Appendix C: The International Nuclear Fuel Cycle

A characteristic of the nuclear fuel cycle is the international interdependence of facility operators and power utilities. It is unusual for a country to be entirely self-contained in the processing of uranium for civil use. Even in nuclear-weapon states, power utilities will often go to other countries seeking the most favourable terms for uranium processing and enrichment. It would not be unusual, for example, for a Japanese utility buying Australian uranium to have the uranium converted to uranium hexafluoride in Canada, enriched in France, fabricated into fuel in Japan and reprocessed in the United Kingdom.

The international flow of nuclear material means that nuclear materials are routinely mixed during processes such as conversion and enrichment, and as such cannot be separated by origin thereafter. Therefore, tracking of individual uranium atoms is impossible. Since nuclear material is fungible—that is, any given atom is the same as any other—a uranium exporter can ensure its exports do not contribute to military applications by applying safeguards obligations to the overall quantity of material it exports.

This practice of tracking quantities rather than atoms has led to the establishment of universal conventions for the industry, known as the principles of equivalence and proportionality. The equivalence principle provides that, where AONM loses its separate identity because of process characteristics (e.g. mixing), an equivalent quantity of that material is designated as AONM. These equivalent quantities may be derived by calculation, measurement or from operating plant parameters. The equivalence principle does not permit substitution by a lower quality material.

The proportionality principle provides that where AONM is mixed with other nuclear material and is then processed or irradiated, a corresponding proportion of the resulting material will be regarded as AONM.

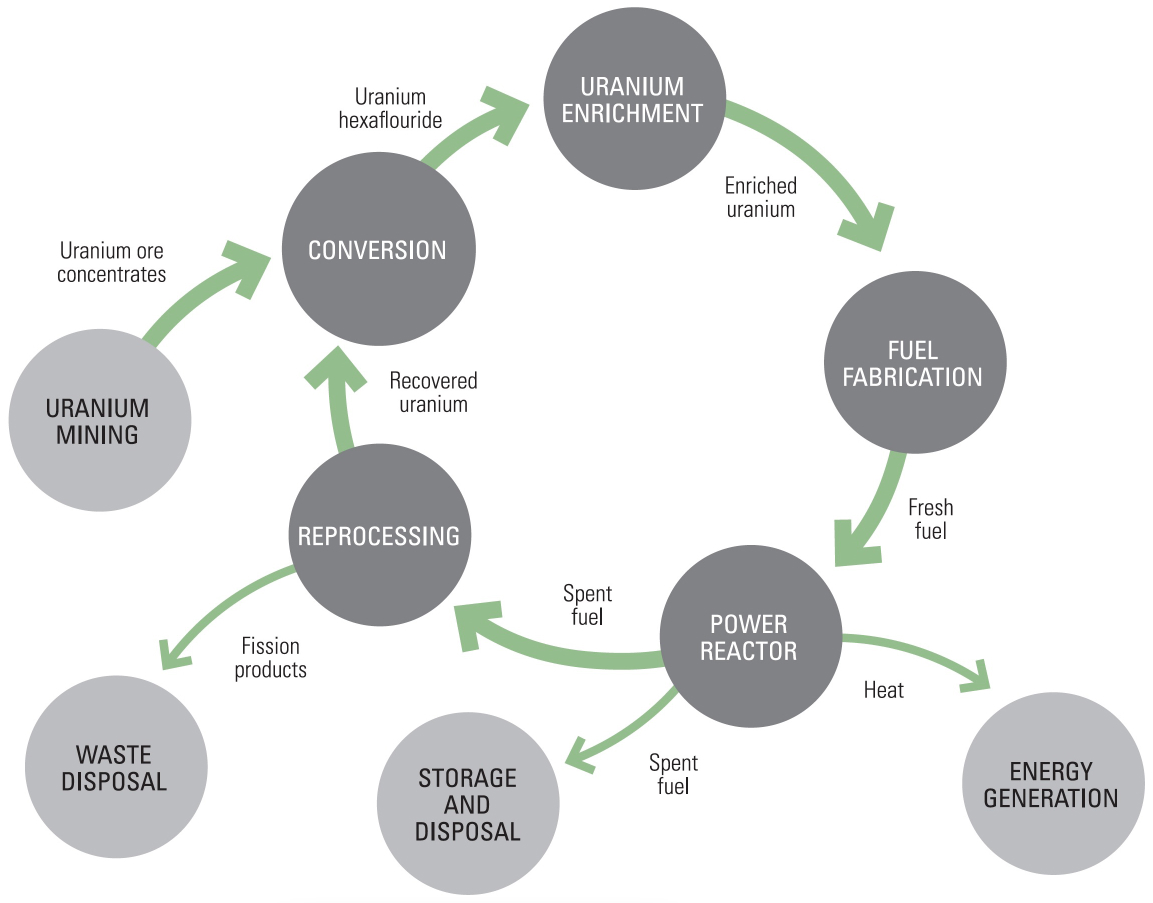

Figure 4: Civil Nuclear Fuel Cycle