australian exporters may be affected by Indian regulatory settings including

- efforts to monetise domestic gold holdings to recycle it back into the Indian gold sector and lessen the need for imports

- efforts to formalise gold transactions and clamp down on gold smuggling

- the establishment of physical gold exchanges, which would increase transparency in the market and standardise prices.

The value of Australia's gold exports to India in recent years is set to keep fluctuating with these domestic policy settings as well as international gold prices.

Critical Metals and Rare Earth Elements

The increasing adoption and use of new technologies, including environmental technologies, will mean India will require commodities such as critical metals and rare earth elements, of which Australia has reserves.

India is one of the 10 or so countries that also has its own rare earth reserves and active mining projects. The Indian Government is trying to promote rare earth mineral exploration and production from a very low base. If India looks to increase its rare earth refining capabilities out to 2035, there may be the opportunity for partnership with Australia.

2.0 Opportunities for partnership

Key judgement

Out to 2035, there are good growth opportunities in the value and volume of our metallurgical coal, copper, and gold exports to India. Attracting Indian investment into the Australian resource sector can bring in capital and create jobs. For India, vertically integrated investments into Australia can help smooth commodity price volatility. As India's exploration and extraction continues to grow, so too will opportunities for Australian METS companies. However, the well-trodden pathway for Australian METS companies to follow Australian resource majors into markets is unlikely to eventuate in the Indian market.

2.1 Export opportunities

COMMODITIES

Table 2 projects the demand, supply and import figures out to 2030 for key commodities.12

| Resources | Units | Indian Demand | Indian Domestic Supply | Indian Imports | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2030 | 2016 | 2030 | 2016 | 2030 | ||

| Metallurgical coal | Million tonnes | 52 | 90–100 | 15 | 6–8 | 87% | 90–95% |

| Iron ore | Million tonnes | 154 | 290–300 | 156 | 290–300 | 5% | 0–3% |

| Copper | Thousand tonnes | 511 | 1000–1200 | 26 | 70–100 | 95% | 91–94% |

| Gold | Tonnes | 735 | 1000–1100 | 1 | 2–3 | ~100% | ~100% |

Services exports – METS

Some 35 Australian METS companies are already active in India.

India's demand for METS will grow out to 2035, particularly in connection to those commodities for which India is prioritising greater domestic output, such as thermal coal where Coal India has big and sophisticated aspirations [see Chapter 7: Energy Sector]

- Australian METS companies are strong across the entire coal value chain

- Australia's underground coal mining, geomechanics, ventilation, and safety expertise is particularly relevant and well regarded by Coal India.

Beyond coal itself, there will be opportunities in advanced Indian mining projects for exporters of mining IT, planning software, safety, health and risk management technologies and methods, and training in all its forms

- partnering with Indian IT firms, with operations in Australia, such as Tata Consulting Services, Wipro and Infosys, might help Australian METS firms looking to enter the Indian market in the technology space.

The projected growth in India's METS sector offers Australian firms, a large number of which are SMEs, the opportunity to increase participation in Indian supply chains through research and development collaboration and joint ventures

- we will require new approaches to collaboration to succeed – a united Australian METS brand in India would be a useful starting point.

Although manufacturing products in India could help Australian products compete in the price-sensitive Indian market, any sort of large-scale METS manufacturing hub is unlikely, as Australia manufactures only certain niche products and little by way of automated equipment.

2.2 Collaborations

The METS sector in particular offers a number of collaborative opportunities as India's mining sector grows out to 2035.

Research and Development

At the peak of the resources cycle in 2012–13, Australian METS companies generated revenue of $90 billion globally and employed an estimated 386,000 people41

- post-boom, a particular challenge is the need for new sources of productivity at lower costs41

- in Australia's highly capital intensive mining and resources sector, this productivity will continue to be driven by innovation and new technology.

Collaboration between Australian and Indian mining technology research institutions can be the precursor to joint commercialisation and METS exports

- there are numerous areas of research interest to India where Australia can not only provide expertise, but could also result in cooperation including in carbon capture storage and utilisation, coal preparation upgrading and fugitive emissions from coal mining.

A number of Australian METS companies have an established local presence, or use a local partner, in India. This investment, while modest in overall dollar terms, has the potential to grow and create Australian company clusters

- to an extent, this is already taking place in Kolkata (West Bengal), a regional hub for METS and a gateway to the mineral-rich states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha.

Education and training

Collaboration on education and training could include Australian METS providers partnering with training organisations and offering industry-embedded courses and research degrees

- the Government of India and mining industry are interested in adopting suitable elements of Australia's safe, productive and efficient mining culture in India

- this could extend to introducing Australian best practice mining legislation and regulation.

Platforms for partnership

The Australia-India Mining Partnership at the Indian School of Mines at IIT Dhanbad (IIT-ISM) provides a platform for training, research and development engagement

- this has the potential to create a cluster for Australian engagement in the coal belt states of India and could be replicated across other institutions, and expanded beyond research and training to incorporate industry

- the existing framework includes a Centre of Excellence in Mining Technology and Training, memorandums of understanding between eight Australian institutions and IIT-ISM, a joint doctoral program with Curtin University, technology transfer (particularly in mine safety) and industry-funded research and development

- the Australian Government has also funded an Austrade partnership coordinator at IIT-ISM to facilitate activities between stakeholders

- further funding, particularly for the research and development component will be required to make the most of this platform.

2.3 Investment

Into Australia

A key focus should remain attracting Indian investment in the Australian minerals sector.

Australia's vast resources base requires foreign capital, technology and markets for further development.

Indian steel manufacturers could look to secure Australian metallurgical coal assets, considering the projected increases in Indian demand. Coal India has also expressed an interest in acquisitions in Australia.

India's investment experience in the Australian coal sector (both metallurgical and thermal [see Chapter 7: Energy Sector]) has been problematic. The absence to date of a high profile and profitable flagship investment could deter Indian investment interest. However, Indian investment into Australian resources projects would provide important returns for Indian companies in mining related skills.

Into India

Resources is one of the most challenging direct investment sectors in India for foreign participants with limited prospects of anything more than incremental change

- even the largest international companies have found it difficult to secure necessary clearances and permits across various central, state and local jurisdictions to undertake exploration or extraction

- land acquisition is difficult and needs reform, while approval timelines are slow and recourse to legal avenues lengthy

- there are few examples of successful foreign investments in India's resources sector although BlueScope Steel has persevered in partnership with the Tata Group and its Indian operations are now performing well.

3.0 Constraints and challenges

Key judgement

While making up the bulk of our merchandise exports, the government-dominated resources sector in India brings with it a range of regulatory barriers, which constrain commercial activity. Despite an apparently open FDI regime for resources, the costs associated with domestic regulatory compliance remain a hurdle to foreign investment. A lack of investment in exploration, and inadequate information about proven reserves, are also key issues impeding India's mining industry with India having explored only 10 per cent of its mineral resources to date. For METS especially, behind the border restrictions on licencing and permits inhibits the delivery of professional services into the Indian market. Corruption, poor contract enforcement, and uncertainty over land tenure adds to this complexity and cost. In terms of commodity exports, a key challenge for Australian firms is the increasing global competition from emerging economies where the cost of production is significantly lower.

3.1 The policy and regulatory environment

Constraints in the policy and regulatory environment within the mining and resources sector are unlikely to improve meaningfully out to 2035.

Tariffs on minerals and metals are among the lowest categories across the Indian schedule

- but India's customs tariff and fee system is complex and lacks transparency in determining net effective rates of other duties and charges

- there are multiple elements and rates are often adjusted at short notice.

Tariffs are higher for METS (often three to four times higher than for ores and concentrates) and are also accompanied by a host of other fees and border charges

- as well as restrictions on skilled worker access to India, particularly for engineering and construction services.

Due to the unpredictability of business conditions, India does not attract FDI commensurate with its importance as a producer of minerals and energy or its potential to increase output substantially

- the Minerals Council of Australia assesses 'without more clarity and predictability, the easiest option for perhaps the majority of foreign mining and METS companies is to trade with India and stay away from the bureaucratic complexity of operating businesses there'.

The list of regulatory barriers to investment and foreign participation in India's resources sector is long. Some of these challenges are applicable to other sectors of the economy, and include:

- fragmented Ministerial responsibility across the sector

- difficulty in transitioning from exploration to exploitation disincentivises foreign investment and participation

- greater security of minerals leases would make the regulatory environment more predictable, but is not guaranteed

- the current tendering process for mining projects prioritises price over quality, efficiency or life-cycle costs

- this negatively affects Australian companies, which have a higher cost of production and higher quality services and exports

- land acquisition remains a persistent constraint on resources productivity

- State Government-led land acquisition reforms could improve the ease of doing business in this sector.

CASE STUDY: SIMTARS: Queensland mine safety expertise rewarded for building relationships

Mining plays a major role in the Indian economy, and the Indian Government has ambitious plans for growth. But India needs new technology and modern mine safety and health systems to develop its reserves, and power its economy.

Queensland's Safety in Mines, Testing and Research Station (SIMTARS) offers this expertise. It has taken a long term view, starting in India in 1998 with small training projects delivered to India's Directorate General of Mines Safety. It has gradually built relationships since then.

SIMTARS is now seeing results. India's 2017 national mine safety law is based on Queensland legislation. SIMTARS has a contract with the Indian School of Mines to supply and deliver a virtual reality theatre and spontaneous combustion and explosion laboratory. It also has major contracts with Coal India and its associated subsidiary Singarini, to deliver training and a real time underground gas monitoring solution.

SIMTARS has built relationships by making regular visits to India every year, attending conferences, giving keynote speeches, providing specialist advice and delivering training and gas monitoring solutions.

SIMTARS has made the most of its institutional connections. Working through the Indian School of Mines it has been able to connect with some of India's best researchers and gain access to those making purchasing decisions.

Government to government frameworks have been important for SIMTARS' initial engagement in India because Coal India, Singareni and SAIL are all state owned enterprises. However SIMTARS also works with private sector groups in Australia and has introduced them to the Indian market. It is also working with Indian private sector mining entities.

Ultimately, the Australian mining equipment, technology and services sector as a whole stands to benefit from the work of SIMTARS which demonstrates the value of international technology and expertise to India's efforts to develop a more advanced local mining sector. SIMTARS is one of many Australian groups from this sector working in India.

3.2 Skills infrastructure and other constraints

The structure of India's mining sector

Mining is concentrated amongst a few large public sector companies including Coal India Limited, Singareni Collieries Company Limited, Steel Authority of India Limited and Hindustan Copper Limited

- though inefficient, it will be challenging for India to privatise these assets due to the political risk of job losses

- while the dominance of these companies complicates foreign investment and participation India's February 2018 announcement of auctioning coal blocks for commercial mining opens the sector to private investment and erodes the monopoly of Coal India.

Over the last decade, the private sector has played an increasingly active role in the mining sector and large Indian corporations including Tata Steel, Vedanta, Aditya Birla and Jindal are making investments in mining and related technology.

India also has some smaller, disparate companies operating at the margins of India's regulatory environment. In general, this third group are less reliable partners for investors or suppliers.

Diversification

India's aims to diversify supply, along with its natural preference for import substitution, could see it look to reduce Australia's dominant market share in metallurgical coal.

METS price point

The price-sensitivity of the Indian market makes it difficult for foreign METS companies – who could offer cutting-edge technology and services – to compete with domestic players.

The profile of the Australian METS sector

Many Australian METS operators are SMEs and may not have the resources to undertake loss leader strategies while establishing themselves in India.

Competition

In the METS sector competition will continue from North America and Europe, while India's domestic METS sector will grow out to 2035.

India's business environment

While improving, contracts are often re-interpreted, leading to delays in payment or in granting licenses [see Chapter 15: Understanding the Business Environment].

Corruption

Independent reports have identified metals and mining to be some of the most vulnerable sectors for corruption in India43

- there is potential for automation to reduce opportunities for corruption, including in permit and license allocation, and some progress is being made in this respect.

4.0 Where to focus

West Bengal and the eastern states of India (Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Bihar and Odisha) are home to the majority of India's resource deposits and mining activity. This critical mass of Indian and Australian interest makes these eastern states natural targets for increased political investment in support of our long term export and investment relationship with India.

4.1 Key States

West Bengal

A regional hub for engagement on mining and METS, including as the gateway to the mineral-rich states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha, West Bengal will likely remain the most significant METS market for Australian companies in India.

The state's capital Kolkata is re-emerging as a growth centre

- Coal India, the world's largest coal company, is headquartered in Kolkata

- the Australian Government (Austrade) has maintained a presence in Kolkata for over 15 years, as have more than a dozen Australian METS businesses.

Jharkhand

Around one-quarter of India's total steel production comes from Jharkhand. With the proposed expansion of a number of integrated steel plants, Jharkhand is a steel hub of India.

The state is the sole Indian producer of coking coal, uranium and pyrite, and ranks first in the production of mica, kyanite and copper.

Investment: Jharkhand was ranked fifth as an FDI destination in India and seventh in Ease of Doing Business in 2016.

Australia's engagement with IIT-ISM is based in Jharkhand.

Odisha

Odisha accounted for 21.6 per cent of India's coal production in 2015–16, and the state ranks first in India in the production of chromite, manganese, iron ore and bauxite.

The state accounts for a third of India's iron ore reserves, a quarter of coal reserves, half of bauxite reserves, and almost all chromite and nickel reserves.

Odisha has around 50 per cent of India's aluminium smelting capacity and around 20 per cent of India's steelmaking capacity.

A number of Australian METS suppliers are based or working in Odisha.

Chhattisgarh

Resource-rich Chhattisgarh produces 27 per cent of India's iron and steel, 20 per cent of iron ore and 15 per cent of aluminium, presenting opportunities in METS.

Some of the best quality iron ore deposits in the world are located in the south of Chhattisgarh.

The state is also endowed with considerable reserves of bauxite, limestone and quartzite, and is the only state in India that produces tin concentrates.

Andhra Pradesh

There is also mining activity in south India, focussed around Andhra Pradesh

- world's largest deposit of baryte

- India's largest bauxite deposit, major ilmenite deposits, and largest off shore gas field

- Australian mining and extractives companies already have a presence in Andhra Pradesh.

CASE STUDY: CSIRO: Working to improve safety and productivity of Indian coal mines

India has ambitious plans to double domestic coal production by 2020. India has the fourth largest deposits of thermal coal in the world and is looking to Australia to provide mining technology and expertise.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the Australian Government's scientific research agency, is helping meet that demand, working with Singareni, one of India's state owned coal mining companies, in the southern Indian state of Telangana.

Underground mining in both countries uses longwall mining techniques and mechanisation to increase safety and make production more efficient.

The CSIRO and Singareni signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2006 to work on geomechanics and other research related to coal mining. This has led to collaboration on three major projects, worth $7.3 million.

At Singareni, high capacity longwall was introduced in their Adriyala mine with technical assistance from the CSIRO.

The collaboration has paved the way for advanced longwall mining technology to be introduced in more Indian mines. It is also set to improve safety and productivity as India strives to meet its energy needs.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Australia can continue to position itself as a trusted bilateral partner and a strong, reliable supplier of resource commodities and METS services. Government should look to provide greater support to Australian METS providers as they seek to create opportunities in the market. These efforts will be reinforced by continued government to government and industry engagement in India, including through upgrading the Australian Government's presence in and around India's resources hub of Kolkata. Our major resources play in India will remain export-based.

- 25.Leverage our status as a key supplier of resource commodities to support ongoing advocacy for improvements to the business environment

Our standing as a major resource commodities trading partner with India, and a country that India looks to as a leader on mine management, gives us currency within the Indian system. We should use this to build the Australian brand and further entrench engagement.

- 25.1Strengthen regular Ministerial-level engagement, including through the Australia India Energy Dialogue

- given the prevalence of state-owned enterprises in the sector, it is important to keep Australia among the forefront of the Indian Government's partners in the sector, relative to our competitors

- Australia should commit to this Dialogue as the mechanism to advance a resources policy agenda, address regulatory barriers, and as a platform to bring together industry and government stakeholders to discuss areas of mutual interest

- under the Dialogue, support the Australia-India Coal and Mines Joint Working Group

- focusing on policy frameworks and cooperation to support our METS and commodity exporting sectors

- incorporating industry and academia participation.

- 25.2Consider funding Geoscience Australia to strengthen its existing collaboration with the Geological Survey of India.

- 25.3Provide targeted funding to joint activities identified under the above frameworks, drawn from government and business, to give us a basis for further collaboration

- explore options to establish a joint fund between Australia and India, with co-investment from industry, similar to a resources sector AISRF

- draw on Australian development assistance to establish a mechanism for Australian METS companies to provide, on a commercial basis and protecting IP, research and development, technology and expertise to regional partners, with a priority placed on developing India's mining sector and METS standards

- such a fund could support practical activities between Geoscience Australia and Geological Survey of India.

- 25.4Explore options to work with India, and potentially a third country such as Japan, on the development of India's rare earth minerals and critical metals refining capacity.

- 25.1Strengthen regular Ministerial-level engagement, including through the Australia India Energy Dialogue

- 26.Expand support mechanisms for Australian business in METS

- 26.1Elevate branding of the Australian METS sector in India

- supporting a stronger national presence at trade fairs such as the International Mining and Machinery Exhibition

- with a coordinated communications and marketing strategy

- these efforts should be funded by industry, with Australian Government facilitation support.

- 26.2Explore options to set up an Australian industrial cluster at a demonstration mine in India showcasing Australian practices and leveraging the site for training

- for open cut and underground technology

- as a collaboration between government, industry and peak bodies

- would need Indian Government support to manage regulatory and tendering challenges

- these efforts should be funded by industry, with Australian Government facilitation support.

- 26.3Facilitate study tours for Indian mining executives to visit Australian mine sites

- to allow participants to observe technology solutions and understand management issues such as contract and contractor management

- these could be aligned with the dates of relevant Australian conferences and incorporate meetings with key Australian equipment and service providers.

- 26.1Elevate branding of the Australian METS sector in India

- 27.Support the knowledge partnership in resources and mining

- 27.1Increase financial and political support for the Australia-India Mining Partnership at the IIT-ISM to ensure it continues to grow out to 2035

- The partnership with the IIT-ISM should be used to showcase Australian expertise.

- The framework for engagement under this partnership is established. Modest funding of activities are essential for it to deliver outcomes in the short/medium term. Support could be directed to:

- executive training programs, with a focus on Australian standards and systems and advanced technology applications

- joint research projects on extractive and refining technologies

- facilitating student and faculty exchange between the IIT-ISM and Australian institutions

- promoting further linkages between Australian industry and the IIT-ISM in the fields of clean coal and mine safety

- making the Austrade-managed Business Development Manager embedded in the IIT-ISM a permanent role in addition to the Austrade presence in Kolkata.

- Such activities could build further institutional and branding support for Australian universities to develop and deliver management training courses and study tours in partnership with the IIT-ISM.

- The Australian Government should develop a communications and marketing strategy for the partnership at IIT-ISM.

- 27.2Explore options for capacity building programs

- with Indian officials using our mine safety and environmental standards

- explore options to provide short course training for Indian regulators to familiarise them with new technologies and enable faster approval processes.

- 27.3Support pathways for exchanges of post-doctoral employees and industry-embedded PhDs in both countries

- using the networks of Australian industry bodies such as METS Ignited, Austmine and the Minerals Council of Australia.

- 27.1Increase financial and political support for the Australia-India Mining Partnership at the IIT-ISM to ensure it continues to grow out to 2035

- 28.Promote Indian investment into the Australian resources and mining sector

- 28.1Continue to advocate (through high-level visits, trade missions and Austrade) for investment opportunities in Australia

- including targeting Indian investment in the resources sector to our Northern Australia development initiative.

- 28.2Ensure regulatory settings that are predictable and attractive to foreign investors in Australia's resources sector and convey this to India.

- 28.3Domestically, ensure ongoing complexities with the social licence for domestic thermal coal developments do not adversely impact investments and trade regarding metallurgical coal.

- 28.1Continue to advocate (through high-level visits, trade missions and Austrade) for investment opportunities in Australia